With 90 different costumes, designer Catherine Martin kept Elvis flashy and sexy

It’s no easy feat humanizing a global icon such as Elvis Presley. Consider, he still has impersonators officiating at endless kitschy Las Vegas weddings 25 years after his death.

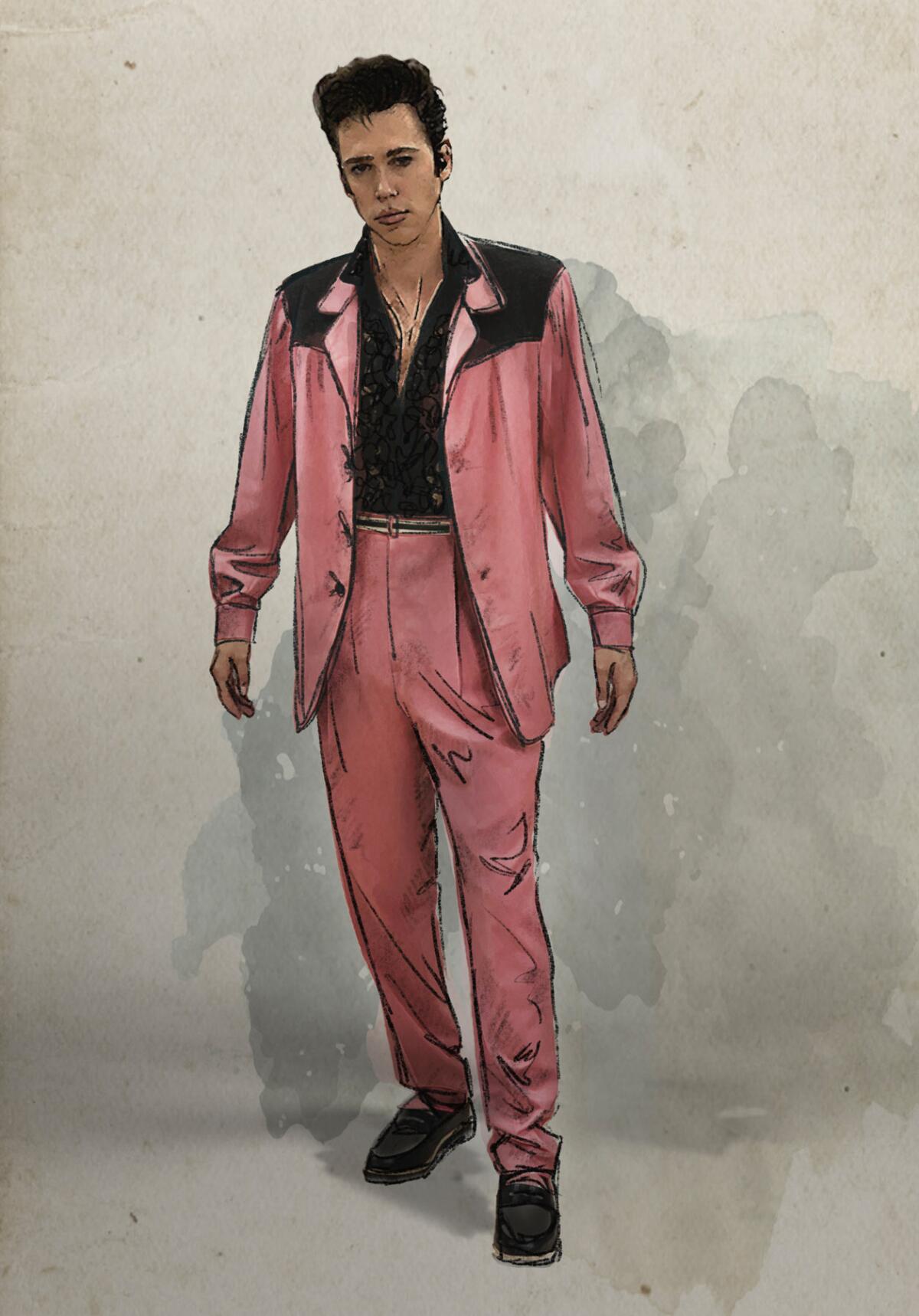

