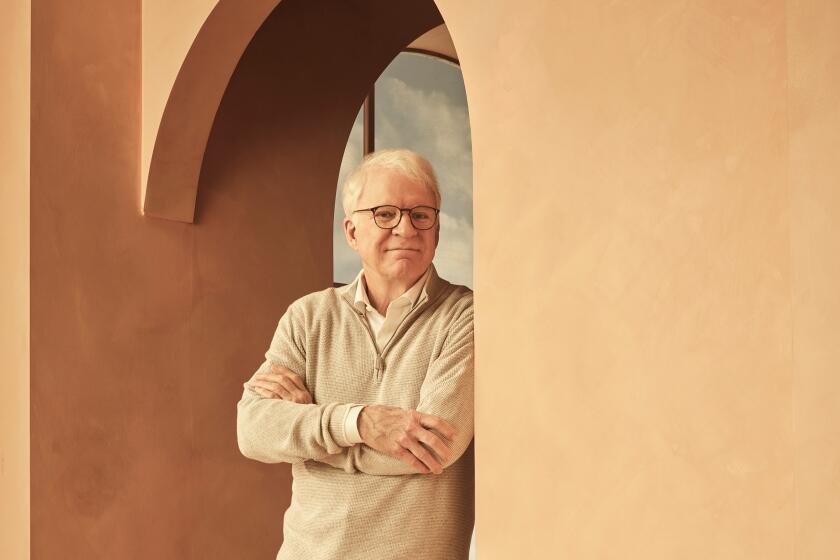

He’s dressed Lin-Manuel Miranda, Oprah Winfrey and even Jesus Christ in a way, but Paul Tazewell took on his largest ever project when he signed on as costume designer for director Steven Spielberg’s massive movie remake of “West Side Story.”

For nearly 30 years, Tazewell has accumulated dozens of costume design credits and awards for theater, film and television, including a Tony for “Hamilton” and an Emmy for “The Wiz Live,” along with nominations for “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert!” He’s not just a wiz at colorful musicals; Tazewell also costumed Winfrey for HBO’s drama “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.”

In “West Side Story,” Tazewell builds a visual story that contrasts hope and hardship amid the physical and personal wreckage wrought when a section of Manhattan’s West Side was cleared to build Lincoln Center. Mere minutes into the first act, the warring Jets and Sharks gangs are pelting one another with buckets of paint, cans of trash and a truckload of watermelons. That’s the first clue that this “West Side Story” is getting real, real quick.

“Steve was after an authentic and plausible version of ‘West Side Story’ and our reflection of 1957 New York City,” Tazewell said. “Space needs to be made if you are going to have that kind of gentrification. The ramifications for those communities can be very dire.” It shows in the clothes.

Virtually every element in this more ominous and visceral “West Side Story” is doing heavy lifting to correct the historical record that had, for example, cast white actors as Puerto Rican characters. Costumes are more often drenched in sweat and grime, their seams shredded from wear and, in Tazewell’s hands, conceived to capture immigrant pride and social strife.

“Some of my original inspiration visually was Bruce Davidson’s photos of gangs in the 1950s in New York and also in Brooklyn. He embedded himself within those gangs,” Tazewell said. Davidson spent years photographing East Harlem, and his stark black-and-white imagery shares the film’s somber mood and exacting detail.

