A colleague’s suicide exposes a crisis among L.A.’s restaurant inspectors

It was the worst kind of conference lunch.

In late August, more than 30 people departed a three-day-event at the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles sick with Shigella, a bacterium that can spread through infected food. At least four guests ended up in the hospital, including one woman who said she was told by a doctor that her kidneys were shutting down.

To prevent outbreaks from contaminated food, the L.A. County Department of Public Health aims to inspect “high-risk” food facilities — typically those with full-service kitchens handling raw meat — three times a year, according to department procedures reviewed by The Times.

But that rarely happens.

Of the roughly 18,000 “high-risk” food facilities that should have been inspected three times last year, fewer than 2% were, internal county records reviewed by The Times show. Roughly three in 10 — 5,365 —weren’t inspected at all. A well-reviewed Hollywood taqueria hasn’t been visited since spring of 2021.

“It seems like a ridiculously high number,” said national food safety expert Darin Detwiler, who teaches food policy at Northeastern University. “That should never be like that for your high-risk facility.”

At least 32 people attending a union conference at the Westin Bonaventure in downtown Los Angeles last month were sickened from an outbreak of Shigella bacteria.

More than a dozen current and five former L.A. County health inspectors interviewed by The Times say the paltry inspection numbers are the result of an agency in crisis.

Since the pandemic, inspectors say, they have been pushed to the breaking point, given a Sisyphean task of trying to keep thousands of restaurants safe while their ranks shrink. High vacancy rates and mismanagement have put an untenable strain on the remaining employees, they say, leading to rushed, subpar inspections.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

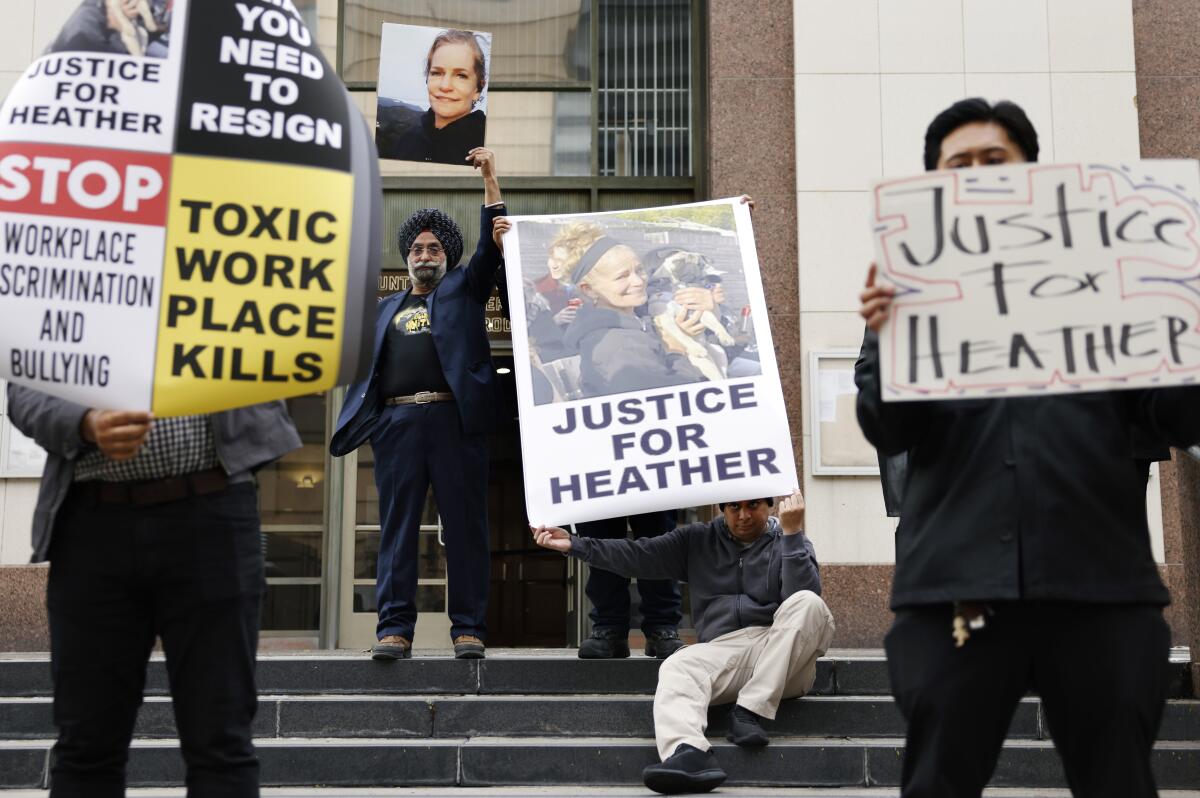

Morale plunged to a new low last month after the workplace suicide of a 55-year-old health inspector, leaving an already demoralized workforce reeling. In the chaotic month since, employees have called for an outside investigation and demanded their bosses’ resignations.

Teamsters Local 911, the union representing the department’s inspectors, says the long-simmering internal dysfunction threatens both employees and the eating public — who expect to enjoy their food, not be sickened by it.

