For Luca Guadagnino, it’s not about the cannibalism, but human desire and connection

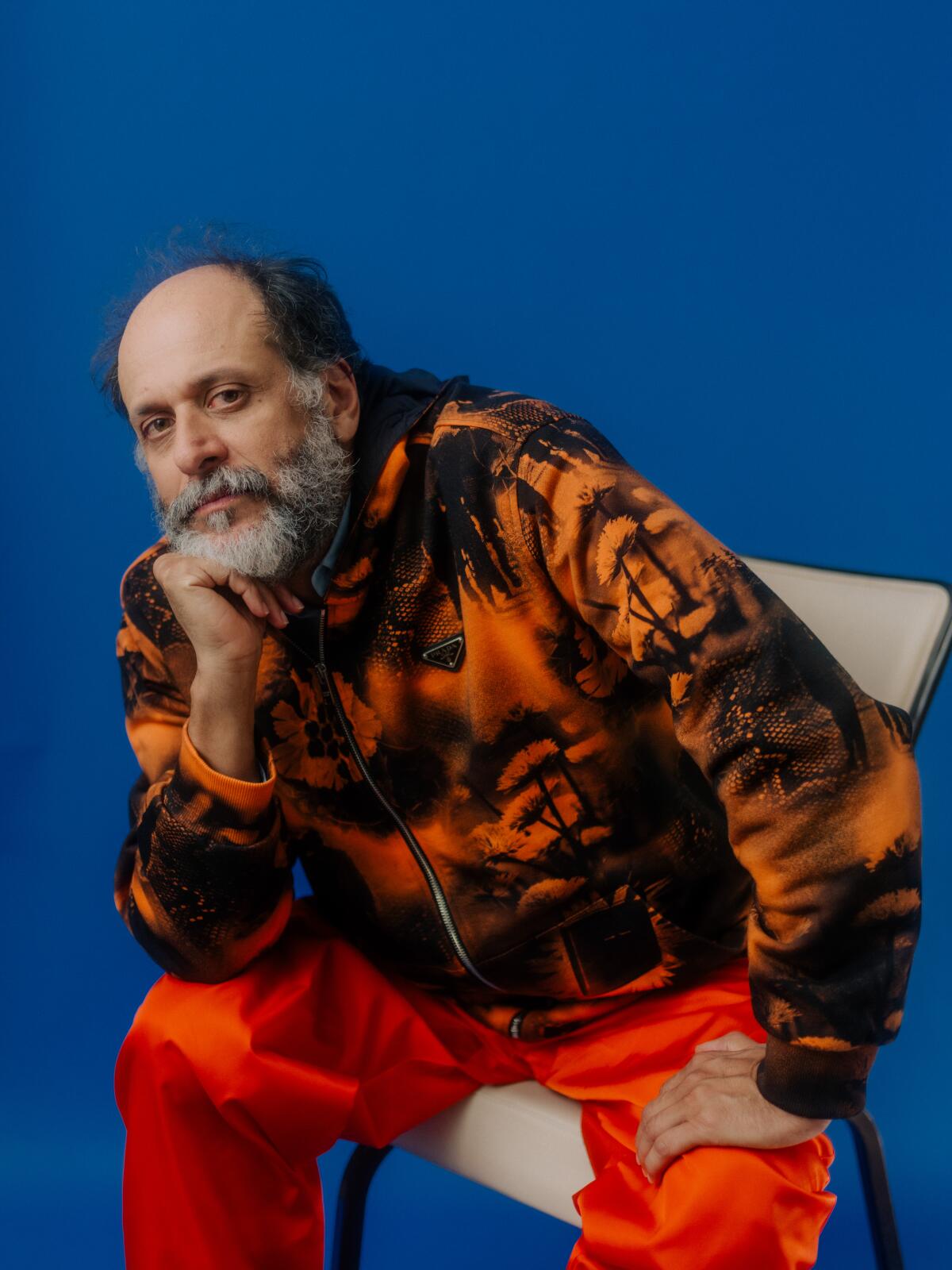

When Luca Guadagnino encountered the isolated, searching outcasts at the heart of “Bones and All” in Dave Kajganich’s screenplay from Camille DeAngelis’ novel, the Italian filmmaker was reminded of a quote from philosopher György Lukács he’d long cherished. “It said, more or less, that to be a human being means to be alone,” recalls Guadagnino. “At the end of the day, this is about people being alone in the void, the void of life, of experience. There is something almost fairy-tale-ish about it.”

