As LAUSD enrollment plunges, only one school is overcrowded. Proposed fixes panic parents

In the deep northwest reach of Los Angeles Unified, tucked among foothills carpeted with newish subdivisions, Porter Ranch Community School has a rare problem. At a time of declining public school enrollment in L.A. and throughout the state, this campus is overcrowded — the only one in the nation’s second-largest school district that is full and turning away families.

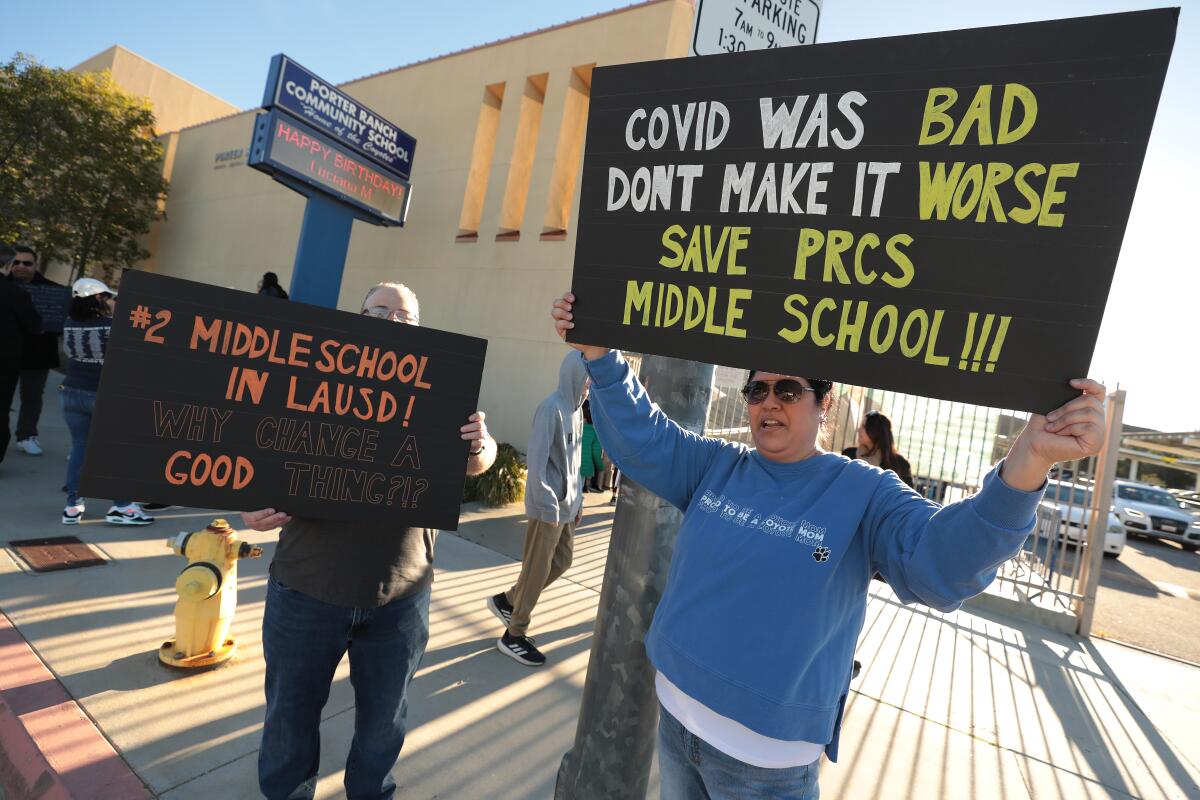

Angry parents of the combined elementary and middle school worry that one proposed solution would break up a community they cherish and also one that they dearly paid for — through home prices they believe are boosted by the lure of its neighborhood school. One plan that was under consideration in recent months calls for lopping off the middle school, grades 6, 7 and 8, and sending those students to an under-enrolled high school nearby.

On Monday, about 200 people demonstrated outside the school — a group that included parents and students who boycotted classes for the day. They spoke of how their community would be sundered and friendships lost, because their public school is at the center of these bonds. Monday evening, families returned to the campus for a meeting with officials, demanding that LAUSD save a thriving, popular school. About 275 people attended in person; an additional 340 households watched on Zoom.

