The 1994 Northridge quake was a shock. Here’s why the next one won’t be

Susan Hough remembers the violent shaking that jolted her and millions of other Southern Californians awake just after 4:30 a.m. 30 years ago.

“It was like a giant picked up my house and started shaking it back and forth in his fist,” said Hough, a geophysicist for the U.S. Geological Survey. She thought she heard glass breaking in her Pasadena home, “but when the dust settled, there were no broken windows and no broken furniture.”

Many others were not so fortunate. The 6.7 magnitude quake centered in Northridge resulted in more than 9,000 injuries, 60 fatalities and up to $20 billion in property damage, plus $40 billion in economic losses, according to the California Department of Conservation.

Scenes of devastation could be found across the city. A stretch of the 10 Freeway at La Cienega and Washington boulevards collapsed. A three-story Northridge apartment became a crumpled heap. Ruptured gas lines and propane tanks sent fiery balls bursting through asphalt roads in a mobile home park in the San Fernando Valley.

Communities were left without power, and the National Guard mobilized to prevent looting in blacked-out neighborhoods. Search-and-rescue missions were conducted for survivors who were stuck under rubble. Hospitals were inundated with the injured.

Since then, however, advances in science and technology have enabled seismologists to track and study quakes more effectively. Those advances don’t negate the risk of destructive earthquakes that cause the sort of devastation seen 30 years ago. But at least we have more tools now to help us prepare for the next big temblor.

Advances in earthquake science

Northridge spurred the development of the ShakeMap, which uses data from sensors to map ground motion and shaking intensity right after a significant earthquake.

These maps are used by local and federal agencies for earthquake response and recovery operations, as well as preparedness exercises and disaster planning. They also provide insights on quakes to researchers and the public.

The rapid feedback provided by ShakeMap stands in sharp contrast to the situation 30 years ago. When the tremor struck Northridge, it took about two months to map the distribution of the ground acceleration that occurred during the shaking, said Lucy Jones, California’s earthquake expert.

Prior to Northridge, the data were recorded on photographic film chips by sensors out in the field. Here’s how the U.S. Geological Survey described the process of gathering and analyzing the data back then: “Drive to the seismic station, retrieve the photographic film, bring it back to the lab, process it. With several earthquake recordings in hand and a ruler, measure the height of the wiggles and the time between the wiggles recorded at each station, and then triangulate on a location.”

The film chips were left behind when sensors arrived that could send an analog signal about seismic activity through a radio. The signal’s information was digitized when it got to a central computer. The computers in Pasadena were so old and slow, Jones said, the USGS had to program them to give the seismic data priority over anything else the machines were doing.

At the time of Northridge, Jones said, she was working with about seven computers out in the field collecting data and information. Now, there are hundreds of digital sensors out in the field.

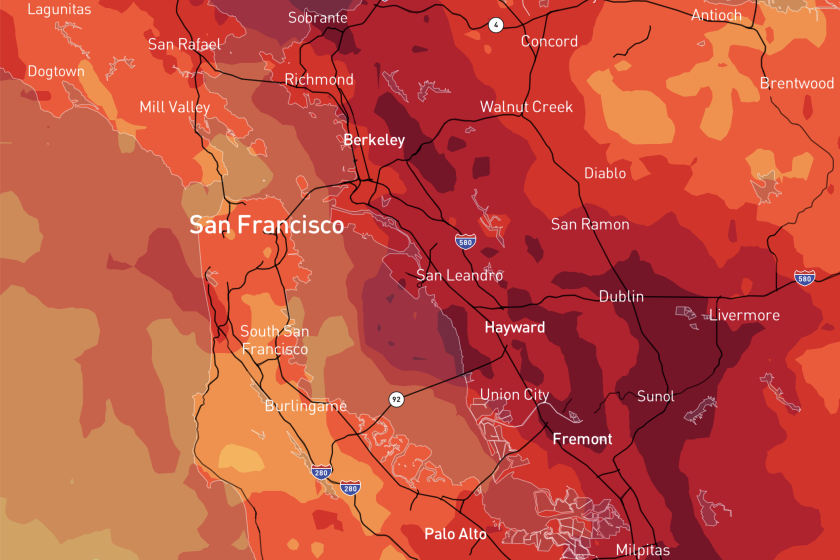

California has suffered some destructive earthquakes in the last few decades but much bigger quakes are possible. These maps show some scenarios.

The rapid ability to collect and analyze the information enables the USGS to disseminate information about quakes faster than the most powerful tremors spread through the ground. The USGS now manages ShakeAlert, an earthquake early warning system designed to give people on the West Coast notice of when a moderate to strong quake hits nearby. The hope is that the system will alert people at least a few seconds before an earthquake’s waves reach their location, giving them time to take shelter.

Whether the alerts reach people in advance, though, depends on how intense the quake is and how far away it starts, the USGS says. It can take time for information to be collected, analyzed and then sent to a person’s phone via earthquake alert, according to USGS. The larger the temblor, the greater the amount of data needed and processed from a number of seismic stations.

Californians have three ways to receive alerts: through text-like wireless emergency alerts on their phones, via the MyShake smartphone app or through Android phones’ built-in earthquake alerts.

Aside from locating the epicenter of a quake, Hough said, the current earthquake monitoring technology is also telling us the distribution of the shaking — how far from the epicenter the shaking occurred and its potential to cause harm there — which is what emergency responders need to know.

“Northridge sparked the development of the modern seismic network in California, essentially, and everything that follows from that,” she said.

