California tightens rules on worker exposure to poisonous lead. ‘The evidence is undeniable.’

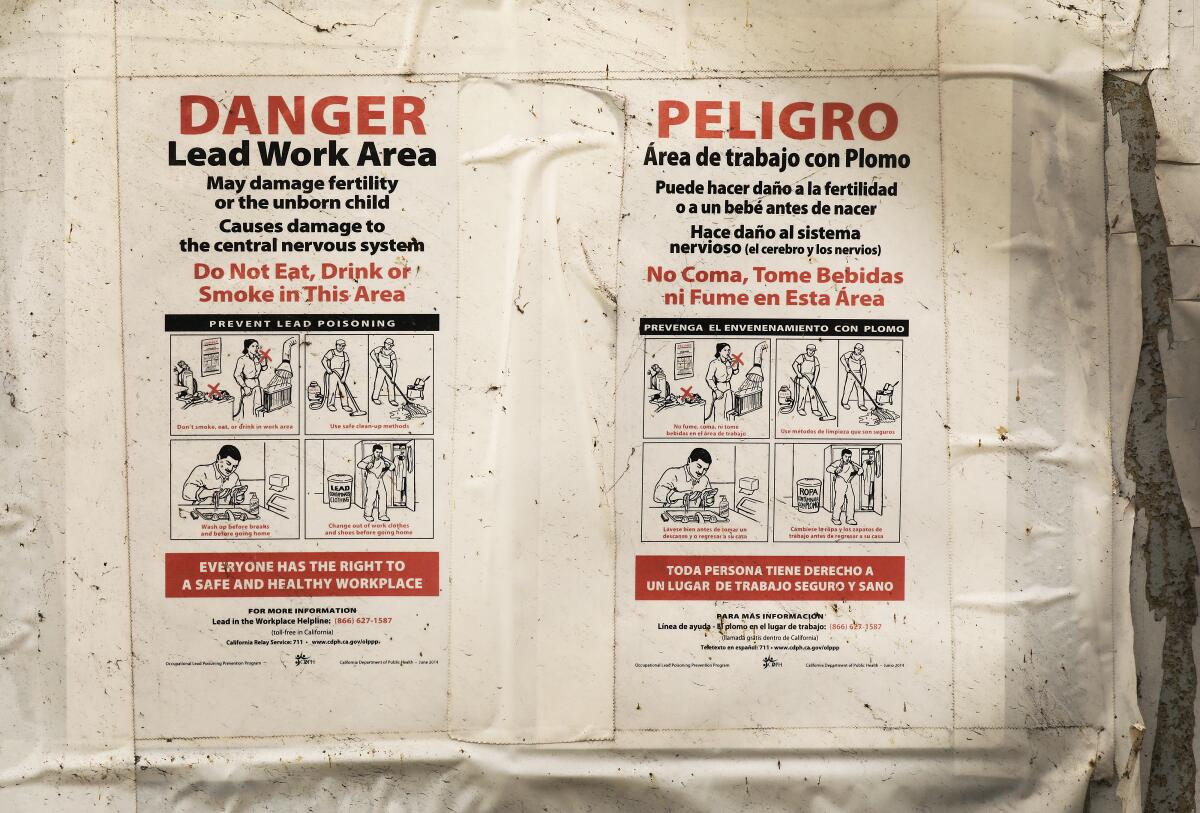

For the first time in decades, California is tightening its rules on workplace exposure to lead, a poisonous metal that can wreak havoc throughout the body.

Experts said the new regulations will make California a national leader in battling the insidious and deadly effects of lead in the workplace.

The California Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board voted 5 to 2 on Thursday to adopt the rules over the objections of business groups that said they were unworkable and difficult to understand.

“The evidence is undeniable that even small levels of exposure can have very, very serious effects,” board member Joseph M. Alioto Jr. said before voting in favor of updating the regulations.

The evidence is undeniable that even small levels of exposure can have very, very serious effects.

— Joseph M. Alito Jr., member of the California Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board

Backers said the stricter requirements were needed in light of evidence that workers could suffer health hazards such as kidney dysfunction or hypertension from amounts of lead well below what California had allowed.

Failing to act on that scientific evidence until now “means that an unknown number of lead-exposed workers have died early from heart disease” or suffered other harm, said Barbara Materna, former chief of occupational health at the California Department of Public Health. “We cannot allow more decades to pass before we take a step forward.”

The new standards are intended to keep lead levels in the blood below 10 micrograms per deciliter, rather than their previously stated target of 40 micrograms, according to Cal/OSHA.

The regulations will go into effect in January, with an additional year for businesses to implement some of the requirements.

The vote comes more than a decade after the state public health department recommended that workplace regulators revisit their lead rules to better protect workers. The existing limits in California are the same as those in the federal standard, but public health officials said they were based on scientific findings that are now more than four decades old.

“The standard became outdated as our knowledge of the harms associated with lower levels of lead exposure developed,” said Dr. Michael Kosnett, a medical toxicologist with the Colorado School of Public Health.

Numerous homes that underwent remediation have been left with lead concentrations in excess of state health standards, according to USC researchers.

