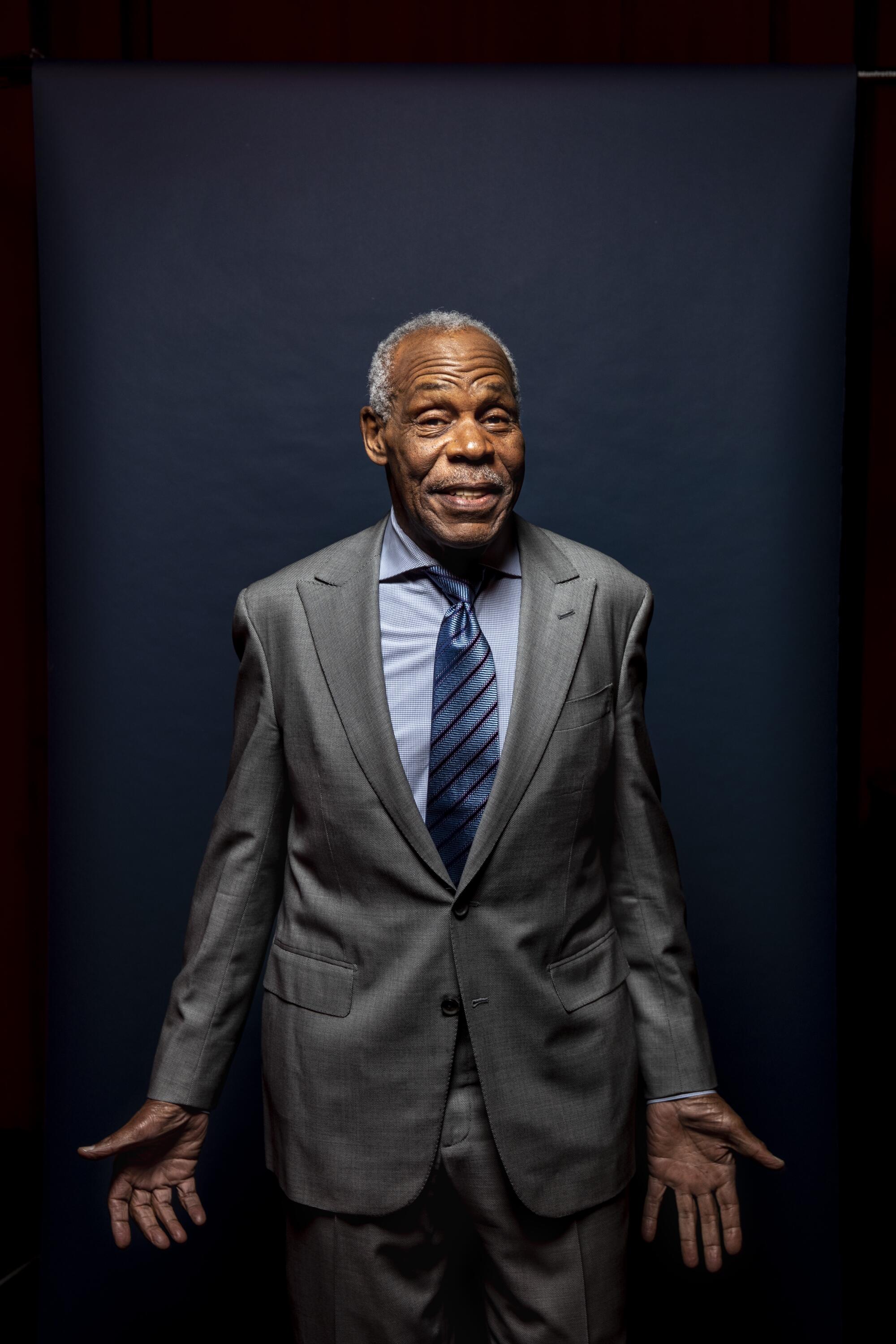

Danny Glover often manifests at the front door, either a stranger or an old friend — an angel or a devil. Hat in hand, he knocks on a widowed mother’s door in “Places in the Heart” and ends up becoming part of the family. He visits a long-lost friend in “Beloved,” a survivor of the same brutal trauma, bringing love. In “To Sleep With Anger,” he shows up at his brother’s L.A. house grinning and ingratiating — Satan in a suit and a smile.

In real life, Glover has been a friend and angel for countless causes in the name of justice and liberation — from the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa to communities exiting the prison system in Northern California. He’s winning his first Academy Award soon, not for any performance but for who he is as a human, this year’s recipient of the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.

“Now everybody says ‘I’m an activist,’” said Alfre Woodard, who will present her friend and frequent co-star with the honor at the Governors Awards. Glover was an activist “before it had a name that way in the zeitgeist. You know, he just said, ‘Hey, have you heard about this? Have you heard about that? You know who’s in jail right now in Zimbabwe?’ He always had his finger on the pulse.”

Glover has served on numerous boards, acted as a goodwill ambassador for the U.N. Development Program and a UNICEF ambassador and traveled the world to places of conflict or inequality — offering not just his money and famous name but his time and sweat, too.

“It was just an act of the universe blessing everybody when his star started to rise,” said Woodard, “because that just meant he had the ability to affect more people, and to effect more change and effect more justice.”

Glover, 75, inherited his heart from his parents, who were postal workers in San Francisco and members of the postal union. He watched his parents join the civil rights movement, and as a teenager with a paper route he paid attention to news coming out of the South about the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and activists such as Bob Moses, who later became a friend.

“I remember when [Moses] came out there in my senior year in high school and spoke at Stanford University, recruiting students to go down for Freedom Summer,” said Glover. That’s when he and his peers began asking the question: “How did we see another world?”

