Ana Yency Lemús says her grandmother was pulled out of school in El Salvador at the age of 8 after experiencing physical violence and insults over her dark complexion and curly hair.

“Today we call that bullying, but it’s actually racism,” Lemús said.

In 2011, a group of Afro Salvadorans began a committee that would later become Afrodescendientes Organizados Salvadoreños (AFROOS). The organization’s objective is to empower Afro Salvadorans, educate Salvadorans about their contributions, and gain recognition for the various ways they contribute to the country’s heritage. Lemús is now the director of the organization.

A new wave of Afro-Latina entrepreneurs are embracing their natural hair and creating products that cater to curly and textured hair.

Many Salvadorans — regardless of their ethnic makeup — are raised to believe there are no Black Salvadorans. Many Salvadorans continue to revere mestizaje, a mix of Salvadoran and European descent, but Afro Salvadorans still face stigmas, and even erasure.

“People don’t want to listen when [I] want to discuss Afro Salvadorans or Indigenous peoples,” said Carlos Lara, an artist and anthropology student living in San Salvador. “It’s because [in El Salvador] we want to get closer to whiteness. That’s not new. It comes from the sistema de castas (caste system) that dates back to the colonial period, where people who were lighter-skinned were treated better.”

Lara’s artwork is a colorful portrait of Afro Salvadoran culture that he proudly displays in his atelier.

Latinidad is an ever-expanding concept, but it has not often made space for the Garifuna people who come from various regions of Central America.

Although he has Afro Salvadoran ancestry, Lara’s family often told him there were no people like him in his home country, with one of his family members going as far as avoiding local merchants who were Black.

“I remember hearing that ‘there are no Black people in El Salvador’ at school and home,” Lara said.

Lara explains that he began to question the validity of the assumption that “there are no Black people in El Salvador” when he noticed negative comments about a local tortilla vendor.

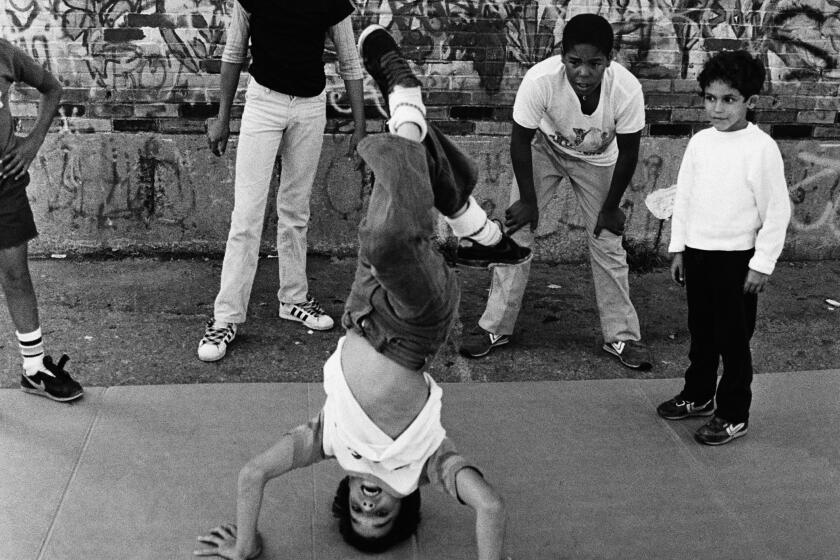

Break dancing was created in the Bronx by Black and Puerto Rican youth during the 1980s and has since expanded to the world.

“I remember my grandma saying that she didn’t want to buy tortillas from Concha because she’s Black,” he said. “Then I became confused about why we were told there are no Black people in the country.”

In his activism, Lara attests that the attitudes of some Salvadoran people can pose challenges to creating positive change.

“Many people here keep saying we’re all the same. They don’t want to accept that El Salvador has African heritage.”

This comic is for the diaspora Salvis and navigating our complicated relationship with our familial homelands.

Cultural contributions to El Salvador that can be traced to Africa include rice, horchata, plantains and añil (the decorative use of indigo).

Lemús says La Cochinita is a dish from her hometown of Atiquizaya that can also be traced to Afro Salvadorans. It’s typically made of pig head and other parts of the animal that are often discarded, and is similar to barbecue in the U.S.