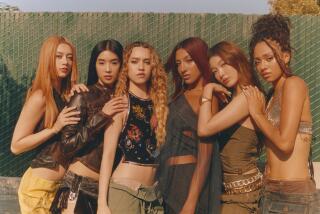

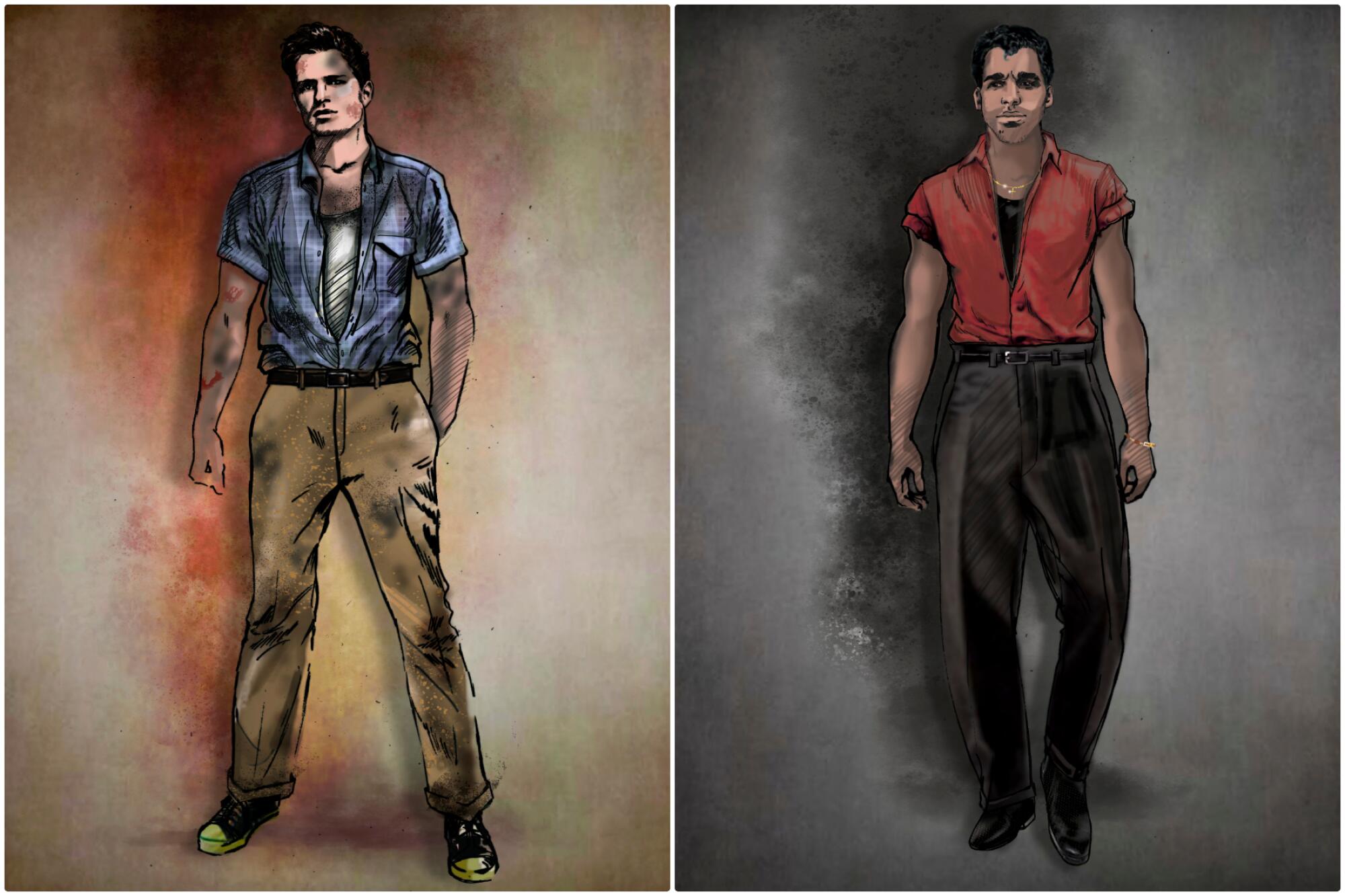

Tazewell also enhanced the differences between the Jets and the Sharks. He chose distinct color palettes to help audiences track the different groups whether they were dancing in the school gym or fighting in the street — a sort of ’50s version of the Crips and Bloods. He assigned cool hues of blue, teal and gray for the Jets. For the Sharks, it’s warm golden tones of red, yellow, orange and brown and, often, tropical prints that reflect their Puerto Rican heritage.

“The dynamic of those two worlds coming together and how they clash was important to the storyline,” Tazewell said. The gymnasium dance scene divides visually but also psychologically.

“I was thinking of the contrast in aspiration for the different communities,” he explained. “With the Latinx community, they are dressing more consciously fashion-forward than the Jets are. The Sharks have to try harder. That is part of feeling like an outsider in America. You try harder to represent yourself [to be] as put together as possible, so you garner respect.” That connection to clothing and dressing well was familiar to the designer, who said he also absorbed those lessons from his family of African American migrants from the South.

The Jets, who claim white European heritage, “are more comfortable and casual in how they dress. They are the only group I dressed in denim and jeans. It’s an icon of America.” The Jets women favor fashionable, sleek silhouettes that needed “very tricky costume geometry” to open for dancers’ kicks and spins, Tazewell said.

Tazewell needed less clever costume engineering for the Sharks dance number “America,” which highlights the designer’s trademark use of color. Now set in the street instead of a compact rooftop, the scene is a kinetic swirl of vibrant colors, ruffles and petticoats that practically explode with the athletic choreography.

“Anita is the center of attention for that number,” said Tazewell, who dressed actor Ariana DeBose in an off-shoulder dress that’s as vividly yellow as her petticoats are red.

“It’s reflective of the joy and hope of the Latinx community at that time,” Tazewell said, adding that he hopes Anita’s dress becomes as iconic as the virginal white dress Natalie Wood wore as Maria in 1961.

In a nostalgic homage, that white dress returns. Anita now gives Maria the symbolic red belt, almost as a rite of passage. Maria’s subsequent costumes are more tailored, “so you get this sense that here is a young woman who is bursting to realize herself as a mature woman.”

There’s a lot of that kind of tension in this “West Side Story,” where the everyday toil of immigrant striving is both a burden and a catalyst to find a foothold. Spielberg, Tazewell and production designer Adam Stockhausen manifest those feelings in a reworking of “I Feel Pretty.” The original setting in a modest shop has changed to upscale Gimbels, where Maria imagines herself wearing the department store’s evening gowns instead of working in its cleaning crew. The update allowed the filmmakers to show how “we were working to have the Latinx community feel aspirational and make choices that help self-respect,” Tazewell said. “It reflected their yearning and what they wanted to become.”

Even in her simple apron, when Maria sings that she feels pretty, oh so pretty, we believe her. That’s the power of dressing well.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.