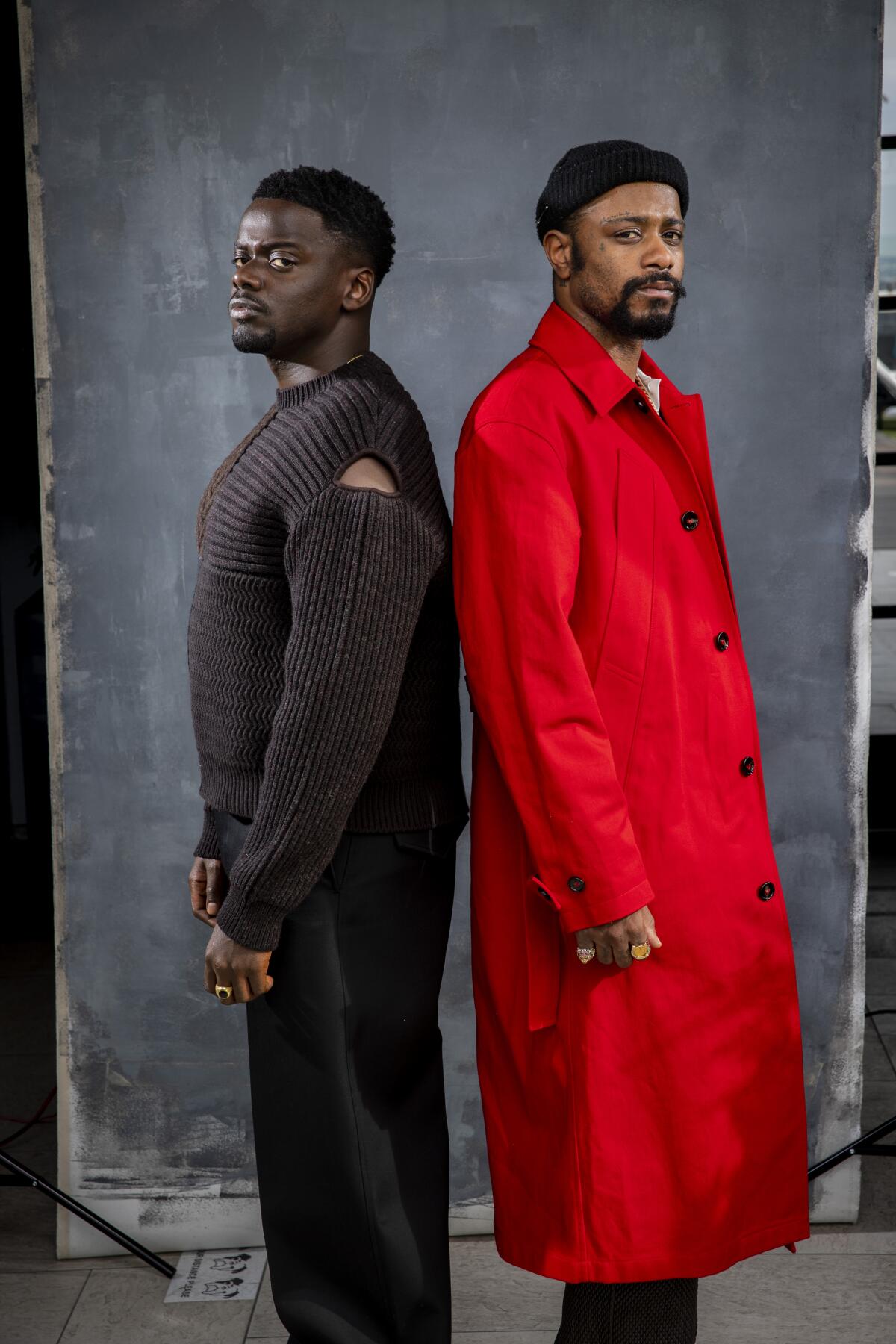

Daniel Kaluuya, LaKeith Stanfield share the love of a hero and freedom of performance

The same year Daniel Kaluuya and LaKeith Stanfield shared that unforgettable scene in Jordan Peele’s political horror classic “Get Out,” the moment where Stanfield screams the film’s title over and over again, the two men found themselves sharing the bill at a one-night performance of “The Children’s Monologues” at Carnegie Hall.

