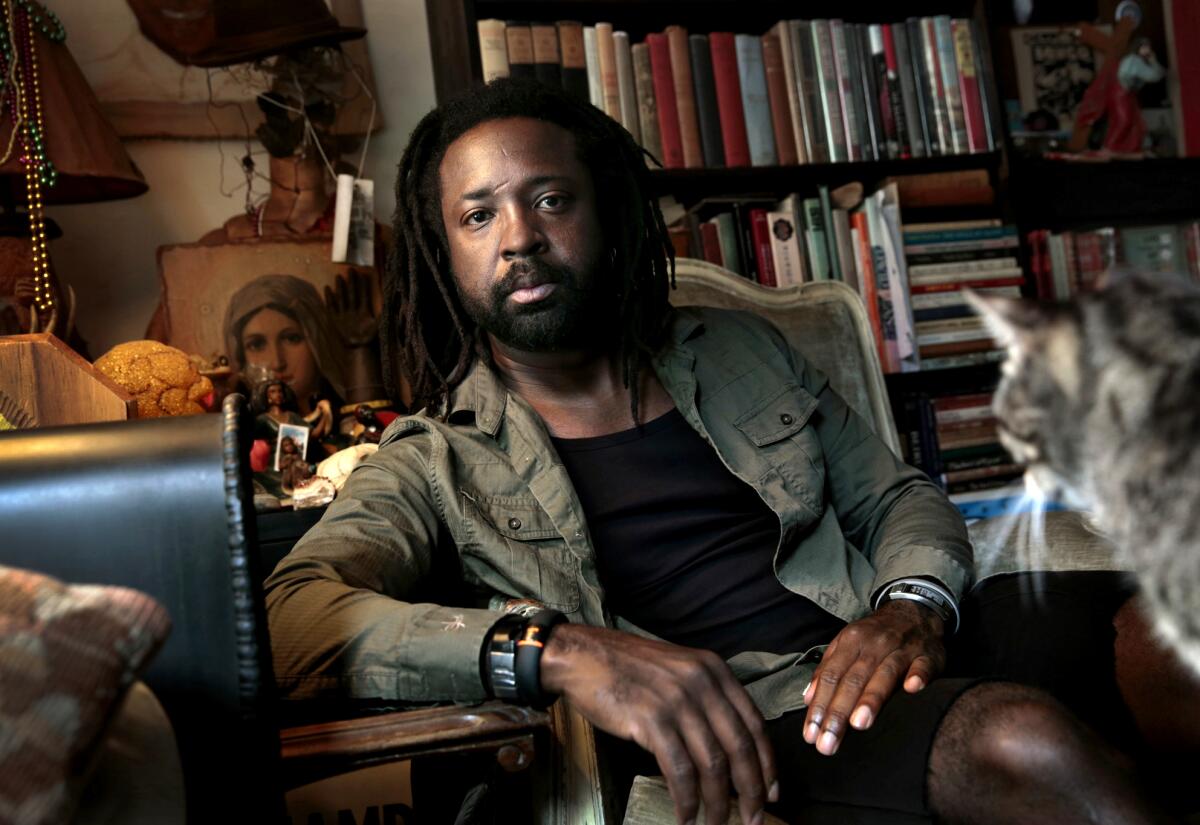

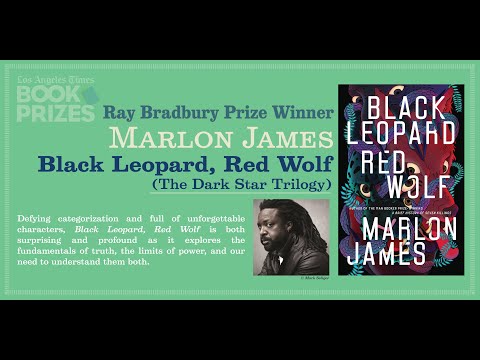

Dystopian fiction has always been real for Ray Bradbury prize winner Marlon James

If there’s a person you want to talk to in the midst of a pandemic, it’s probably a writer of speculative fiction — someone whose imagination is as wild and gnarly as the wild and gnarly times. Marlon James’ fourth novel, “Black Leopard, Red Wolf,” the winner of The Times’ inaugural Ray Bradbury Prize for Science Fiction, is his first foray into fantasy, but it retains the epic scope and kaleidoscopic quality familiar from his Booker Prize-winning novel, “A Brief History of Seven Killings” — a mind-expanding, brain-bending sensibility that asks for (and rewards) a reader’s focus and dedication.

Narrated by a man called Tracker, whose supernaturally keen nose has earned him work as a kind of bounty hunter, “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” is also a distinctly Jamesian entry into the fantasy canon. The book, the first in the planned Dark Star trilogy, is rooted in African mythology and animated by queer desire; it expands the genre it enters, asking us to continue to expand our reality and explore our relationship to the very idea of truth. Here’s our edited conversation about busting genre walls, dystopia as realism under the pandemic and the prospect of pop-culture world domination.

So we’ll start with what’s usually not a very loaded question: How are you?

All right as can be, I guess. I was reading about vigilantes in Maine blocking roads and forcing people they think are visitors to stay in their houses. I’m like, “Wow! We’re at ‘Walking Dead,’ and we don’t even have the zombies yet.”

You once said in an interview, about wanting to write speculative fiction: “We come to the end of what realism can express.” But it’s hard not to feel like life has become totally surreal.

