City’s lawsuit seeks to shift blame over release of LAPD undercover officer photos

In an increasingly tangled legal battle over the publication of LAPD officers’ photos on a police watchdog website last year, the city of Los Angeles has taken new legal action against the journalist and activist group that obtained the images through a public records request.

The move follows several hundred city police officers’ suing the city in a case that seeks damages for the “negligent, improper and malicious” release of the photos, which totaled more than 9,300 images, including some officers said to work undercover.

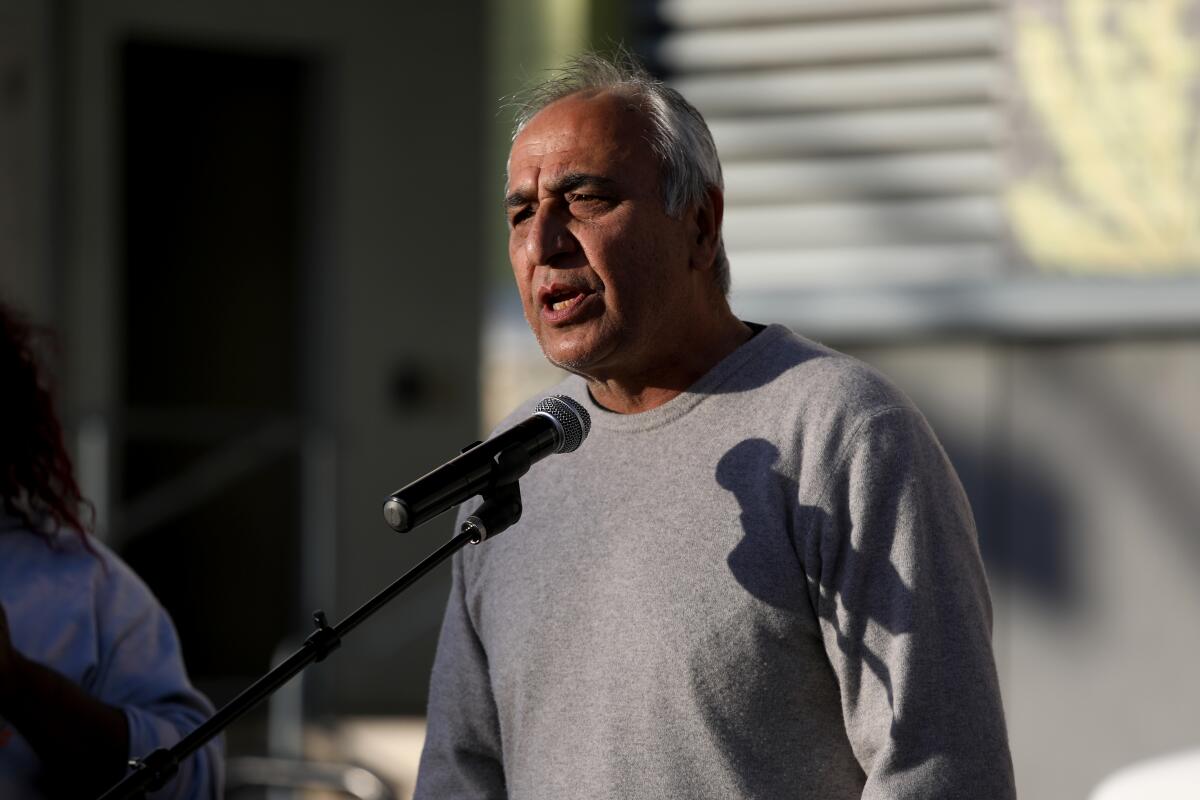

Now, the city is pointing blame at Ben Camacho, a reporter with Knock LA who published the photos with the help of the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, a group that advocates for the abolition of police. Attorneys for the city argue that Camacho and the group ultimately share financial liability for any problems caused by making the images public.

The city previously sued Camacho and the coalition in an effort to claw back the photos, a case that has been roundly condemned by free-speech advocates. Both sides have sought dismissal of the lawsuits against them under a state law enacted to quash frivolous litigation, a legal tactic known as an anti-SLAPP motion, which could force the losing side to pay legal fees.