“We just found out that LAUSD wants to move our children to a different campus, and they don’t have a real solution,” said Ani Shahbaz at the morning demonstration. She has a seventh-grade boy and third-grade girl at Porter Ranch Community School. “And so, right now, we are just here trying to make our voices heard, because this is a community and we don’t want the middle school to close.”

L.A. Unified, whose enrollment is expected to plunge by nearly 30% over the next decade, has virtually unlimited classroom space in general, but not in Porter Ranch. School districts throughout the state — including Pasadena and Hacienda La Puente and in Orange County — have closed campuses amid more than five years of enrollment declines.

The enrollment drops will reshape the nation’s second-largest school system and officials said tough choices are ahead.

The Porter Ranch panic began in earnest, said parents, after an October “coffee with the principal” at which Principal Avak Demirjie alluded to the need to resolve the crowding. Some participants thought they heard a reference to moving or closing the middle school, which to them is pretty much the same thing. Fears rapidly spread.

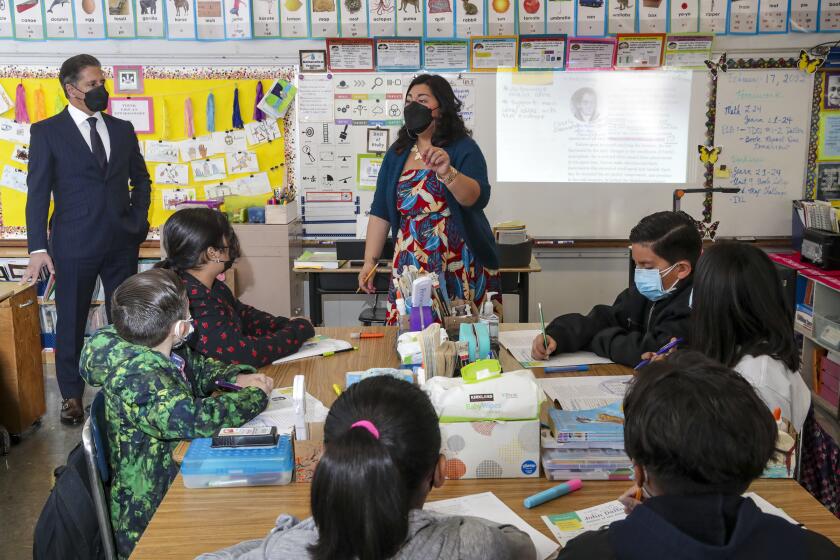

In recent days, district officials have rushed out messages of reassurance, including from Region North Supt. David Baca, who heads one of the four areas into which L.A. Unified is divided.

“Enrollment has grown and we’re in a place of considering all options, but our goal is that we’re going to take additional time to further engage with the Porter Ranch school community and provide the options that will best support students, families and the whole school community,” Baca said in an interview.

Baca and other officials tried to reassure families at the meeting Monday night. They pledged there would be no changes for the 2024-25 school year, but the situation is challenging.

Enrollment has reached the school’s capacity of 1,400 students, and 70 neighborhood students this year had to be turned away. Builders continue to sell homes — with the school as an attraction.

“They’re still selling the school, knowing we’re overcrowded,” said parent Christy Rose, who visited a developer’s model home to hear the sales pitch.

It wasn’t all that long ago that many current school families heard that same promise.

“They’ve been selling the dream,” Shahbaz said. “Your kid can walk to this great school. This is the reason why we all moved here because we had an actual LAUSD school that starts at [transitional kindergarten] through eighth grade and middle school is really difficult.”

An unresolved question is the extent to which developers and L.A. Unified bear responsibility for the logjam. Developers pay fees to offset the impact of their projects. Sometimes they set aside land for schools — as happened with the existing Porter Ranch campus. Sometimes they set aside land only after pressure from the school district and other local officials.

