Palm Springs promises to ‘right that wrong’ for Black, Latino community destroyed in 1960s

Acknowledging its role in the destruction of a local Black and Latino neighborhood, the Palm Springs City Council promised Thursday to “right that wrong.”

Council members did not specify what they plan to do for the survivors of the community leveled in the 1960s, however, and made no mention of paying reparations to the families whose homes were demolished.

Residents of the Section 14 neighborhood on the outskirts of Palm Springs were working-class tenants who lived on tribal land because they couldn’t obtain housing in the highly segregated desert community.

At the time, Section 14 residents were responsible for turning Palm Springs into a desert oasis, working as maids, builders, chauffeurs and at other jobs, according to an administrative claim for reparations filed by the former residents and their descendants. In 2021, the city apologized for its actions surrounding the displacement of the neighborhood, but officials have provided little insight into what could happen next.

On Thursday, Palm Springs gave a glimpse into its prospects for the displaced community. Officials promised to continue conversations on Section 14 with the former residents and descendants, but did not mention any form of direct compensation.

Former residents and their descendants say the city of Palm Springs owes them up to $2 billion in damages for the forcible removal in the 1950s and ‘60s of cooks, chauffeurs and builders who helped turn the desert town into a playground for the stars.

The City Council agreed to build more affordable housing, Mayor Jeffrey Bernstein announced after a closed-door session discussing the administrative claim, which could act as a precursor to a lawsuit by the Section 14 group. The city promised to “explore ways that we can increase economic opportunities; especially with small businesses in underserved communities,” Bernstein said in a statement.

“My colleagues and I recognize that city funds were used to clear land which housed individuals and families who were tenants on the property, including minority groups,” Bernstein said after Thursday’s City Council meeting. “We know that we as a city need to right that wrong, and in today’s closed session we collectively agreed on a number of steps to accomplish that goal.”

City officials promised to study the cost for a healing or cultural center dedicated to Section 14 and the hiring of a historical consultant to study the issue.

Attorney Areva Martin, who represents the former residents and descendants of Section 14, said in a statement that the group was “encouraged that the City of Palm Springs has heard our call for justice and has committed to taking tangible steps to make the Section 14 Survivors whole.”

“We look forward to working closely with the City Council to reach a reasonable and just resolution, so that we can turn a page on this chapter of Palm Springs’ history and move forward,” Martin added.

But the two sides cannot agree on how many homes Palm Springs destroyed or the cost to build those homes.

The city argues that Palm Springs is liable for the destruction of only 145 homes, while the group behind the claim argues it was 350 homes, according to a counterproposal from the city to the Section 14 Survivors shared with The Times on Friday.

The two sides also disagree on the value of the homes and personal property destroyed. The city put the number at just $3,000 per site in 1965, or roughly $29,500 per site today when adjusted for inflation, according to Palm Springs City Atty. Jeff Ballinger. That would amount to $4.2 million in total.

The Section 14 group said the homes were worth $18,000 and the personal property $4,200 in 1965, putting the total value for monetary damages today at $15.7 million.

Ballinger called the city’s proposal “a historic move.” If there were any additional state or federal sources to supplement those payouts, he said, the city said it would be willing to include those as well — but the Section 14 group would need to help find those sources.

Martin called the proposal “a first step, but the survivors and descendants are continuing to meet with the city and negotiations continue.”

The plot of land that made up Section 14 belonged to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, but was held in trust by the federal government.

It was home to a predominantly Black community in addition to migrant workers from Mexico and South America in the 1950s, according to historical records.

Palm Springs curbed short-term rentals in some neighborhoods. Now homeowners are watching their property values drop, sometimes drastically.

A federal arrangement barred tribal members from leasing parcels for more than a few years. But in 1959, federal law eased development restrictions, clearing the way for the Indian landowners to offer prospective tenants 99-year leases. This offered the city and tribal land owners a huge financial opportunity to cash in on the land.