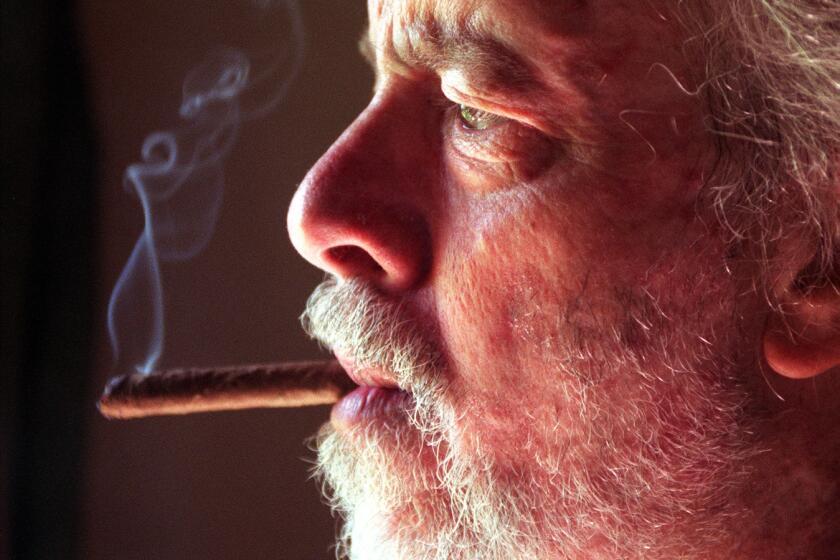

Nursing a cup of tea on the patio of a Beverly Hills hotel, Guadagnino likens his movie’s protagonist, Maren, a teenager on the run played by Taylor Russell, to Red Riding Hood, “left alone, not knowing why she has been left alone, and having to discover herself while discovering the larger world, the woods of America.”

And yet Maren is also not unlike the wolf in that fairy tale, in that within her is a terrifying appetite for eating people. It’s to this emotionally attuned director’s credit, however, that in the 1980s-set “Bones and All” — built around a road trip across America — he saw something not horror-driven in its hunger and fear, but quietly human. “As always with the surprises that come with life, you could make a very tender movie, a very gentle fable about the impossibility of one’s nature, and make that the story of people who are eaters. Cannibals.”

Maren and Lee, played by Timothée Chalamet, are outlaw lovers in a movie lineage that goes back to “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Badlands,” and Guadagnino thinks our attraction to such stories has to do with love itself. “We are outlaws the moment we are driven by our desires,” he says. “Loving someone is a dangerous thing. Love is scandal.”

In this case, just add blood, something Guadagnino is not unfamiliar with, from its brief appearance in his “Call Me By Your Name” (a humiliating nosebleed) to its operatic quantities in “Suspiria.” This time, though, it was about its everyday reality for his characters, as in one post-feast scene. “They’re completely soaked in blood, because that’s what they’ve been doing, and they have this conversation about who they are,” says Guadagnino. “It’s very mundane, and very candid.”

‘Waves’ duo Kelvin Harrison Jr. and Taylor Russell on the heartrending family drama of the year

What was new for Guadagnino was shooting in America. Though he says his own imagery was “forged” in American cinema, art and music videos, he understood the baggage accompanying European directors telling stories set in the States. He didn’t want to fetishize America as an outsider, or rain judgment on it. “It took me turning 50 to feel the maturity I needed to find an intimacy to the landscape, not a distance,” he says. “That arrogance of ‘I’m going to show you who you are,’ it’s not interesting to me.”

The journey of an Italian in America also characterizes the documentary Guadagnino released this year, “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams,” an interview-rich chronicle of the legendary shoe designer Salvatore Ferragamo’s conquering of silent-era Hollywood and, subsequently, out of Florence, the fashion world. What Guadagnino found most fascinating was how Ferragamo’s time in America educated him in invention.

“[Martin] Scorsese talks about it in the movie, the reinvention of self in America,” says Guadagnino. “[Ferragamo] thought he had to give the dream of Italy to his American clients.” Relocating to Florence was as much about its selling point as a Renaissance capital, the director says. “He could create it as an imaginary world to trade his idea of Italy. He invented ‘Made in Italy.’ Of course, it was about the quality of the craft, but he was inventing worlds all the time through the idea of craft. A complete and absolute visionary.”

Guadagnino is no slouch himself with craft. Needing “Bones and All” to not just evoke its time period but feel ’80s-made, he shot on 35-millimeter, with its precious canvas of grain and depth, instead of with digital cameras, which favor flat hyper-reality. “Cinema, being organic and working on the level of light, not digital data, is about contradiction,” Guadagnino says. “It’s about the space of light and dark, the texture of things. The idea of sameness, of homogenization, comes with digital. Because everything looks the same. It avoids the possibility of reality, reality being the battlefield where we have to fight for our ideas.”

With his sensorial approach to character studies, often favoring tales set in previous eras, is Guadagnino a filmmaker from another time trapped in the 21st century? He takes the question as a compliment. “I don’t know, I don’t know,” he says. “I hope I can talk to the anxieties of nowadays with my work, and I believe that the form cinema reached between the ’50s and ’70s is quite unparalleled. I’m not nostalgic, though. I’m not one of those who says cinema is dead.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.