After the show, Kaluuya told Stanfield that he had agreed to join him on the film “Judas and the Black Messiah,” a tense portrait of Illinois Black Panther Party leader and defiant activist Fred Hampton and William O’Neal, the FBI informant instrumental in Hampton’s killing.

“Then the drinks started flowing, and I can’t remember the rest,” Kaluuya says. “LaKeith. Would you mind telling me?”

“I was like, ‘F—, that’s dope as s—,’” Stanfield says, laughing. We’re connecting via Zoom, Kaluuya electing to keep his video off, Stanfield initially doing the same (“we’re going to let our spirits speak”) before relenting. When Stanfield finally turns his camera on, it appears as if he’s floating in space, the sun rising above the Earth in his virtual background.

“He’s playful,” Shaka King, who directed, cowrote and coproduced “Judas and the Black Messiah,” says of Stanfield, a longtime friend for whom he wrote the part of O’Neal. “Unpredictable” is actually the first word that comes to King’s mind when thinking about Stanfield. “He’s very charming. He’s very sincere. Mischievous, certainly. There’s a vastness to him.”

Talking about Kaluuya, King describes the Oscar-nominated actor as “thoughtful in the actual sense of the word.”

“He’s thinking about things, really thinking through things,” King says. “I was fortunate to be working on this film with two of the most thoughtful people I’ve ever met.”

That abiding contemplation ran through our conversation, with each man listening intently to the other as they openly shared their experiences in life and acting. I spent most of the time listening, too, as they didn’t need much prodding when discussing matters so close to their hearts.

Black Panther Party chairman Fred Hampton’s widow Akua Njeri and son Fred Hampton Jr. were instrumental in bringing the story of “Judas and the Black Messiah” to the screen.

We learn many remarkable things about Fred Hampton in this film, one of them being that he had so much intelligence and intention at the age of 21. What were you like at that age?

Stanfield: S—, man, 21, I think I just got fired from my job for warrants I had for obstructing justice. [Laughs] I was outrunning the police, and there was this big chase, and everyone was running. I was trying to zigzag, thinking I could outrun the spotlight from the helicopter. For some reason, I thought I could outrun it, but I found out the radius was a lot larger than it appeared in my imagination.

So I got let go from my salesman type thing for AT&T. I was living in Sacramento at the time, and I had signed up on this film board, because I wanted to get in touch with anything that was filming if I could, try to get on the set. I checked my profile, and it had a bunch of unread messages. I hadn’t checked it in weeks. It was cold as hell, wasn’t nobody doing nothing. Then I finally checked it and Destin [Daniel Cretton], this guy I did a movie with five years ago when I was 17 or something, was doing a feature version of the short film, and he wanted me to come in and audition.

I got on the train from Sacramento, and I showed up at his front door and auditioned for “Short Term 12,” and that was the first role I did. I showed up literally on the last day they were casting. I remember it was in the evening. The day was going away. “Damn, I hope he’s still here.” I’m knocking on the door, and he opened, “Yo!” “Yo!” That s—’s crazy. That’s God.

Kaluuya: Twenty-one was a big year for me in terms of meeting myself. I was doing a play, “Sucker Punch,” at the Royal Court, where I played this boxer. I lost 42 pounds in three months — he was a lightweight — and it was the first lead role I ever had, and I got into a zone. I didn’t realize you could make work mean something. I didn’t realize it could speak to you. I knew, “Wow. This is what I’m here for,” because it was the sweet spot: When you’re in it, you want to watch it. And when you watch it, you want to be in it. And that’s been my North Star for everything. I just want to be in stuff I want to watch. At 21, that gave me an understanding of who I am.