It’s not yet clear what developers offered or delivered as thousands of homes were built in recent decades on one of the last significant swaths of open land in Los Angeles. It’s also unclear how L.A. Unified managed the developer fees.

L.A. City Councilman John Lee, who represents the area, said the basic development plan has been in place since the 1980s and is largely complete.

But the facts on the ground have changed in small but significant ways. The district expanded the school to include grades 7 and 8, for example. And recently added the new grade of transitional kindergarten for 4-year-olds, part of a statewide expansion of early education.

As transitional kindergarten expands across the state, California’s child-care industry is left scrambling to fill empty spots they once depended on.

The Porter Ranch campus, opened in 2012, is one of the newer L.A. Unified schools. Initially, the campus was under-enrolled — and therefore open to families from outside the area. But at the time, the surrounding community still was under construction. The school sits among rolling foothills that have become seas of red-tile-roof stucco homes in a succession of gated communities. Down the hill this new expanse of suburban L.A. offers retail centers with large parking lots dotted with trees too small to give shade.

But what it lacks in settled charm, it makes up for in community.

“We are a town because of this school,” said Adrienne Masi, whose seventh-grade daughter has attended the school since it opened. “Because you can go to the market and see somebody you know. Your kids can play with each other. People are best friends.”

“We all look out for each other,” Rose said. “I can’t tell you how many times there’s been situations where kids were left alone and parents will stay until that parent comes to pick him up. You don’t get that anywhere else.”

A solution opposed by many parents calls for moving the middle school to Chatsworth High School, which is 4.5 miles and a 10-minute drive away. That school’s enrollment has trended the opposite way. When the Porter Ranch school opened in 2012, it had 719 students; the high school had 2,495 students.

Teaching of cursive writing returns after falling to the wayside amid revised learning standards and emphasis on keyboarding. Backers say it promotes learning.

The Porter Ranch school has since doubled in size, while the high school is about half as large as it was about 20 years ago. Porter Ranch feeds into Chatsworth High, but its students don’t necessarily attend the school. They fan out instead to high schools, magnet programs, charter schools and private schools across the Valley. The high school has about 1,700 students and space to spare.

Many parents see Chatsworth High as a poor fit — and question the academic rigor. About 40% of Chatsworth High students met or exceeded state standards in English language arts and literacy; about 23% in math. At the Porter Ranch school, about 77% of students met or exceeded standards in English and 69% in math.

“My child is going to be displaced after fifth grade?” parent Sheena Thakur asked. “Why would you go to Chatsworth? Our median home price over here in Porter Ranch is like $1.2 million, right? So our taxes are that high. What do we pay our taxes for? So that we have this great community school to come to.”

Porter Ranch Community School is ethnically and culturally diverse, but notably less present — compared with Chatsworth High — are low-income families. At Porter Ranch, 18% of students qualify for a free- and reduced-price lunch; at Chatsworth, 68.5%. At L.A. Unified overall, the figure is 81%.

Porter Ranch parents said they are concerned about their middle school students sharing a high school campus, especially one that also houses a continuation school, which serves students who fared poorly in a traditional high school.

“I’m a part of the movement of trying to make Chatsworth High better,” said parent Juli Little, who has four students at Porter Ranch. “I have my ninth-grader at the Chatsworth High magnet school. But do I want my middle schoolers on a high school campus? Absolutely no way.”

At the Monday meeting, every time Baca mentioned the possibility of a move to Chatsworth High, the audience roundly booed.

Parents said they are open to various potential solutions, including putting portable classrooms on the campus. Many also would support sacrificing all or part of a local park for school space. Councilman Lee, however, said state law would not permit such a change of use. There also was talk of changing attendance boundaries so the buyers of new homes would not keep adding to the school’s burden.

Parents were told that about 63 students from outside the neighborhood attend the school on a permit — and that no new permits would be approved.

“When you have a school that is so desirable that everyone wants to go there, that’s a good problem,” Baca told parents in trying to hit a positive note and find the right tone. When an angry rumble ensued, he quickly, diplomatically changed tack. “Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean there’s a shortage of strong feelings, right?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.