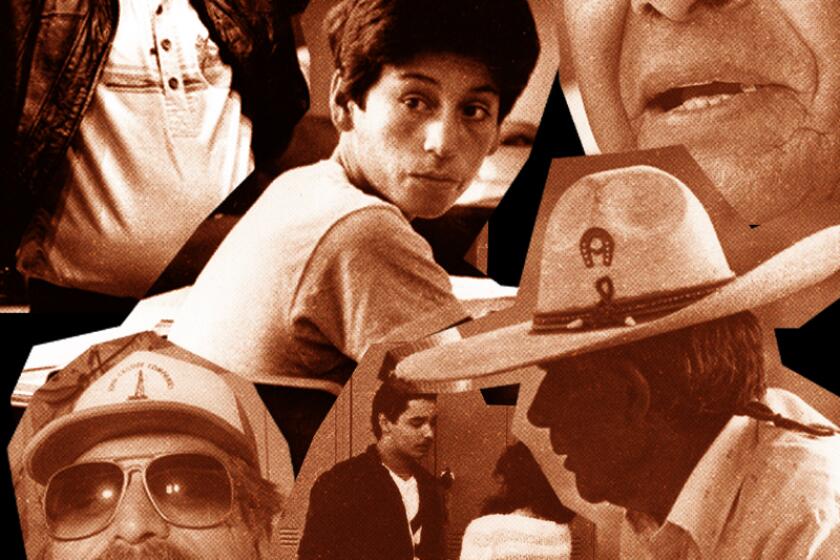

Historically, there is a basis for why some Salvadorans believe there are no Black people in the country. Gen. Maximiliano Hernández Martinez was the president of El Salvador from 1935 to 1944. He was a dictator who created an immigration law that forbade most ethnic groups from migrating to El Salvador, but favored people of European descent. This, he believed, would promote racial mixing (blanqueamiento) between local Salvadorans and new European immigrants that would “whiten” Salvadorans.

The R&B themed yoga classes might suggest added choreographed routines to newcomers, and while it includes an occasional twerk and body roll, yoga and its meditative elements take precedence.

According to Lara, there’s a major misunderstanding of these events in modern-day El Salvador. Many mestizo Salvadorans believe Hernández Martinez kicked Salvadorans of Black descent out of the country.

“He prevented the entry of African immigrants,” Lara said. “That’s not the same as kicking Afro Salvadorans out.”

Zaira Funes is a preschool teacher who grew up in San Pedro.

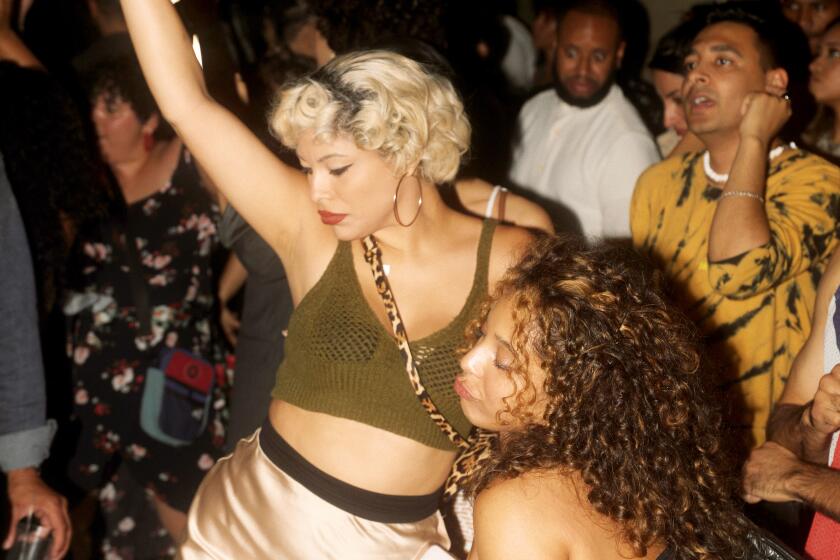

It’s clear there’s a desire for Caribbean culture in L.A., as more and more Caribbean Latines make their way to the West Coast.