“This is the importance of having a functioning government: If you don’t do the jobs, people die,” said union representative Judith Serlin. “Right now, the people who are doing the work are saying ‘Enough’ ... and no one’s listening to us.”

The main kitchen at the Westin Bonaventure, considered a high-risk food facility, was going on eight months without an inspection when the outbreak occurred, inspection records show. Before that, it had been three years.

Marriott International, which oversees the hotel, did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s impossible to say if more inspections could have prevented the outbreak, which county investigators believe was likely the result of an employee, asymptomatic for shigella, preparing the chicken curry and tuna salad wrap served to conference-goers for lunch.

But in general, health experts say, inspections serve a critical role in preventing outbreaks, catching problems — such as potentially, asymptomatic employees not washing their hands — long before they snowball into the type of mistake that can sicken a customer.

On Sept. 1, a week after the conference, health inspectors returned to the hotel kitchen and found eight live German cockroaches, one dead American cockroach and roughly 20 fruit flies.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

The following workday, Liza Frias, director of the department’s environmental health division, sent a note to her staff.

“Over the past six months, the number of confirmed outbreaks at food facilities and the numbers of cases involved in a single outbreak has sharply increased,” she wrote. “We are all responsible for preventing food borne illness.”

But inspectors say these prevention efforts are faltering. In 2019, inspectors visited nearly 12,000 of the riskier food facilities three times, the county said. Last year, only 327 establishments received three inspections, internal records show.

Michael Matibag, a six-year employee of the department, said he’s struggled to get to high-risk restaurants even once a year. When he made it to the kitchen of a Korean gastropub in La Verne in October, he said, rats had thrived in his year-long absence.

“I’m talking like 50 pieces of individual rat feces,” said Matibag, who said that he wanted to see his division better run. “Fifty pieces of rodent dropping isn’t going to happen overnight.”

A senior inspector said they now try to fully inspect certain large restaurants in about 25 minutes. It used to take them an hour and a half.

“We started rushing through these inspections,” said the inspector, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss his job. “We’ve been doing half-assed inspections.”

The department said it expects all staff to conduct “full, high-quality” reviews of food facilities, and blamed the lack of inspections largely on the COVID-19 pandemic, which overburdened health departments nationwide with employees now asked to enforce new safety protocols. Many resigned.

A spokesperson said the agency is budgeted for 244 field inspectors but is down 69 — vacancies it is struggling to fill due to an “industry-wide lack of qualified applicants.” The spokesperson said 27 new inspectors are in training.

“These vacancies have impacted [the Department of] Public Health’s goal to meet industry best practices, including inspecting high-risk facilities three times a year,” the agency said in a statement. “Nevertheless, diners should feel confident that complaints that are received are immediately investigated.”

The department said the number of foodborne outbreaks in 2023 closely aligned with pre-pandemic levels.

Department officials did not dispute the inspections data but said they felt it was more accurate to look at figures by fiscal year, which aligns with the county’s budget cycle. Data for the most recent fiscal year provided by the county shows fewer high-risk facilities going uninspected — a little over 2,100 compared with 5,300 for the 2023 calendar year — but roughly the same percentage — less than 2% — receiving three inspections.

Some health experts warn that the data do not bode well for the West Coast’s culinary capital, which is likely to see demand only grow in the coming years, with the 2028 Olympics bringing a deluge of new food trucks and eateries to serve the influx of tourists.

It also raises questions about whether thousands of restaurant owners are getting what they paid for.

Because high-risk facilities are supposed to be inspected more often, they pay more in permit fees to the county agency to cover the cost. If most full-scale restaurants aren’t getting inspected multiple times a year, inspectors said, owners should question why they were asked to pay more in license fees.

The California Restaurant Assn., which represents restaurants across the state, said in a statement it looks forward to working with the county to “ensure restaurant permit fees are better aligned with the services provided.”

Employees say the sharp decline in inspections not only represents a potential health hazard to the public, but also hints at a workforce in deep distress.

On Feb. 13, their boss was in the hot seat.

