‘The Boy and the Heron’ composer wants you to feel the movie, not search for meaning

The musical theme for Hayao Miyazaki’s new, and likely final, film is a question — just like the film’s original Japanese title. “How Do You Live?” was (regrettably) renamed “The Boy and the Heron” for English audiences, but no matter. The hand-drawn masterwork from the 82-year-old animation giant spills over with beautiful and heart-aching questions.

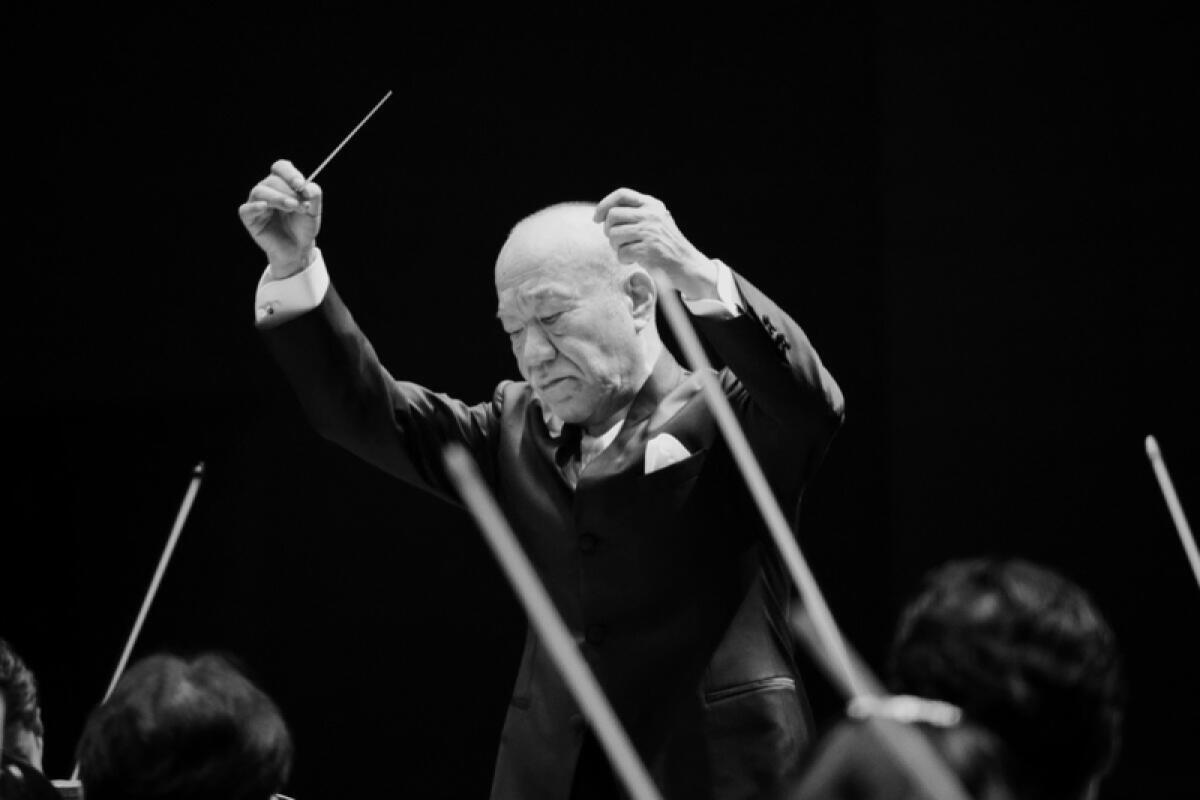

Joe Hisaishi, the veteran composer of every Miyazaki feature since 1984, responded to that original name and gave his theme the English title “Ask Me Why.” Through a translator, Hisaishi said he did that “to show that we’re constantly asking ourselves questions and asking ourselves the meanings of things.”

