Compton honors late N.W.A rapper Eazy-E by naming a street after him

Eric Darnell Wright Jr. remembers his father driving down Muriel Avenue in Compton for Thanksgiving dinner.

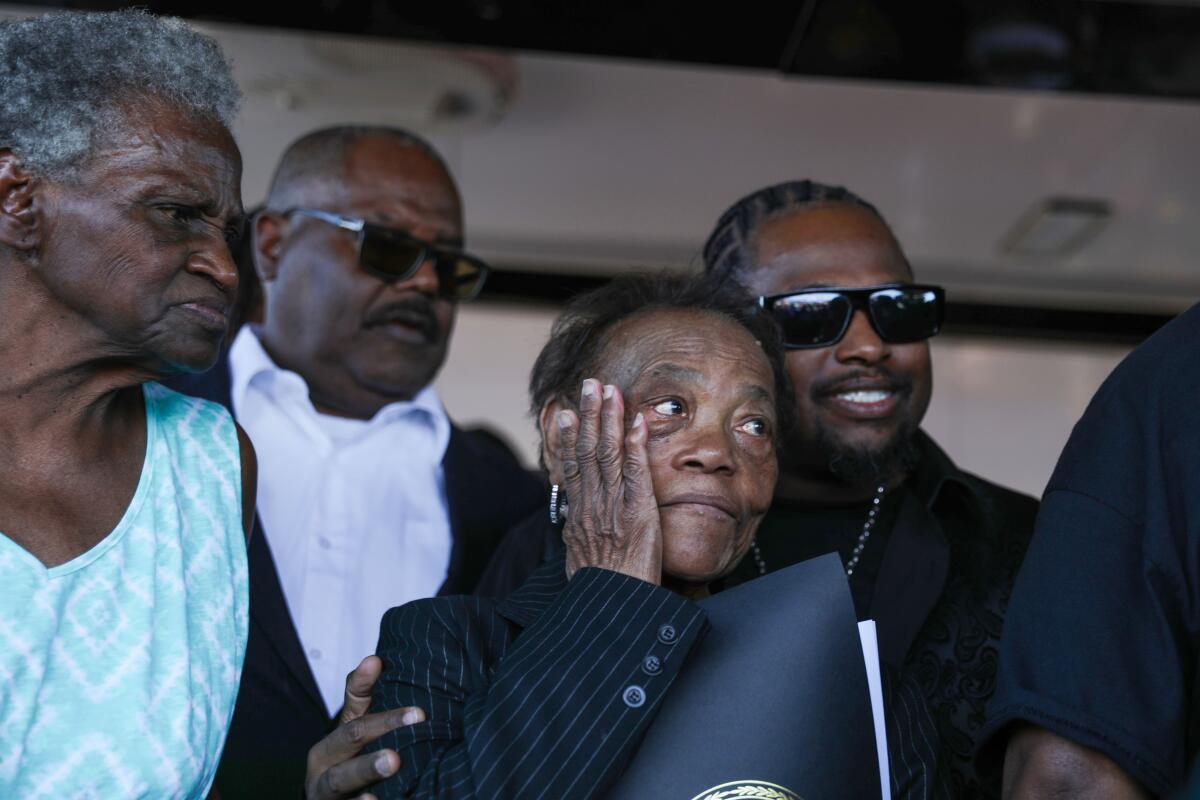

It was there that his now 86-year old grandmother, Katie Wright, would prepare large meals for all her kin, including her son Eric Lynn Wright — better known as the late N.W.A rapper Eazy-E.

“It wasn’t no entertainment,” Eric Darnell Wright, the rapper’s son who goes by Lil Eazy-E, recalled. Only family existed in these moments. “It was just kind of like the hip-hop world was out of it.”

Erica Wright, the artist’s oldest daughter, never really cared for the rapper Eazy-E. “I cared about Eric,” she said of her father.