Stanfield: That’s nothing but the facts right there. I had a similar experience with “Short Term 12.” I was not unlike the character I played, very untrusting of everybody. I kept to myself. Didn’t want to talk. Didn’t even want to eat with anybody. I was kind of damaged. I didn’t trust people in general, and I damn sure didn’t trust the white people in Hollywood. [Laughs] That’s how I was set up. It wasn’t until we finished that I got to feel like, “Wow, this s— is cool.” It was a relief. And it still feels that way. There’s not too many places you can feel completely free, but in the moments, in the performance, yeah. It’s releasing.

Kaluuya: It is. At the end of that play, I was liberated. I stepped out of that validation mind-set. I had a breakdown on stage on the last scene. I had let go of giving a f—. I got to the point where I knew that if I give all of myself, that’s enough. I met that version of myself. I did not hold that version of myself, because I still performed old habits, old thoughts, old beliefs. But I realized that all the errors of my life had been holding back, not trying to get hurt. I was watching this video the other day, Nipsey [Hussle]. “We’re here on earth to give ‘til we’re empty.” And I met that philosophy then.

Daniel, you told me once about the history textbook you found with information you weren’t learning about filled in the margins. How did you find out about Fred Hampton and the Black Panther Party?

Kaluuya: Self-education is the real education in life. I believe in conversations, not classes. The stuff I was incubated in [at school] wasn’t serving me. It was telling me I wasn’t enough. It was suggesting that I was “less than.” It wasn’t even suggesting that. It was telling me that white people are “more than.” And you’re internalizing that. But I don’t believe in that in the slightest. I believe in me, bro. So if I really do believe that in myself, that I’m equal to any man or woman on this earth, then I’m going to go toward content and scriptures that speak to the finest version of myself within myself. And that’s what the Black Panther Party’s philosophy and ideas instilled within me.

Stanfield: I hated school. And the worst class for me was history, because I always thought they were lying. They were talking about a bunch of white guys in wigs and how they laid the law and the land down and created everything. I never felt connected to it. I always had a rebellious spirit anyway and thought that everything was a damn lie and that my teachers were stupider than me. [Laughs] I could have paid some more attention in some of my other classes.

But I got to the age where I could do my own research, and, like Daniel said, I was attracted to certain things, and I stumbled across Fred Hampton. And I went on this whole shift. I used to be a troublemaker, running away from police, fighting, trying to get it however I thought that’s how you get it. That’s all I knew. But then I had this little shift in consciousness where I was like, “Damn.”

My brother wanted to be an astronaut, and he’d be studying all these interesting things, black holes and subatomic particles and dark matter. So I started diving into that, and it just brought me into a spiritual space, thinking about the macro and the micro and, man, just questioning everything. But I was always like that. We were raised very religiously. We were praying, and we had to close our eyes. But I would always open one eye and peek around and be like, “Wait a minute. Is this what’s really going on?” I’ve just been trying to find my own truth.

LaKeith, you’ve talked about how hard it was to play O’Neal, the man who betrayed Hampton, because you had such admiration for Hampton. Yet you really give him a full humanity.

Stanfield: For a long time, I didn’t even know if I wanted to see the movie. Maybe just let that thing live, you know. Oftentimes, I didn’t know if I was doing the right thing with this character, playing him with more dimensions than just being the villain. Maybe you should just be the villain. Maybe he doesn’t deserve dimensions. But it couldn’t just be a boogeyman. When I finally saw it, I was very happy, because I thought it showed Fred in a beautiful light and also might help people understand how they themselves might be aligned with a character like Bill O’Neal in more ways than they might know.