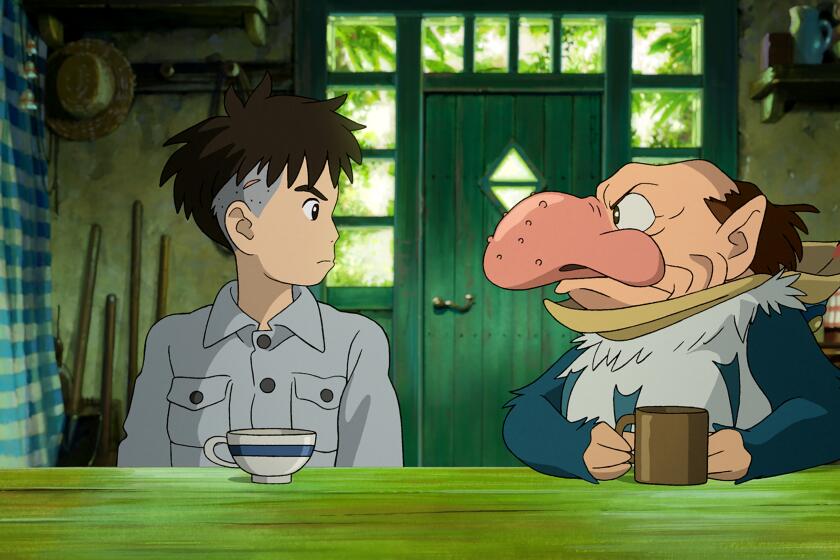

It’s a bright and gentle song for piano and strings, almost childlike in its purity, and it repeats at key moments in this film about a boy, Mahito, who loses his mother in a hospital fire and enters an enchanted tower in the country with the quixotic hope of finding her again. It’s a theme for a young boy’s search for love and meaning, as told by these two great artists on the reflective end of life, simultaneously simple and profound.

And personal. Because much of the story was taken from Miyazaki’s own life, his composer felt he needed to approach it delicately and with his own hands.

In a tribute, director Guillermo del Toro says of the animation master’s films, “They are paradoxical because he understands that beauty cannot exist without horror, and delicacy cannot exist without brutality.”

“I decided right at the start that this film probably would not be good to have a full orchestra playing the whole time and that I would play the piano,” Hisaishi said. “It would be a chance for me to move myself close to what Miyazaki had intended.”

The film is divided into two halves: the first a surprisingly grounded drama of Mahito adjusting to life at his new country house, feeling lonely and being taunted by a curious heron. Once Mahito enters the tower — a wonderland of talking birds, unborn souls and the boy’s godlike granduncle — the score grows larger and stranger, with quirky tuned percussion, electronic effects, chorus and reverberant, cosmic orchestration.

Hisaishi, who has been hailed as “the Japanese John Williams,” has always been a hard composer to pin down. His 11 scores for Miyazaki — from “My Neighbor Totoro” to “Spirited Away” to “The Wind Rises” — are united in their playfulness, sense of wonder and penchant for poppy melody.

But each individual score is an eclectic contradiction unto itself, transforming — like one of Miyazaki’s oozing supernatural creatures — from electronic minimalism one moment, to a chamber circus, to a grand classical sweep, to a children’s song. Like the stories they accompany, his scores are eclectic and unpredictable and seem to be broadcasting from an uncanny world while still somehow providing the comfort of an old waltz or familiar lullaby.

Ten years after ‘The Wind Rises,’ the world’s greatest living animator returns with a hauntingly personal story of grief, loss and perseverance.

The two artists make for an interesting team. Miyazaki is 10 years older, and they’re not close friends.

“We don’t go out to dinner together, and I don’t meet him in personal settings,” Hisaishi said. “Only working on the films are we connected. So maybe that’s the secret to having continued for this long.”

Their first collaboration, in 1984, was “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.” Miyazaki had pasted storyboards on a wall, and as he was describing the film — set in a far-off future plagued by climate and war crises — he suddenly jumped up on a chair to point to different scenes and explain what they were about.

“So I thought he was kind of an interesting, strange person,” Hisaishi recalled, laughing.

They worked in the same way over the decades, with Hisaishi coming on during the storyboard phase and developing his score in tandem with the animation. But on the newest film, Miyazaki, for the first time, didn’t want his composer to see the movie until it was almost completely finished.

“I think what that really meant was that Miyazaki wanted to tell the story all in pictures, basically,” Hisaishi said.

On all previous films, the composer tried to come up with a strong central melody and derive a score from that. But for “The Boy and the Heron,” he wanted to write something more minimalistic, built on repeating patterns.

“I did not want to describe emotions or scenes through music,” he said. “I wanted to be at a certain distance from the story and the characters, and I wanted to be in between the actual story and what we see on the screen, and the viewers, in terms of writing the music.”

In other words ... he wanted to ask questions.

Hisaishi recently heard from minimalist American composer Terry Riley, who saw the film in Japan without subtitles. Riley said he couldn’t really understand the film, but he could feel it. That’s what Hisaishi would prescribe to anyone.

“I would suggest to not search for real meaning in the film but to just let yourself feel it. I think that will end up being a much happier experience,” he said.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.