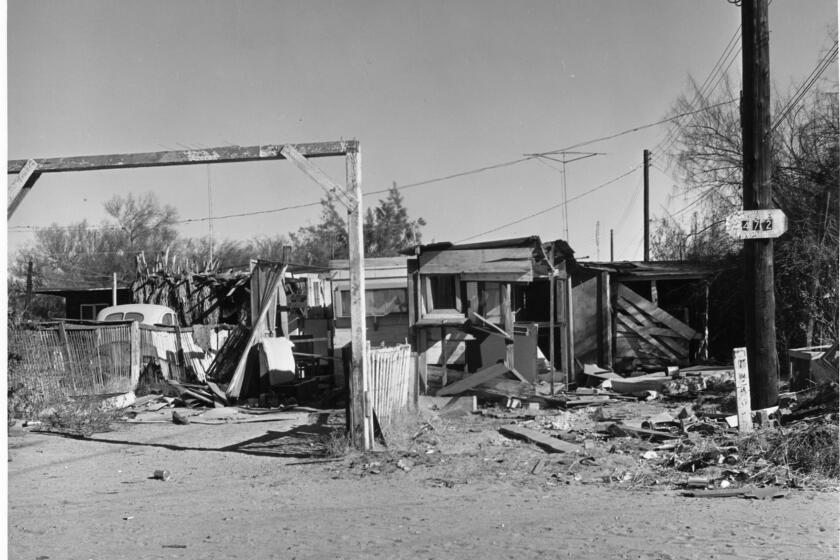

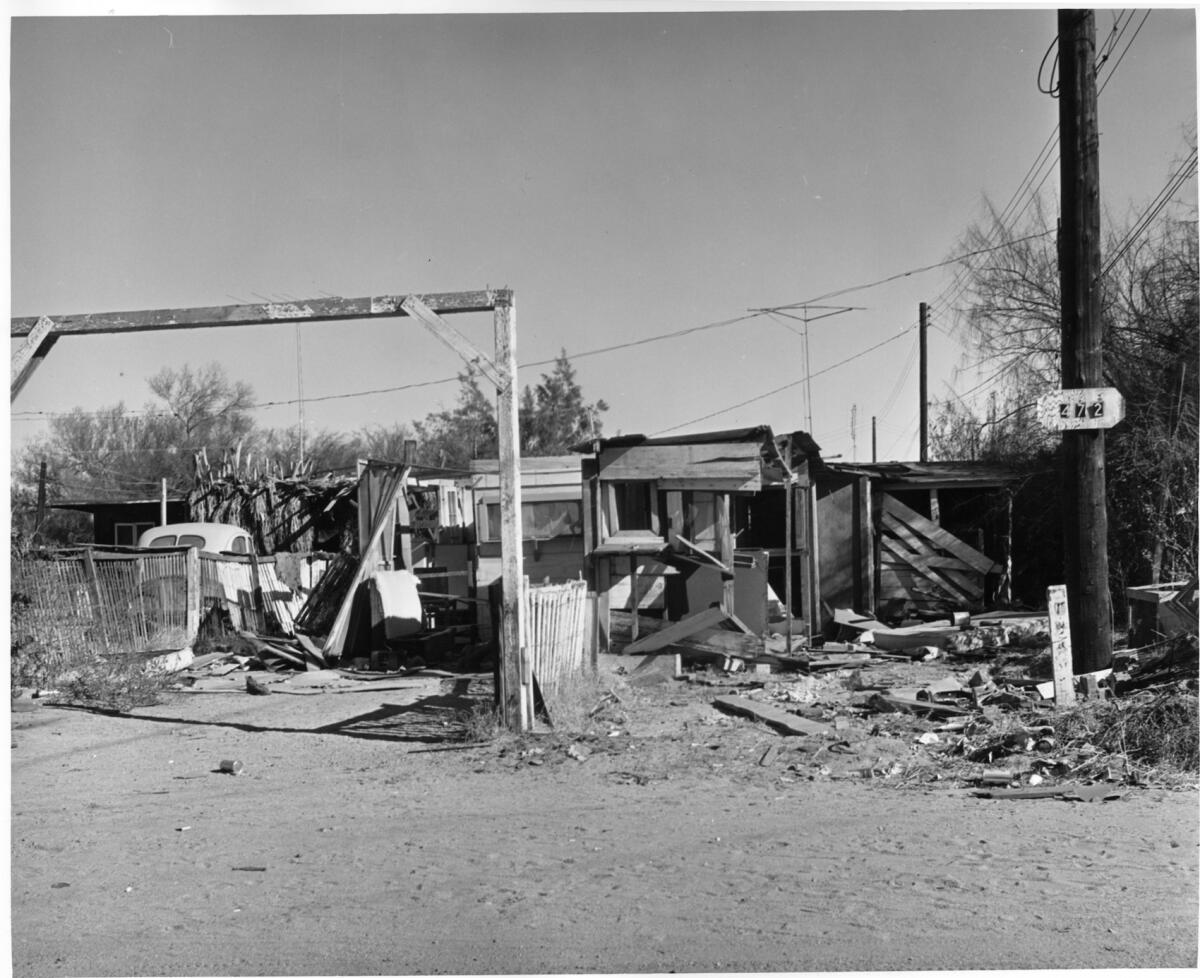

All the structures in Section 14 were condemned by the city and the tribal landowners. By 1966, the city reported to the Bureau of Indian Affairs that it had been able to “demolish, burn and clean up approximately 200 dwellings and structures.”

A state probe in 1968 determined that the city acted without giving residents in Section 14 the required notice that they were being evicted before the homes and the personal belongings in them were destroyed. State officials at the time referred to Palm Springs’ actions as a “city-engineered holocaust.”

The families who built their wooden shacks and concrete houses in Section 14 were removed to make way for luxury properties, including a Hilton hotel, and residents such as Pearl Devers watched her neighborhood go up in flames while local firefighters stood nearby.

“This was done by the city, the city of Palm Springs Fire Department, regardless to what some are saying that the city had no involvement,” Devers recently told The Times. “I don’t know how they can claim that when the city Fire Department were the culprits.”

The Ebony Beach Club never saw the light of day, but the city of Santa Monica wants to make things right.

Devers, president of the Section 14 Survivors group, told The Times that the neighborhood’s destruction devastated her family. Her father, who built their home, told Devers’ mother and her siblings to leave while he tried to save the community, staying behind while Devers and her mother moved to nearby Indio. After their home was gone, her father turned to alcoholism and never recovered, she said.

“We want to restore our history and we want to give the Palm Springs City Council a chance to really set a precedent to show the nation and the world how to heal, how to resolve an issue that is so painful,” Devers said before Thursday’s announcement.

The area of eastern Palm Springs is now the site of a casino, convention center and hotels. Concrete slabs found on undeveloped parcels of land are all that are left of Section 14, according to the former residents.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.