As a student at San Francisco State University, he joined a coalition of Black, Latinx and Asian students for a months-long Third World Liberation Front strike and was arrested for his cause. He got involved in local community development and tutoring, catching a lifelong love for “grassroots, democratic action by ordinary citizens ... taking responsibility for their own rescue.”

Glover never left his roots — literally; he still lives 12 blocks from the house where he grew up in Haight-Ashbury. It breaks his heart to see the undoing of the good work he and others accomplished back in the 1960s and to walk past homeless people every day, including people he knows.

“Sometimes they don’t ask me for any money,” he said. “They’re just saying: ‘You see us. You acknowledge our presence.’ They’re right around the corner from my house. And I don’t walk around them.”

Glover may have been forged in the “political cauldron” of 1960s San Francisco, Woodard said, “but from the very beginning he connected it to international communities — not thinking internationally, but he’d say, ‘You know what? Same struggle is going on over in Mozambique,’ or wherever he was talking about. He’s always had a worldview, but he thought of the world as his local community.”

While working in city government out of college, he took an interest in acting, inspired by the works of South African playwright Athol Fugard.

“Black art itself has always been an attempt to be able to elevate our story, to enrich our story,” said Glover, who honed his craft on the stage and by 1981 was booking parts on TV and soon the movies. His performance as Moze in “Places in the Heart,” a kind cotton farmer who helps a white widow in rural Texas only to be attacked by the Ku Klux Klan, earned him accolades and launched his Hollywood career.

“He was so young and gorgeous and vibrant,” said his co-star Sally Field. “And to me, to have what happens to Moze in the film, to that beautiful young man, was much more heartbreaking.”

While filming in Waxahachie, Texas, in 1984, Field remembered Glover saying, even then, there were local bars he didn’t feel safe going to with the other cast members.

The actor saw his Southern ancestors in the role, and he dedicated it to his mother — who died before she saw the film. “I know my mom is smiling,” he said.

Glover has played good cops — most famously in the blockbuster “Lethal Weapon” series — and bad cops, as he did in Peter Weir’s “Witness.” He’s been everything from an embittered baseball coach who adopts two foster children in “Angels in the Outfield,” to a sinister wife-beater in “The Color Purple.”

When his grandmother saw that 1985 Steven Spielberg film, she said: “I’m gonna get a switch after that boy!” he said with his hearty laugh.

Glover used the cachet of “Lethal Weapon” to get social dramas produced — such as “The Saint of Fort Washington,” where he played a homeless man in New York. He also made sure to shine a light on apartheid and other real-world issues in the “Lethal” films.

“They’re sort of silly in a lot of ways, these films,” said his “Lethal” partner, Mel Gibson, who’s currently developing another entry with a part for Glover. “But at the same time, there’s always a little something in them that addresses some kind of issue, where there’s an imbalance that calls for a little equilibrium.

“I just have a tremendous amount of admiration for the guy,” Gibson added, “because he puts his money where his mouth is. And he’s tough. He’s consistent with whatever he does.”

One of Glover’s most acclaimed performances was in Charles Burnett’s “To Sleep With Anger” (1990), a low-budget indie that struggled for financing until the actor came aboard and lent it his star power. Burnett initially offered him the part of one of the young men in the story, but Glover asked if he could play Harry, the old-timer who drifts into town and starts causing trouble.

“It’s supposed to be an ambiguous kind of a role,” said Burnett, “because he’s not definitely evil, as such. It’s subject to one’s take on it. Because you never see him do anything bad, physically — you know, it’s more a rumor you hear. And he comes out and he says very honestly, up front, ‘You don’t know who I am.’ Everything he does has an element of truth to it.”

Glover doesn’t regret taking a single role. “Beloved” is the most important film he ever made, he said, “because it brings a different kind of care to pain, and historic pain, and what happens to people after 250 years of bondage. How do they have to fight through the idea of identity? How do they restore their own value?”

More recently, Glover has been in films set in his hometown — including “Sorry to Bother You” and “The Last Black Man in San Francisco.” Jonathan Majors played his grandson in the latter and marveled at how Glover “models vulnerability and empathy. He has the ability to make you believe, instantly. And not all actors have that. A technique that’s invisible.”

Glover never left San Francisco, even as his star rose in Hollywood. He bought his current house in 1975 for $62,500 when he was working for the city on a salary of $21,000. He shakes his head thinking about how so many of his neighbors and even family members have been squeezed out.

“It’s really difficult in the city, but I love the city,” he said. “The tragedy, I think, of certainly the system, is that housing becomes a commodity, and because it becomes a commodity, then people are pushed to the side.”

Glover reminisced about his childhood and about his grandparents and his father (“best friend I ever had”) and his four siblings, two of whom have died. Woodard believes his humanitarianism was bred at home.

“When he would talk about his mom, he would get a smile on his face, and he would always touch his chest,” said Woodard. “He had that compassion, and the attention to detail in terms of seeing a person and seeing a person’s need.”

In the course of an hour, Glover flitted from talking about voting rights, math literacy, job security, mass incarceration and a half dozen other issues close to his heart, from injustices in his backyard to those in Africa and Palestine.

“But one of the things that is consistent, I think, is trying to have a vision of a better world, and a different world,” he said. “The question is, for us, what role do we play? Which side are we on in that change? And I think part of my understanding of that would have been the same whether I was an actor or not.”

Still, he added, “artists are not absent from that discourse. And the audiences aren’t absent. They want to know more, they want to learn more, they want to see the possibility of change — certainly the change within a character, but the possible changes without.”

What hasn’t changed for Glover is his optimism and humility, which others help him maintain. He still sees some of the guys he used to play-fight with as a kid: “I get a kick out of it, man. They’ll say, ‘You may have done some movies, but you still a chump!’”

And he laughs that Danny Glover laugh.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.