The siblings said they were heartbroken they weren’t able to spend enough of those moments with their dad, who died in 1995 at the age of 31.

On the day of Wright’s funeral, cars rolled down Harvard Boulevard near the First African Methodist Episcopal Church. His gold coffin was wheeled into the church as thousands of people — including fans, family, gang members, mothers and children — watched.

More than a quarter-century later, Wright’s son still remember his father cruising in his “six-four” through the streets of Compton to N.W.A classics like “Straight Outta Compton.”

Decades after Wright and N.W.A helped put the city on the map with the chart-topping single “Boyz N the Hood,” Eazy-E was celebrated Wednesday with an honor befitting someone who loved to cruise down the avenues of his famous and sometimes infamous hometown.

Compton officially renamed Towne Center Drive as “Eazy Street.”

“It’s about time,” a man in the crowd yelled as officials raised the lime green sign for the public to see.

The happy disruption and ceremony featuring lowriders, musical performances and original gangsters in a Best Buy parking lot perfectly encapsulated Wright’s rugged personality, his loved ones said on stage.

Eazy-E’s graphic lyrics from old albums blared from the stage where former N.W.A member DJ Yella exchanged greetings with Wright’s loved ones. Members of Bone Thugs-N-Harmony showed up for the event to pay respects to Wright, who appeared on their track “Foe tha Love of $” the year he died.

Black hats embroidered with “Compton” in bold white letters poked above the hundreds of attendees who danced in the crowd.

