Review: San Diego to San Francisco: An artful tale of walking California

Two vast private ranches lie just north of Santa Barbara, the path blocked by a locked gate and a guardhouse, with roads patrolled by men in pickups.

But Nick Neely, author of “Coast Range” and a poetry and nonfiction MFA grad, is in the middle of an epic quest: to walk the California Mission route from San Diego to San Francisco. He is following roughly the same 650-mile expedition undertaken by Father John Crespi and Captain Gaspar de Portolá in 1769.

The moon is nearly full along California’s Central Coast. Neely naps a bit, gulps an energy drink and hoists his pack just as the sun winks out. The going feels good as he walks the railroad tracks through the ranches. That is until he hits an 811-foot bridge over a deep and dark canyon. A train going 40 miles per hour could cover that distance in 14 seconds. Neely takes another step.

It’s a rare moment of tension in an otherwise well-mannered and thoughtful book, “Alta California,” which so often showcases Neely’s artful observations.

Such a walk might have felt aimless or undramatic, but whenever a reader’s attention might flag, Neely steers us back to the journals of Crespi, “arguably California’s first writer.” Constantly vibrating at the background of Neely’s journey is his single-minded focus on the original trek and the way he trespasses at night to stay on course.

He is able to deepen his journey by revisiting and considering the injustices at California’s early missions, the way Crespi and his ilk treated Natives, and then the legacy of the architecture and efforts to tame this wild and beautiful coast.

That ghostly 650 miles of the original trek, known as the El Camino Real, is a great way to talk about how much has changed, but it’s also an artful way for Neely to think critically about some of our founding mythologies.

Imagine, he insists, the terror of a Native American woman encountering pale skin for the first time, wondering if it is an anomaly or a disease, and then feeling perplexed at the newcomers’ baptism rituals. “They gesture that they want to trickle water over her daughter,” he writes. “That this will send her to the sky. In this both tender and invasive moment, California begins to tip. The land itself goes through a small rite that honors one culture at the expense of another.”

Neely also is an excellent field guide. For example, he doesn’t just camp under a big tree, but notes that under its canopy the air is cooler, “a palpable microclimate, as if the trees were generating their own breeze. A sycamore,” he adds, “is a phreatophyte or ‘well plant’ with deep roots to tap into what little water there is far below.” He spies a roadrunner, or “chaparral bird,” which he says is a “warrior bird that has retained its dinosaur spirit. It will hide among flowers,” Neely writes, “to snatch a hummingbird out of the air.”

He is, moreover, a thoughtful observer of people in public, the way we live and the way we work, and the decisions we’ve made about how to manage our land, the so-called “built California” he’s spending months traversing. After all, Neely’s project isn’t to walk the Pacific Crest Trail — the kind of terrain he calls “an escape from our reality and layers of history” — but a webbing of official paths, railroad crossings, private property and roadsides. Or, in Neely’s words, “where we actually live.”

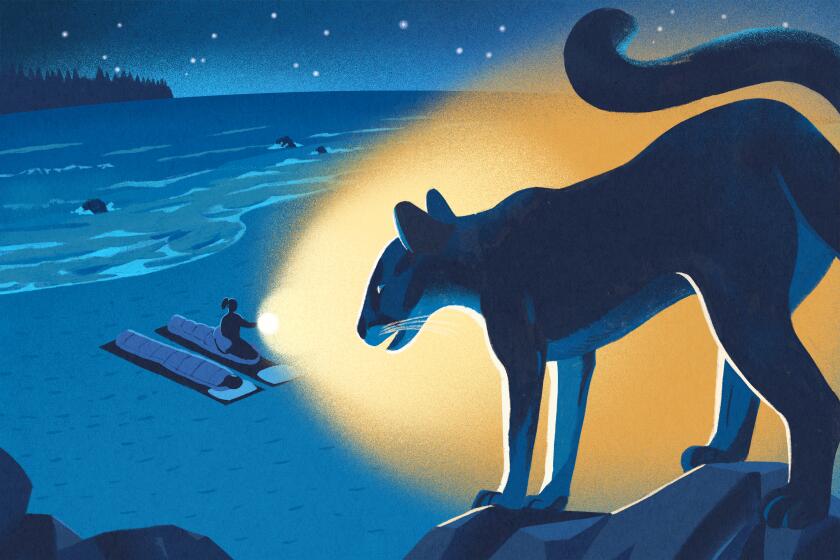

Neely waxes poetic about the browns of Southern California: “The hills the color of a cougar … Dirty blond and rosy brown, invasive khaki, coffee with milk, the rusty umber of California buckwheat, potato skin to the horizon.”

Elsewhere: “Brown pelicans soared low, classic, in formation until each peeled off from their V, one by one,” he writes. “Parents,” he continues, “were doing their honest best to defend their kid’s skin with mist of spray-on sunscreen ... On Oceanside pier, which stretches nearly two thousand feet into the Pacific, a fisher in a hoodie sat on a pail eating a dripping mango as he waited for sand shark.”

This fine, enjoyable book doesn’t necessarily offer some grand new theory, other than the immensely rewarding experience of undertaking a difficult journey, and doing so with the distant past in mind. When our guide reaches the end, greeted by his family, a reader might savor a touching detail: His mom lights candles to guide his final steps into the family’s Bay Area driveway.

Which shoes should you wear on a trip like this? “What you’re used to is what is comfortable,” Neely says.

By Nick Neely

Counterpoint: 432 pages, $26

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.