Shakeer Rahman, who is representing Stop LAPD Spying, characterized the city’s latest filings as an attempt to deflect blame for a situation of its own making.

“I think it’s kind of nuts that on the one hand they say, ‘No, the public can’t be sharing this information,’” Rahman said. Many details about officers were already in the public domain, Rahman added, likening the officer photos to the release by the city controller’s office of payroll data for all city employees, including police officers.

A spokesperson for the city attorney’s office said the office had no comment on the matter.

The legal drama dates back to March, when Stop LAPD Spying turned the photos Camacho received from the city into a searchable database called “Watch the Watchers,” which includes each officer’s name, ethnicity, rank, date of hire, salary, badge number and photo. Shortly after the site went live, LAPD officials said they had erred in releasing photos of officers who worked undercover.

Since then, the case has sprawled in several directions.

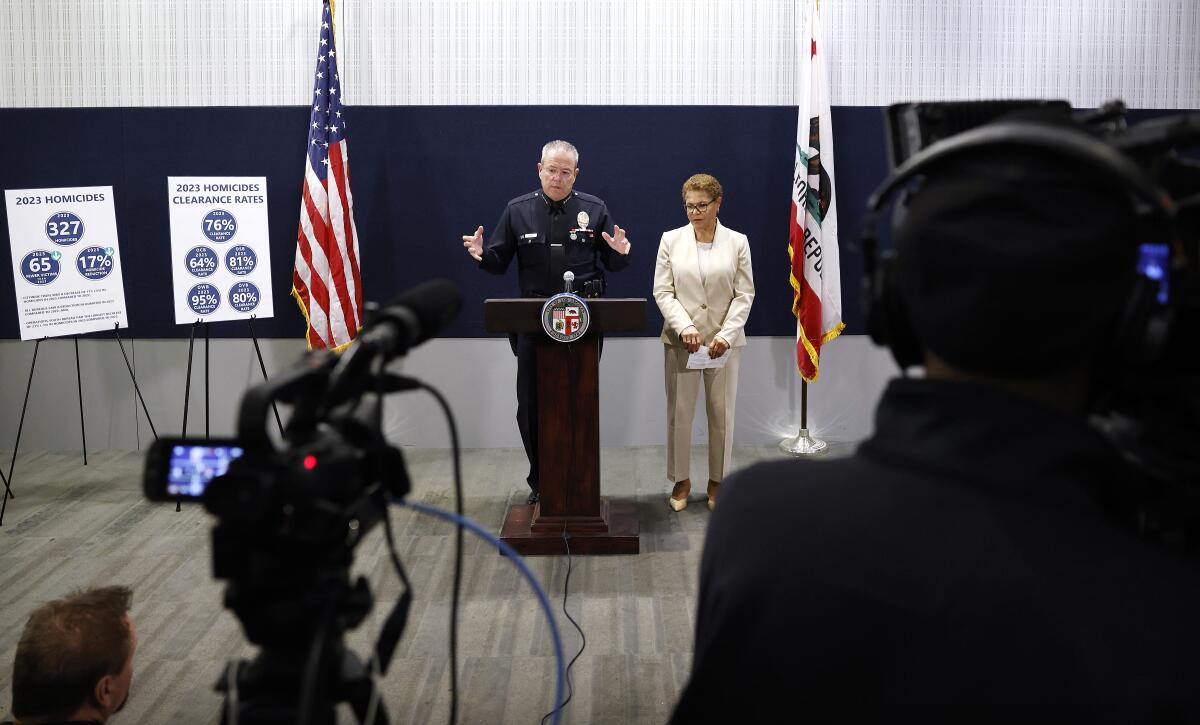

In addition to lawsuits by the city and the officers, the police union has sued Chief Michel Moore. The officers allege negligence, invasion of privacy and breach of contract. The city’s counter-complaint filed last week denied those claims by the officers, who are listed as John Does and number in the hundreds, and named Camacho and Stop LAPD as cross-defendants.

