Are L.A.’s anti-camping laws failing? We went to 25 sites to find the truth

In the final days before Tuesday’s municipal election, a leaked report purportedly exposing systemic failures of Los Angeles city’s anti-camping law reignited a heated debate among the law’s supporters and opponents on the City Council.

The report, prepared in November by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, said only a small fraction of homeless people who were relocated from encampments had obtained permanent housing — and that hundreds simply moved back, in some cases more than were initially there.

The report, which had not been released to the public, was leaked to news organizations late last week, prompting foes of the law, known as Municipal Code 41.18, to say they had been vindicated.

“We’ve known for years that shuffling people from block to block with 41.18 doesn’t work, and now there’s city data proving it,” Councilmember Hugo Soto-Martínez said. “We know that encampments swept with 41.18 nearly always return, and we spend millions of dollars every year on this ineffective criminalization of homelessness.”

To gauge the present conditions of the camp locations, The Times on Friday and Monday surveyed all 25 spots identified in the report as being “repopulated” by 20 or more people. At most of the locations, there were no tents or makeshift shelters, or only one or two, within the 500-foot radius buffer zones where camping is prohibited.

The conditions offered a much more complicated picture than the LAHSA report about what happened in the anti-camping zones created by the council.

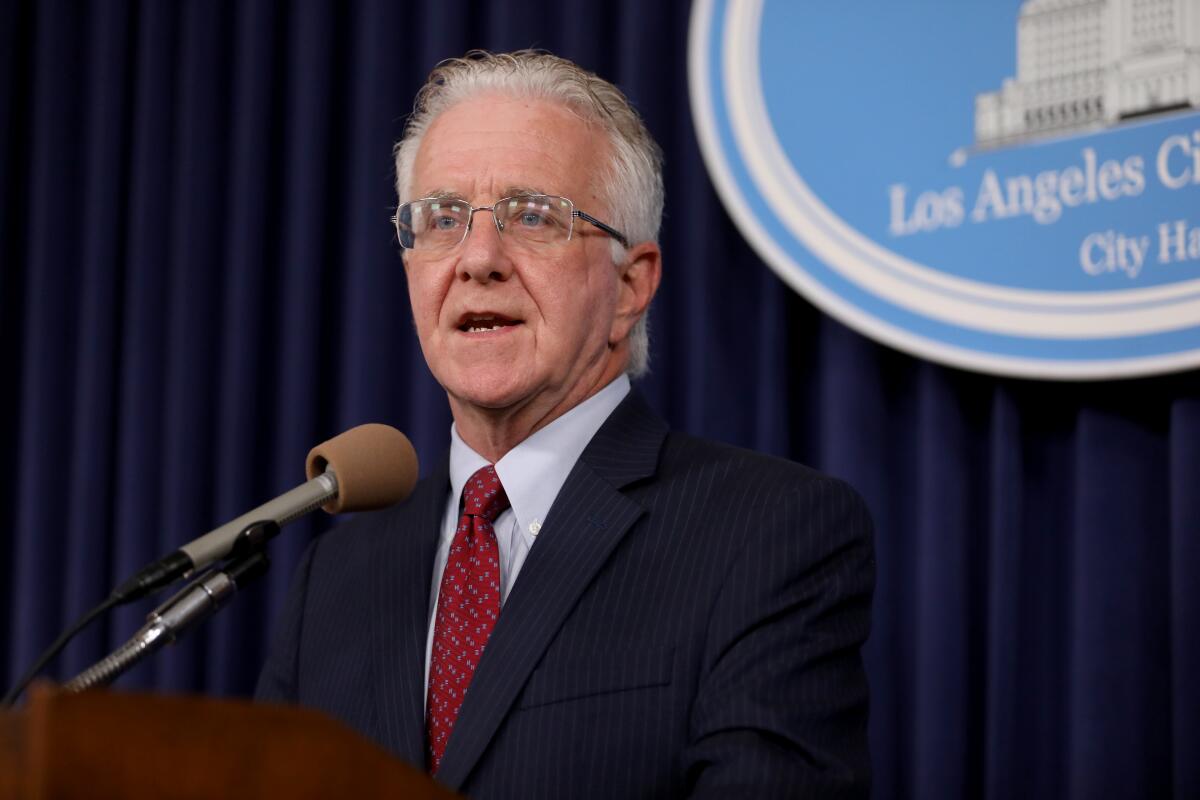

Council President Paul Krekorian, a supporter of 41.18, blasted the report as “clearly faulty and incomplete at best, and perhaps even deliberately misleading.”

Krekorian also sharply disputed a Friday report on the digital news site LAist that suggested the city was keeping the report “in the shadows” because of “widespread anxiety and fear about releasing the findings.”

Krekorian said the report’s flaws made it unsuitable for guiding policy. LAHSA, he said, is only one of several agencies providing information for an overall analysis of 41.18 requested by the council.

“Too often, half-baked information based on faulty data and assumptions has been the basis of bad policymaking and demagoguery, and the council must demand information that the public can count on,” he said.

On Tuesday, the advocacy group Los Angeles Community Action Network released its own report, Separate and Unequal, urging the council to revoke the law and return to “compassionate, community-driven and non-coercive outreach.”

Councilmember Katy Yaroslavsky, who pushed for the assessment of the anti-camping law last year, will withhold comment until the city’s chief legislative analyst completes her report, said Yaroslavsky’s communications director, Leo Daube.

“The LAHSA analysis is just one piece of the final CLA report,” Daube said. “We are looking forward to seeing the final CLA report when it comes out and hope it comes out quickly.”