It absolutely has, and it’s surprising how practical it is. The thing about dystopian fiction is, we focus on the horrors of it, but we never focus on the inevitability. I was watching “Handmaid’s Tale” last night, and every time I watch it I go, “But this could actually happen.” I come out of [the] evangelical church. I know the people working to make this happen!

I don’t think we can put that wall between us and dystopian fiction anymore. I don’t think we can read it the way we read historical fiction, where we are separated from it by reality.

It’s a great time to read the original speculative novel, Mary Shelley’s “The Last Man.” Funny enough, it was a plague — I was like, “Damn, girl. The original dystopian novel got it right!” And if there was ever a time to read “Moby Dick,” it’s now. I’m not talking the plague; I’m talking the way in which our government’s responding to it. We’re heading in this ridiculous direction. You want to understand the world, you need to get your “Moby Dick” on.

“Black Leopard, Red Wolf” brings African mythology into the white Western popular conscience. You did a lot of research for that book. What were some of the things that felt exciting and fresh to you?

One of the things that felt very exciting to me was the older attitudes towards queerness and otherness. I didn’t go looking for it, and I was quite shocked and pleased to find it. The whole idea of different genders and so on— I’m so glad people are accepting these other identities, particularly trans identities, but at the same time, y’all late. When you read these mythologies, some of these people have 14 genders!

The book also does a lot of work to make the reader question whether they can trust the story they’re reading. Why was that interesting to you?

The thing is that ancient audiences were far more discerning, and they brought far more skepticism and intelligence and wit to a story than we do. We bring almost nothing but our eyes. In a lot of African stories, for example, it’s a trickster that’s telling a story. So they make it already clear: I’m an unreliable narrator. The act of defining truth becomes something the reader has to find out.

Who are the writers who informed your work? Who’s in your speculative fiction canon?

I’ve read everybody. But in terms of the writers that made me think I want to do that — even though it took years to do it — lots of Nalo Hopkinson. The whole idea that the stories in my backyard could be a source of fantasy blew my mind. A lot of the fantasies for me wouldn’t be called fantasies. They’d probably be called more magical realist, but to me they’re fantasies. To me, Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon” is a magical realist novel.

It’s sometimes very hard for certain writers, writers of color and queer writers and so on, to write down on paper the story that’s in your head. The writers who will go on your permanent bookshelf tend to be the writers who redefine for you what is possible.

There’s also something that may not have seemed like a blessing to me when I was growing up, but I realize it now: I don’t have genre snobbery, because I couldn’t afford it. If you asked me, what kind of book did I read? Whatever book was next. God bless if I got a Virginia Woolf, but the next novel is gonna be Jackie Collins, who I adore. The only requirement I had for a book was that it was next.

Speaking of reading — you’re getting an award named after Ray Bradbury. Did you read him growing up? What did his work mean to you?

There’s so much of his work that was made into film and TV, so he was always a part of my pop culture universe. Ray Bradbury signifies to me a world of unabashed wonder, and the idea that the speculative story can still tell us as much about the human condition as any other kind of story.

Michael B. Jordan is working on adapting the Dark Star trilogy that begins with this novel. Will Marlon James one day be as big a piece of pop culture as Bradbury?

As a pop culture kid I’m like, “Hell yeah. Bring it on. I still have my ‘Star Wars’ action figures.” But also, part of me still doesn’t believe it, still finds it shocking that, in terms of storytelling, our time has come. “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” is not just an African story or black story. It’s a queer story. And the idea that that story’s time has come is surprising. I’m still having to pinch myself to believe it.

If what this means is that we’re opening up again, or widening the idea of what constitutes a story, then I’m all for it. My favorite thing now to watch is Korean zombie flicks — “The Kingdom” and “Last Train to Busan.” Just these stories that are familiar and foreign at the same time, which is what you want from any great story. Every great story is ultimately both things: totally familiar and absolutely foreign.

Romanoff is a writer and the author of several novels for young adults.

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Keren Taylor, Innovator's Award

2:04

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Namwali Serpell, Art Seidenbaum Award

1:51

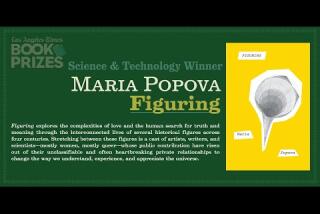

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Maria Popova, Science & Technology

3:09

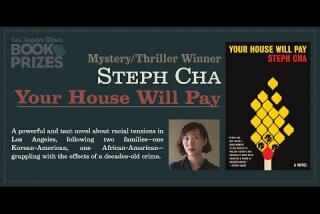

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Steph Cha, Mystery/Thriller

1:33

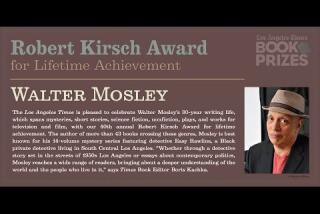

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Walter Mosley, Robert Kirsch Award for Lifetime Achievement

2:27

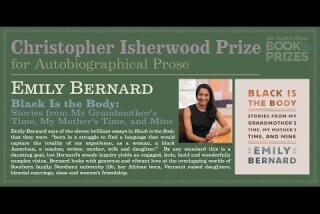

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Emily Bernard, Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiographical Prose

1:43

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, History

1:35

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Ben Lerner, Fiction

1:11

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Emily Bazelon, Current Interest

0:42

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Eleanor Davis, Graphic Novel/Comics

2:00

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.