The Los Angeles Police Protective League encouraged LAPD police Chief Michel Moore to respond more decisively to the release of thousands of police officer photos, according to newly-released emails.

The city said it sought “indemnity and contribution” from Camacho and Stop LAPD. In its anti-SLAPP motion filed Jan. 16, the city called the release of the photos an “inadvertent production,” which, “while regrettable, is not actionable.”

Officers who have signed on to the legal challenge against the city have argued the release put scores of LAPD employees in harm’s way, particularly those working in sensitive assignments who have to go to great lengths to disguise their identities.

Officials have spoken broadly about how the photos’ release has affected LAPD operations, without providing specific details. Los Angeles City Atty. Hydee Feldstein Soto, whose office is representing the city in its legal battle, said in a community meeting on Zoom last year that she was forced to rely on federal agents, instead of LAPD officers, to go undercover in prostitution stings.

An attorney for some of the suing officers said last year that several undercover operations had folded because of the photos. He also said LAPD supervisors told him that several undercover officers had been threatened, but declined to provide further details. The city also sued the owner of a social media account that featured posts offering bounties on the lives of LAPD officers.

The lawsuits caught the attention of local 1st Amendment advocates and journalism groups, who banded together to back Camacho and denounce the city’s actions as a brazen attack on protected newsgathering activity at a time when press freedoms were being threatened across the country. The Los Angeles Times was among the outlets to join the coalition against the lawsuit.

David Loy, legal director for the 1st Amendment Coalition, said protections for journalists who publish legally obtained materials are clearly spelled out in the Constitution. He said this was the first time he had heard of a counter-complaint “applied in this context.”

“That might make sense in a multi-car pileup case or a legal dispute,” said Loy. “But it has absolutely no place in a 1st Amendment context.”

He noted that attorneys for the LAPD officers have not tried to sue Camacho or Stop LAPD directly, despite the city’s effort to shift responsibility to them.

“It sends, I think, exactly the wrong message to the press or the public that if you exercise your 1st Amendment rights and we get sued, then we’re gonna come after you,” Loy said.

In August, a judge ruled that the city could justifiably censor the free speech of Stop LAPD by forcing it to stop publishing pictures of officers online. Stop LAPD and Camacho have appealed the decision, which legal experts have described as unusual.

A California judge said the city of Los Angeles could justifiably force an activist group to stop publishing pictures of LAPD officers online.

Hamid Khan, an organizer with Stop LAPD, said the escalating rhetoric by city and police leaders on the danger posed by the photos has been nothing more than a “political play to water down the right of the public to get this public information.”

“They kind of have just demonized us all along the way, which completely goes against the very grain of what public records is,” he said.

Watch the Watchers was originally launched as a public service for bringing more transparency to one of the city’s most powerful institutions, he said. Already, the site had drawn interest from other watchdog groups as far away as Seattle and Wales, as well as some closer to home, Khan said.

“People want to do something on the [Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department], people want to do something in Torrance, people want to do something in Pasadena,” he said.

In a statement, Camacho said the latest court filings were a sign that the city attorney, Hydee Feldstein Soto, “has chosen to further her attack on press freedom.”

“At a time when the future of local media is threatened, Soto has chosen to push her boot down again on the First Amendment,” the statement said.

Shortly after news of the photo disclosure broke last March, Moore ordered an internal investigation. LAPD spokeswoman Capt. Kelly Muniz said in a text message that the probe is ongoing. Once it is completed, she said, the public “would only be entitled to what the Police Commission publishes.”

A separate investigation by the LAPD inspector general’s office concluded late last year, and its findings have been turned over to the Police Commission for a final disposition, according to a spokeswoman for the office.

For all the gains women in the LAPD have made in recent decades, they remain underrepresented in the upper reaches of the department.

Moore, who plans to retire at the end of this month, said he has taken steps to address the safety concerns of officers whose photos were released.

Mayor Karen Bass, who will work with the Police Commission to select Moore’s replacement, has also decried the release of information about undercover officers. She briefly touched on the episode in her State of the City address last year, saying she was concerned that it would “cause even more officers to leave” the already depleted police force.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.