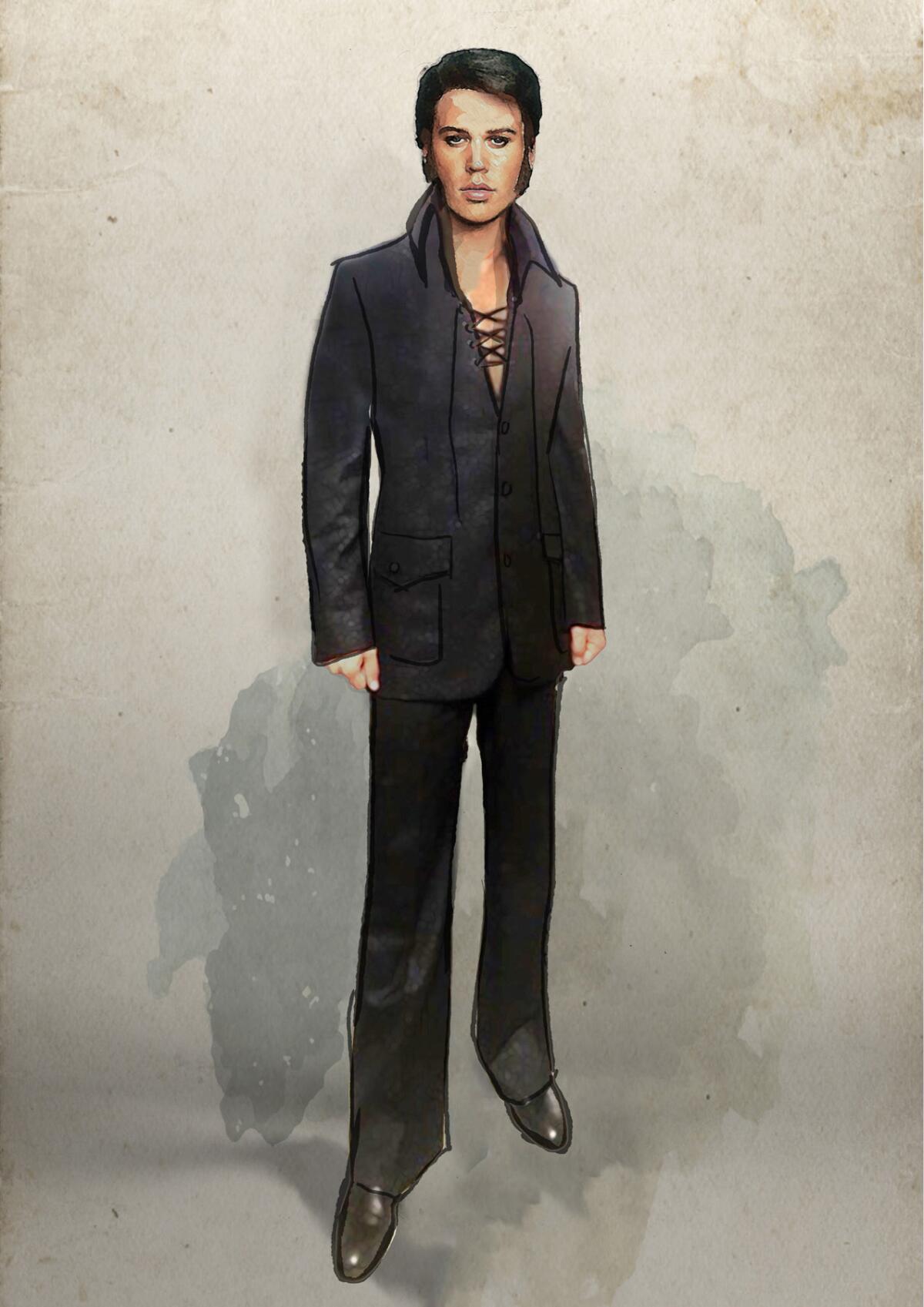

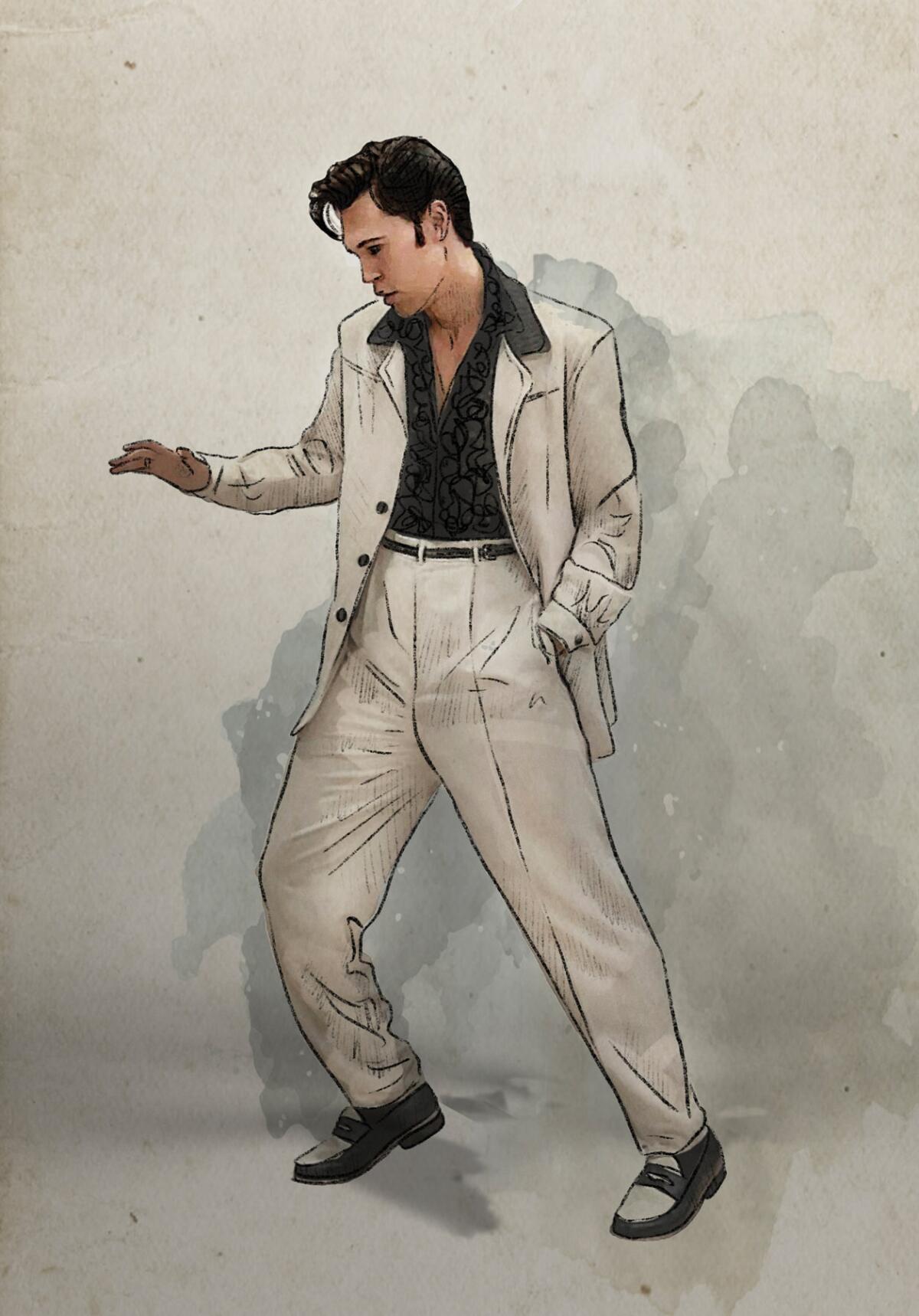

Part of that humanizing fell to costume designer Catherine Martin, who showcased in the summer-release “Elvis” just how sartorially stylish this young Southern boy was, how original and rebellious he appeared in what he chose to wear and perform in.

The riotous and colorful film stars Austin Butler as Presley, Olivia DeJonge as his wife Priscilla, and Tom Hanks as his manager Colonel Tom Parker. It’s directed and co-written by Martin’s husband and longtime collaborator, Baz Luhrmann. The couple live in Australia.