Inside the human body, lead acts like a doppelganger for calcium and disrupts important molecular functions when it takes the mineral’s place, said Dr. Howard Hu, a preventive medicine specialist at USC.

Lead “accelerates a lot of the aging-related processes in the body,” ramping up the risk of heart attacks, Hu said. And in the brain, it meddles with connections between brain cells, resulting in “fuzzy thinking.”

The dangers to babies and young children are widely known and particularly dire — including slowed development and learning problems — but adults can be jeopardized as well.

Though lead can kill people within days in high enough doses, it’s often a more pernicious menace, slowly damaging the brain, heart, kidneys and other bodily systems over years and even decades. It can lead to impotence and sterility in men and threaten a fetus if a pregnant person is exposed.

Workers may not know their health has been affected by lead, but it “winds up settling into bones and slowly leaches out over the course of a lifetime,” said Dr. Robert Blink, past president of the Western Occupational & Environmental Medical Assn. As it does, “it causes heart disease, kidney disease, strokes and early death.”

The new rules slash the limit for lead exposure in the air, reducing it from 50 micrograms to 10 micrograms per cubic meter for most workers.

The rules also lower the “action level” — a trigger for making workplaces take steps such as regularly testing blood lead levels — from 30 micrograms to 2 micrograms per cubic meter of air.

Employers are supposed to change their workplace setups and procedures to bring down airborne exposure as much as is feasible. But if measures such as improving ventilation and dust control don’t get lead levels below the state limit, employees must be protected with respirators as well.

Lead can be a hazard for a range of workers, including laborers involved in recycling or manufacturing lead acid batteries; construction workers who do abrasive blasting, steel welding or lead abatement; and employees at firing ranges.

Under California’s existing rules, if a worker reaches a high enough level of lead in their blood, they must be temporarily removed from work that causes exposure and provided medical exams or further testing, all without losing their earnings or other employment rights. The new requirements lower the bar for taking such action.

The Prospering Backyards project brings together scientists, artists, activists and community members to tackle an environmental disaster that has quietly festered for decades.

Industry groups pushed for the state to take another pass at updating the rules, saying the plan was unreasonable and unclear. Many argued that facilities that followed the old rules on airborne lead could keep their workers’ blood lead levels under the targeted level.

The rules “are going to be incredibly onerous and expensive for the industry — ours and many other industries,” said Roger Miksad, president and executive director of Battery Council International, a trade association representing battery manufacturers and recyclers. “You can achieve those blood [lead levels] without draconian changes to air lead requirements.”

Marc Connerly, executive director of the Roofing Contractors Assn. of California, said the new trigger for employers to take action is “so unreasonably low” that many companies will not understand the justification for the stricter requirements and are “just going to thumb their noses at it.”

Board member Chris Laszcz-Davis, who voted against the new rules, raised concerns about whether they were understandable or enforceable. “If we’re going to put a standard out there where everybody scratches their head and says, ‘Here we go again,’ we’re going to see noncompliance,” she said.

Environmental and occupational safety advocates rejected the idea that the new limit on airborne lead was unnecessary. The California Department of Public Health identified more than 2,100 workers between 2019 and 2022 with blood lead levels higher than the new rules are intended to allow — more than 5% of those who were tested.

Those numbers are “telling us that some people are being overexposed,” said Rania Sabty, an environmental health scientist. Limiting lead levels in the air is important because “in public health, we prevent exposure at the source from the start. We don’t wait for it to harm the body and then go and try to do something about it.”

The new regulations set higher allowable limits for airborne lead for some processes used to manufacture and recycle lead acid batteries. Even in those instances, employers are supposed to keep lead exposure under the 10 micrograms-per-cubic-meter limit by using respirators to protect workers.

State regulators estimated the new rules would save $37.9 million in the first year alone by reducing costs associated with lead-related illness and premature deaths. Annual savings are projected to rise each year, reaching $1.7 billion after 45 years. Cal/OSHA officials said clamping down on lead for workers will have a beneficial ripple effect on others, including reducing exposure for children when adults accidentally bring lead dust into their homes.

Complying with the new rules is estimated to cost private businesses roughly $230 million a year, including expenses for medical surveillance, air monitoring and personal protective equipment, according to regulators. Industry representatives disputed that estimate, saying costs had been drastically underestimated and that small businesses would be walloped by the added expense.

Results of newly mandated testing reveal that nearly 1,700 child-care centers across the state have dangerous levels of lead in their drinking water.

Lead exposure for the average person in the U.S. has plummeted since the 1970s as the metal was removed from gasoline, house paint and other common items. But even as that progress was being made, scientists learned that lead can be dangerous at lower levels than previously understood, Hu said.

“There’s no level of lead exposure that is known to be safe, especially for children,” Blink said.

Even if the new rules succeed in keeping workers’ blood lead levels below the state target, they may still be at risk for hypertension, increased blood pressure and decreased kidney function at lower levels, scientists have found. The state public health department had recommended a much lower limit on airborne lead than the one approved Thursday.

Cal/OSHA staff members said they considered a stricter limit but decided against it because the costs for businesses would be much higher and the added benefits were unclear.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.