“Growing up, I didn’t get a sense of Central American representation,” Funes said. “Salvadoran representation was always focused on war, poverty or gangs.”

It was an art exhibit in the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach that gave Funes the idea to start her social media accounts, Centam_Beauty on the site formerly known as Twitter and Instagram. She also runs Isthmus Roots.

“I saw [some] art from Latin American countries but I only saw two pertaining to Central American artists,” Funes said.

More than four decades ago, groups of Black and Latino journalists embarked on an endeavor to tell stories about their communities that the Los Angeles Times was failing to showcase.

Funes’ work and education efforts have been hailed for celebrating the beauty of El Salvador, the rest of the isthmus, and the contributions of Afro Salvadorans.

She recounted receiving comments about her ethnic makeup from friends in the eighth grade who saw pictures of her family.

“My friend saw a picture of my aunt and asked if I was mixed because my aunt has more melanin and curly hair,” Funes said. “It kind of took me by surprise because I had never been asked this question before.”

Along with talking about her own heritage, Funes has also shared the work of other Afro Salvadorans in El Salvador and the diaspora.

In Los Angeles, Afro Salvadorans can find allyship within other Afro-Latinx communities, Funes explains. Black culture in the U.S. and that of other Black and African immigrants are also important sources of camaraderie that can help Afro Salvadorans feel less alone, and provide outlets that Salvadorans in the country don’t have, she says.

Lemús is optimistic about her work educating Salvadorans, and though it’s hard to change people’s views after centuries of being told that “there are no Black people in El Salvador,” she’s seen progress.

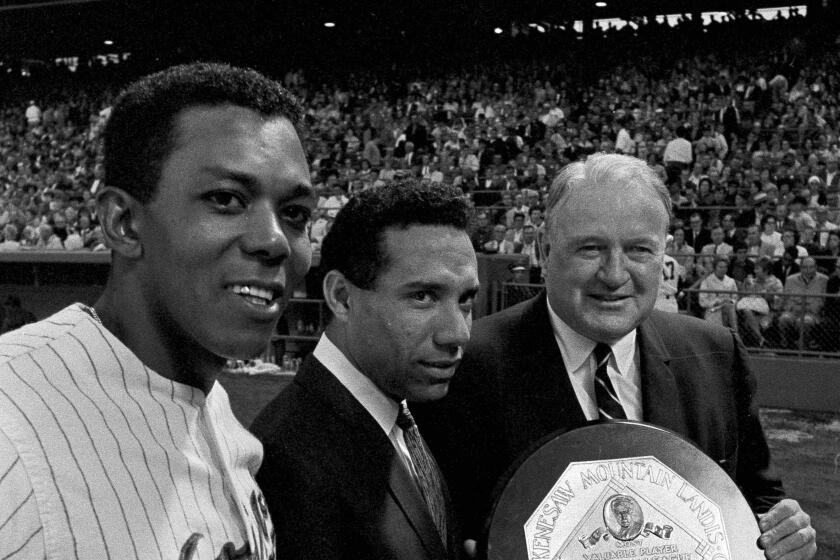

Zoilo Versalles and Tony Oliva were teammates on the Minnesota Twins. Both players were involved in a historic MVP race that would crown the first Latino MVP in the MLB.

“We went to a United Nations forum and talked about the existence of Afro Salvadorans,” Lemús said. “AFROOS has created a school called Miguel Angel Ibarra, named after the first man who publicly announced his Afro Salvadoran identity.”

August is now El Salvador’s Black History Month, and Aug. 29 is an especially important day of recognition for Afro Salvadorans in the country and the diaspora. That date is el Día de la afrosdescendencia salvadoreña (loosely translated, Aug. 29 is Afrodescendants Day in El Salvador). It was first celebrated in 2014.

“We need the world to know that Afro Salvadorans exist,” Lemús said. “We need to breathe life into this forgotten history.”

Ingrid Cruz is a freelance writer and journalist covering pop culture, mental health and social justice issues. She grew up in L.A. and has lived in Mexico City, Washington, D.C., Mississippi and Buenos Aires. You can follow her on social media @ingridquerubina.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.