Martin excuses herself at the beginning of our transatlantic call: It’s Luhrmann, and he needs help trying to rendezvous with his daughter in Sydney. The conversation is so normal and soft, which belies the over-the-top flamboyance of the film. “OK, bye then, love you,” says Martin, who then returns to the topic of the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Baz Luhrmann’s erotically charged biopic “Elvis” doesn’t just reinvigorate the Presley myth, it resurrects the King and makes him relevant again.

Elvis truly was his own stylist, as he lived long before fashion stylists even existed. Ponder that amazing feat: conquering the world not just with his music but with his look — the one he created on his own as a working-class Memphis teenage boy.

Black performers always had a strong visual sense, and someone like Frank Sinatra stayed within the sartorial norms. But Elvis, for a white performer, said, “I am going to lead the charge.” Whether that was because he suffered from stage fright and needed to create these larger-than-life personas to hide behind and exploit, he really understood, profoundly, the creation of a stage persona.

And so young …

Yes, so young. He created these looks himself. He started fashion. He collected influences from all different kinds of places, and his look was truly his. He had noble collaborators — Lansky Bros. [clothing store] or working with [costume designer] Bill Belew when they developed that high Napoleon collar and the jumpsuit. Even then, Elvis had the ability to say, “Yes that is a good idea, let’s go with that.” And then it became his calling card.

And we forget looking back 70-odd years how dangerous and threatening his whole look first appeared. It might not look so in 2022, but in the 1950s Jim Crow South, it certainly was. And his clothes had much to do with that, not just how he wore them.

That was something Baz really drilled into us. He was adamant Elvis not become a comfortable, sartorially easy excursion into costume. It had to be really clear that he was challenging so many 1950s mores and was threatening to the status quo. Baz cut the tone: We have to work within the historical confines of the 1950s and the vernacular of Elvis’ wardrobe, but we know to select things within that vernacular that showcase that sexuality and that rebellion.

Austin had 90 costumes. What kind of fitting sessions did you have? How involved was he in the costumes?

Involved? I think he had post-traumatic stress disorder! We spent hours and hours in the fitting room together. He always wanted to have his fitting on his rehearsal days, because he found it to be very exhausting. Sometimes we were trying on three different suits that could take hours, and I don’t know how many jumpsuits. He’d do it after a full eight- to 10-hour day of rehearsal. He’d come in anyway and it’s one-to-four hours working through all the clothes. Costumes/clothes are just that when they’re on the hanger in the dressing room. It’s the incredible alchemy between the performer and the garment that creates the magic. Austin has that incredible alchemy.

It’s interesting how Elvis always acted quite feminine and flamboyant, but he always read strictly masculine, unlike Liberace or Elton John. I don’t know what that is — but Austin got it perfect.

Yes. I think it’s what is so sexy. The contrast — between something flamboyant and possibly gender-challenging to the eye, but the fundamental masculinity of the performer — I think it’s profoundly attractive. I haven’t quite been able to analyze what that is. I see it very much in Harry Styles, too, though he takes it much further, and Elvis was a half-century before.

Colonel Tom Parker. You referred to him as an “oddball disrupter.” That heinous Christmas sweater showcased it perfectly. Didn’t it bug Elvis?

It definitely bothered him. That was one of the things that unnerved Elvis. But I think Parker did it to unnerve people, to put people on their back foot. It’s so funny with Tom, because in the film he’d go through 5½ hours of prosthetics every morning. Of course, I’ve seen him without makeup lots of times, and even if I came in at 5 a.m., he’d still have started. With all that I’d actually forgotten sometimes he’s Tom Hanks and not Colonel Parker. Just seeing Tom dressed in Parker’s clothes every day, it was kind of a pleasure doing so many terrible clothes. And the Colonel owned many more things that were worse!

I also read somewhere the Colonel wanted to copyright the jumpsuit.

Yes, he did! But Bill Belew of NBC, who worked with Elvis on it during his TV special, also used it for the Osmonds and the Jacksons and said, “Forget it. You can’t copyright a jumpsuit.” And when you think about it, that jumpsuit with the high collar, it truly is a remarkable moment in costume history.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.