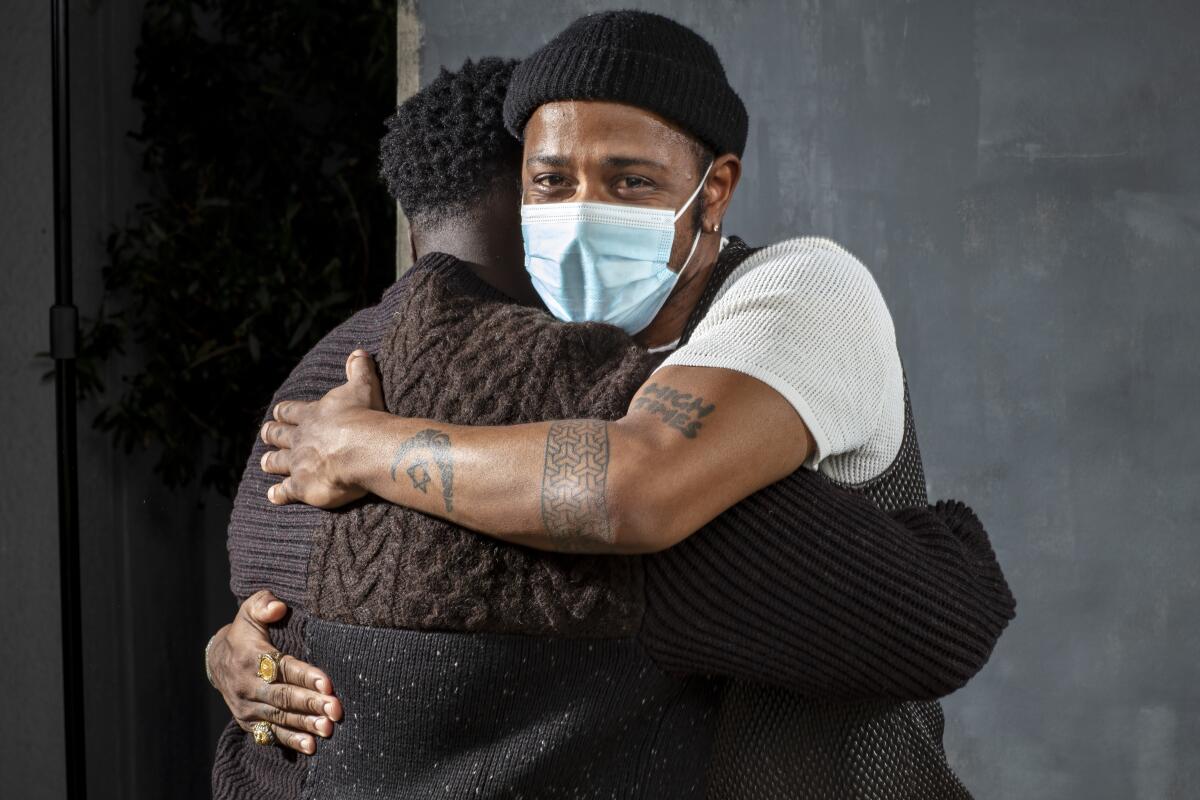

Kaluuya: I’ve got a story about LaKeith. I really haven’t told people about this. There was a scene of LaKeith driving, and the sound guy’s like, “Yo, there’s some sound on the mic. What the f— is that sound?” He’s looking everywhere, thinking he f—ed up. Then he realizes it’s LaKeith’s heart. Because in the scene, he had to get away. His heart is really beating. But that’s the level of commitment he’s showing in this. His heart’s literally in it. The sound guy had to turn s— down. That’s rare. He was all in.

Stanfield: To be honest, man, every damn scene I was lit. I had to be in all these stressful situations. Even my damn hair started falling out. It was hard. Just everything felt intense. Every moment.

Kaluuya: The day where I felt the weight the most was the [O’Neal betrayal scene]. I walked out of the trailer, and it felt like I was on another planet. I told Shaka that day, “I just want to say something. I want to do a speech.” I was just confronted by how much Chairman Fred meant to me, and a wave of emotion came up within me. I felt really ... I was in shock. I just didn’t have any control over it. How much he loved. And we’re doing this scene on the 50th anniversary of his death. Some things are just aligned.

Stanfield: “You can kill a revolutionary, but you can’t kill the revolution.” Those were his words, and they were a manifestation of what was happening. Here we were 50 years later, replicating it. He did it. And there’s going to be a whole new generation that meet his words, meet his mind, meet his love, the love that he had for these people and the love that he had for himself.

Yeah, after this experience, it just reinforced that this is the only kind of thing I want to be doing. I just got offered a commercial. It’s not my thing, so it wouldn’t even work. [Laughs] That s— would be terrible, because I don’t give a f— about it. You just gotta follow your heart. Otherwise, what’s the point?

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.