It brought together the seismic community that would establish the Southern California Earthquake Center, headquartered at USC, that has been a major partner in risk reduction efforts. It also ushered in the formation of the Advanced National Seismic System and at the regional level, the California Integrated Seismic network.

Preparing for the next shake

When the earth rumbled on Jan. 17, 1994, then-Pasadena resident Robert de Groot said he got under a doorway.

“I realized later, that wasn’t quite the right thing [to do],” said de Groot, USGS’s ShakeAlert coordinator.

After Northridge, he said, scientists and emergency coordinators were motivated to revisit how to prepare and respond to such disasters.

One effort was completing the earthquake catalog that started in 1932. In 2008 a team of scientists led by seismologist Kate Hutton brought the log up to date, with records from almost 600,000 earthquakes, said Egill Hauksson, emeritus research professor of geophysics for Caltech.

Hutton’s catalog is a trusted source and used throughout the world as a database for research to understand earthquakes — their occurrence, the sequence of main shocks and aftershocks, what triggers them, and more, Hauksson said.

Out of different research and preparedness studies came one familiar preparedness program: the Great ShakeOut earthquake drills, which launched in 2008. The exercises have been teaching students, workers and people at home to drop, cover and hold on during a large tremor.

“We now have very concrete steps we can do to protect ourselves not only before the earthquake, to get ready for that earthquake, what to do during [and] also how to recover from those events after it’s over,” he said.

Unshaken is the L.A. Times newsletter guide to earthquake readiness and resilience. Sign up for this six-week course to get you ready for a major earthquake in California.

Preparation doesn’t just come in the form of a memorized plan and packed kit, but also in future-proofing your home.

In 2013, the state started offering grants to help homeowners retrofit older homes in areas at high risk of temblors. Dubbed “Earthquake Brace + Bolt,” the program covers much or all of the cost of bolting a house to its foundation and bracing the studs holding up the ground floor.

State officials just announced that the program was expanding the availability by almost 60%, increasing the number of eligible ZIP Codes to 815 (including much of Los Angeles County). The program’s basic grant covers up to $3,000 of the cost of a newly completed retrofit on a house built before 1980 with a raised foundation.

Households with incomes below $87,360 can qualify for an additional grant that could cover the entire cost of a retrofit, according to the program’s website. The supplemental grant for bracing and bolting a home is $7,000 in Northern California, $2,650 in Southern California; smaller amounts are available for bolting only.

The program, which is overseen by the California Earthquake Authority and the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, says it will accept grant applications on its website through Feb. 21. The grants have helped pay for retrofits at more than 23,000 homes so far, but the earthquake authority estimates that more than 1 million need seismic upgrades.

The state of California also stepped in after insurers sharply cut back on homeowners policies after Northridge, establishing the California Earthquake Authority to offer earthquake coverage. The premiums are significantly higher than what private insurers charged, though, in part because they’re designed to cover the damage even from a historically violent quake. As a result, the authority estimates that only 13% of California homeowners have earthquake insurance.

People are much more important than kits. People will help each other when the power is out or they are thirsty. And people will help a community rebuild and keep Southern California a place we all want to live after a major quake.

The authority has tried to make its policies more affordable by offering more options — for example, allowing homeowners to have separate deductibles for their dwellings and the items in them, such as furniture, appliances and other personal items. In 2023 it also slashed the maximum limit of insurance for personal property from $200,000 to $25,000, eliminated some of the low-deductible options and the optional coverage for breakable items and masonry veneer.

Room for improvement

With important questions still to be answered about earthquakes, scientists are recruiting the public to help gather data about tremors in the region. In 1999 the reporting tool “Did you feel it?” was made available in English so Southern Californians could share their experience of the Northridge quake — where they were, how intense the shaking was, what happened to the items around them during the tremor, and what damage occurred.

The information supplements the readings scientists collected and assists in understanding the effects of past and future earthquakes. Hough said the responses from the questionnaire also help map the severity of earthquake shaking in far more detail.

“There may be thousands of [sensors] in California at this point, but there’s 39 million people and every one of us is a potential human seismometer,” Hough said.

As of Jan. 10, the reporting tool had 9,983 responses, but when looking at the locations generating the reports, she said, scientists realized that they weren’t hearing from all over the battered Southern California region.

USGS has now made the online tool available in Spanish and Chinese, and the agency is again asking the public to log their experiences from 30 years ago. Hough said it’s a step in the right direction to engage a diverse population.

Homes with raised foundations can be susceptible to serious damage in an earthquake. California’s Earthquake Brace + Bolt program can help pay for seismic retrofits.

There’s also work to be done to improve the early warning system and move away from individualized emergency instructions, Jones said.

Japan and Mexico have integrated early warning systems into the fabric of daily life. Japan’s warnings sound from cellphones, televisions and radios. Mexico’s sirens blare moments after a large temblor is detected, aiming to give residents time to seek safety before the shaking reaches them.

In California, by contrast, the system relies on people signing up for alerts — and having a device on hand that can receive them.

The second hurdle, Jones said, is changing how emergency messaging is framed.

“It’s an interesting thing about Americans, that we’re so individualistic that FEMA is convinced that the only messages they can give out are for what an individual can do,” she said.

The guidance, Jones argues, becomes isolating because it’s all about what “you” can do for yourself and family.

“There’s sort of an implication that your neighbor can become your enemy, yet the research shows us that the degree to which a community has high social capital, the degree that people are connected to each other, those are the communities that recover,” she said. “And yet our messaging tends to be divisive.”

Part of a person’s emergency response plan should include their community, community resources, and what can be done for others.

“I think it’s also what really needs to happen for us to get through the next earthquake,” Jones said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.