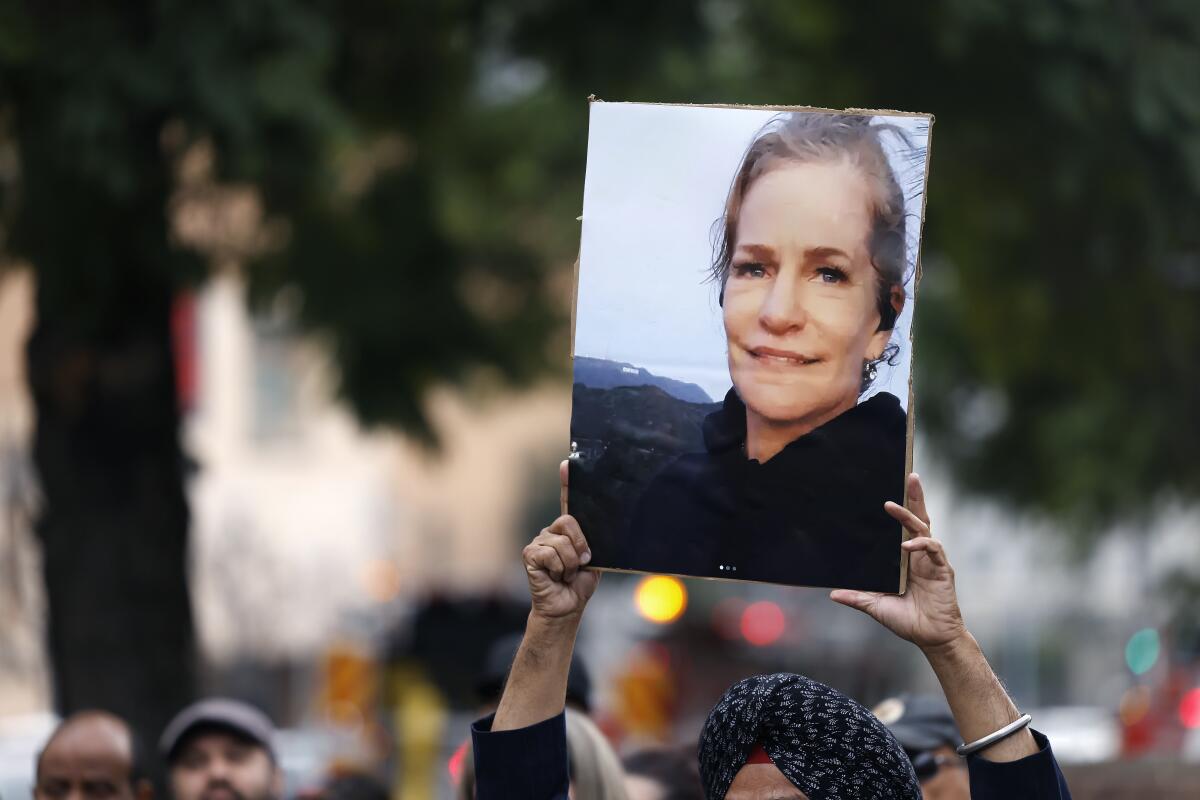

A swarm of furious employees confronted Barbara Ferrer, director of the public health department, after a longtime inspector, Heather Hughes, took her own life at her office building.

During a heated, hours-long meeting, Ferrer listened as employees raised longstanding concerns within the inspection branch, responsible for safeguarding the county’s restaurants, rental properties, pet stores and massage establishments, among other facilities.

Too many people were leaving for other jobs. Trust in management had eroded. One employee said she’d filed 34 grievances. Another said they felt like a damaged “zombie.”

“There are restaurants that haven’t been inspected in maybe more than a year,” one employee said, according to an audio of the meeting. “We’re extremely stressed out. We feel, to be honest with you, very abused and mistreated.”

Experts caution against attributing a person’s suicide to a single cause, and friends and family acknowledge work problems alone don’t paint a full picture. The department has repeatedly cautioned staff to not conflate workplace grievances with the tragic death of a colleague and emphasized there is “no evidence to date linking Ms. Hughes’ death to workplace conditions or Public Health management.”

But employees have continued to link the workplace suicide with conditions inside the environmental health division, where Hughes, an eight-year inspector known for her camouflage crocs and love of alternative ‘80s music, had grown increasingly despondent, according to interviews with colleagues, friends and family.

Hughes told her sister, Hollie Chairez, that she was struggling at the agency, trying to keep up with younger employees who were able to do four inspections to her one, Chairez said in an interview. Other colleagues have told her they believe Hughes was bullied by management for failing to keep up, she said. Last May, Hughes texted a former colleague that “things have hit another level that are indescribable here.”

“I don’t think the job pushed her [to end her life], but I think it nudged her closer,” said Chairez, who said many of her sister’s colleagues have reached out to her in the last month. “Everyone’s experience seems to be very similar to my sister.”

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Susanne Lewis said she met Hughes in 2012 at Wild Card Boxing Club, a gym in Hollywood. Lewis said Hughes was delighted when she landed the job, which meant she could start using her chemistry degree and stop selling her blood plasma for gas money.

But in the last few years, she said, Hughes had become disenchanted with the dream job. As they jogged together, she said, Hughes would tell her stories about a colleague belittling her for the casual way she wrote her inspection reports. She said Hughes had attempted suicide twice in recent months.

The day before she ended her life, she visited Lewis at her home.

“She literally said to me on Wednesday this is at least 50% about work,” Lewis said. “She just kept saying all through January, ‘I can’t go back to work. I just can’t go back to work.’”

Hughes’ colleagues say her death, while likely caused by many factors, has made inspectors’ brewing frustration impossible to ignore. The department has since promised to hire an outside expert to “assess areas for improvement,” according to an email sent to staff, and floated a review of exit interviews to understand why people are leaving.

“We have heard from a number of environmental health employees regarding various workplace concerns,” the department said in a statement, which called Hughes a beloved, dedicated public servant. “We are striving to work collaboratively with staff and labor partners to address them.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 988. The first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Or text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.