Chief Legislative Analyst Sharon Tso, who is reviewing the LAHSA report, told The Times in an email that she was “seeking some clarifications” on the information provided by LAHSA and was “still working thru it.”

LAHSA issued a statement saying it stood by its report and had cooperated with the city in answering questions.

Assessing the effectiveness of the anti-camping law is complicated by the fact that council members had two separate goals for the law: restore access to public spaces and move encampment residents into housing.

The City Council voted in 2021 to amend its anti-camping law to allow the council to designate specific areas — senior centers, freeway overpasses, homeless shelters and other locations — as off-limits to tents.

To counterbalance the primary goal of clearing people from those sensitive areas, and to preempt constitutional challenges, the council also established a street engagement strategy requiring outreach to offer shelter or housing to everyone being ordered to leave.

The following year, the council expanded the law, barring encampments within 500 feet of any school or day-care center. That change sparked furious protests from homeless advocates, who repeatedly attempted to shut down council meetings where the law was being considered.

The report characterized the law as failing to meet the housing goal because only 16.9% of the nearly 1,900 people counted in the camps were placed into housing. That was almost exactly the rate for LAHSA’s outreach efforts in general. Only two people obtained permanent housing and more than half of those who went into a shelter later left and were presumed to have returned to the street.

In contrast, Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program, designed to induce people to leave encampments voluntarily, has moved more than 2,100 people indoors, with nearly 400 receiving permanent housing and more than 400 falling back into homelessness, according to LAHSA figures from last month.

When assessing the law’s primary goal of clearing encampments, LAHSA said its analysis was hampered by inadequate data, which it blamed on the city’s lack of universal tracking standards. LAHSA acknowledged that it could not determine when enforcement occurred at designated locations or if the encampments there had, in fact, ever been cleared.

Nonetheless, the report described the law as “relatively ineffective” because more than 80% of those encampments “repopulated” with people who were previously there or came from another encampment. The accompanying data file showed that nearly 40% of the 174 locations studied had repopulated with more than the number of people initially there.

That conclusion did not reflect the present condition at the sites. Rather, it was based on the total of all outreach contacts made in the zone in and around each designated site after no-camping signs were posted and the 14-day notice period ended.

The Times’ visits to 41.18 locations over the last week found that most were either entirely free of encampments or had substantially fewer than the period before anti-camping signs were installed.

Several of the sites have also been targeted by the mayor’s Inside Safe program, leaving unclear which program was responsible for success or failure at certain locations.

In some cases, people with firsthand knowledge said the computer-generated numbers did not match their experience on the ground.

Three locations still had entrenched encampments. One, an area downtown where five enforcement zones largely overlap (significantly multiplying the apparent number of repopulations), has had persistent encampments despite both enforcement under the anti-camping law and outreach under Inside Safe.

The Times found 51 tents and shelters there Monday, two-thirds in areas where Inside Safe operations have been conducted.

In Yaroslavsky’s Westside district, several tents occupied the Expo Line right-of-way and the nearby Pico and Exposition boulevard underpasses at the 405 Freeway. People staying there said police do not bother them as long as they remain orderly. It’s one of many sites designated as a no-camping area by Yaroslavsky’s predecessor, Paul Koretz.

Yaroslavsky has not designated any new sites and has not pursued enforcement at the location, Daube said. That could change this fall, he said, after the opening of the district’s first interim housing facility for the general homeless population.

Daube said Yaroslavsky’s concern is that enforcement of 41.18 “pushes people from block to block,” but that she would support the no-camping ordinance “when it makes sense and when there are beds to offer.”

At another persistent encampment, 29 tents remained along a dirt road near Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park in Harbor City, a significant drop from five years ago when some 100 homeless people were reported living in the area.

That location was also targeted by the mayor’s Inside Safe program last year.

Further confounding the picture, five of the no-camping locations were centered on shelters where people often congregate, either hoping to obtain a bed or after being evicted for violating rules.

Stephanie Klasky-Gamer, president and chief executive of LA Family Housing, said she doubted, but could not contest, the report’s finding that 60 people had populated the zone around the organization’s North Hollywood headquarters after it was designated for no camping, or that 84 people had since been in the area.

“One tent goes up, then five more,” she said. “Then it gets cleared.”

On Friday, there were no tents on the sidewalk behind the building, where they usually turn up. Seven tents were scattered along two blocks of the power line right-of-way one block to the west.

Klasky-Gamer, who does not support the anti-camping law, said it had no bearing on whether encampments occurred there or were cleared.

“We didn’t invite people to be outside our building, but if they were they were treated with respect,” she said. “We never had to use the threat of 41.18. We just used the resources that already existed.”

The most effective, she said, was outreach coupled with CARE Plus, the city Sanitation Bureau operation that allows people to return to an area after it’s cleaned.

A stretch of San Fernando Road in Krekorian’s Northeast Valley district illustrates the difficulty of measuring the effectiveness of the anti-camping law.

In April 2022, when The Times first surveyed 41.18 locations, it was occupied by an almost uninterrupted row of dilapidated RVs. LAHSA’s report said it was populated by 31 people when designated for enforcement and was subsequently repopulated by 21.

On Friday, only two RVs remained on the mile-long border of the Metrolink tracks. Much of the road’s dirt shoulder was blocked by concrete barriers and the rest was empty. But the transformation was not a result of 41.18 enforcement, Krekorian communications director Hugh Esten said.

That stretch of San Fernando Road had long been posted for no overnight parking, a rule that was not being enforced. When the date for a scheduled resurfacing of the road arrived, people were told they had to leave. Some RVs left, and those that remained were towed.

Esten contested the report’s finding that only one of the 31 people had been housed. The council office and LAHSA had engaged 23 people and found shelter for 14, he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.