1

2

3

4

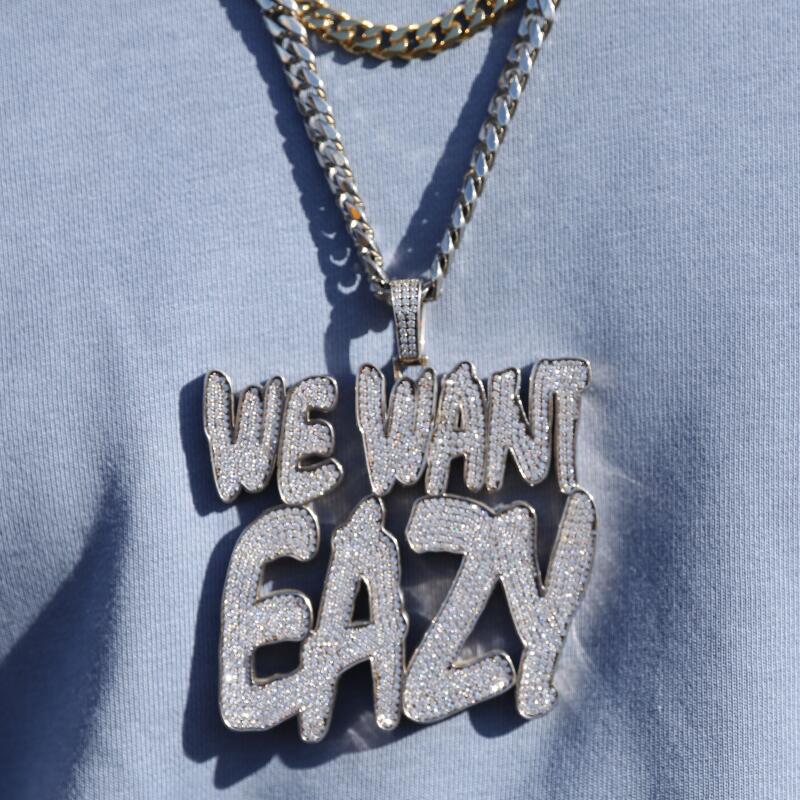

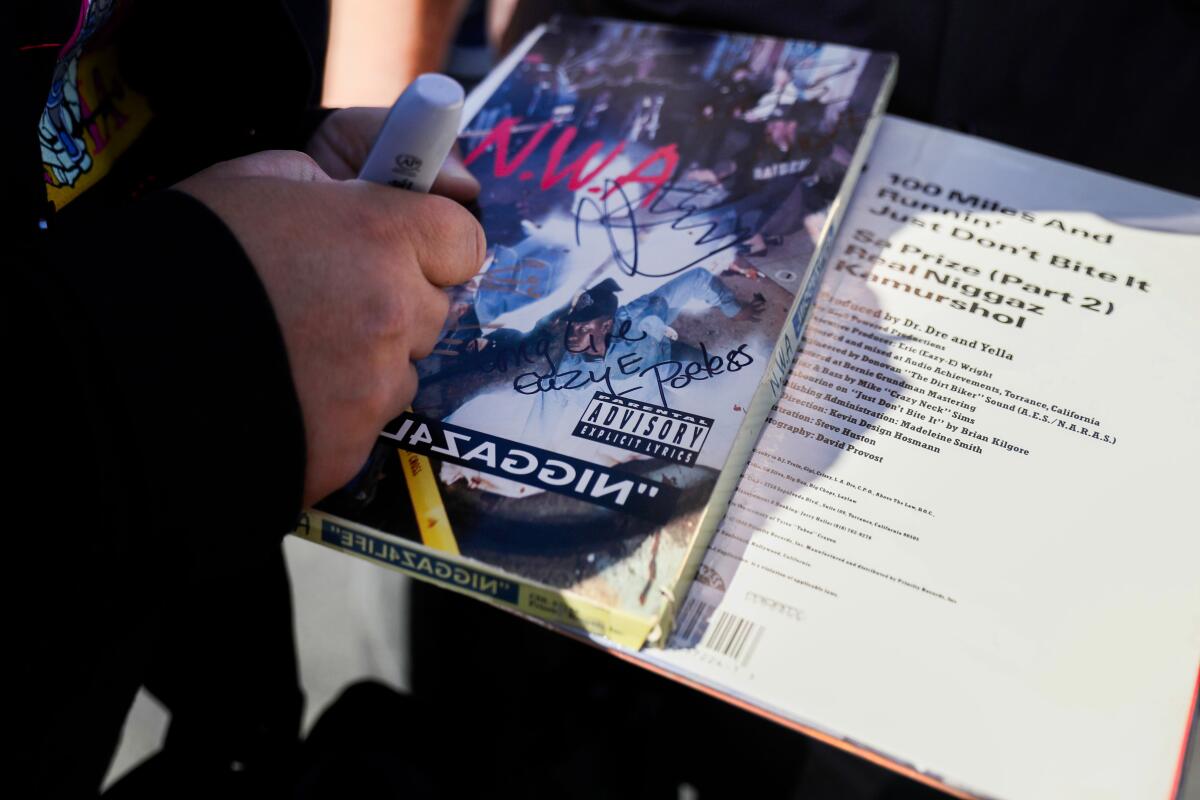

1. An attendee at Wednesday’s ceremony shows his N.W.A tattoo. 2. Another attendee wears a ‘We Want Eazy’ chain. 3. A woman named Bee shows her Eazy-E tattoo while wearing an N.W.A T-shirt. 4. MC Benyad, a member of the group Blood of Abraham that recorded for Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records label, signs N.W.A’s second album for a fan. (Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

With fellow N.W.A members Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, DJ Yella, MC Ren and Arabian Prince, Wright brought notoriety to Compton with the group’s West Coast rap albums.

Before the fame, Wright was a high school dropout who dealt drugs for a living.

Two album releases — N.W.A’s “Straight Outta Compton” and Wright’s solo project “Eazy-Duz-It” — were considered the opening of a new era for hip-hop, a genre and industry that had primarily been lyrically defined and commercially dominated by East Coast acts until that point.

Both albums were released under Wright’s label, Ruthless Records, which he co-founded with manager Jerry Heller.

With iconic music videos showing Eazy-E and his group parading through the streets, Wright, a Compton native, quickly rose to the status of American pop culture icon.

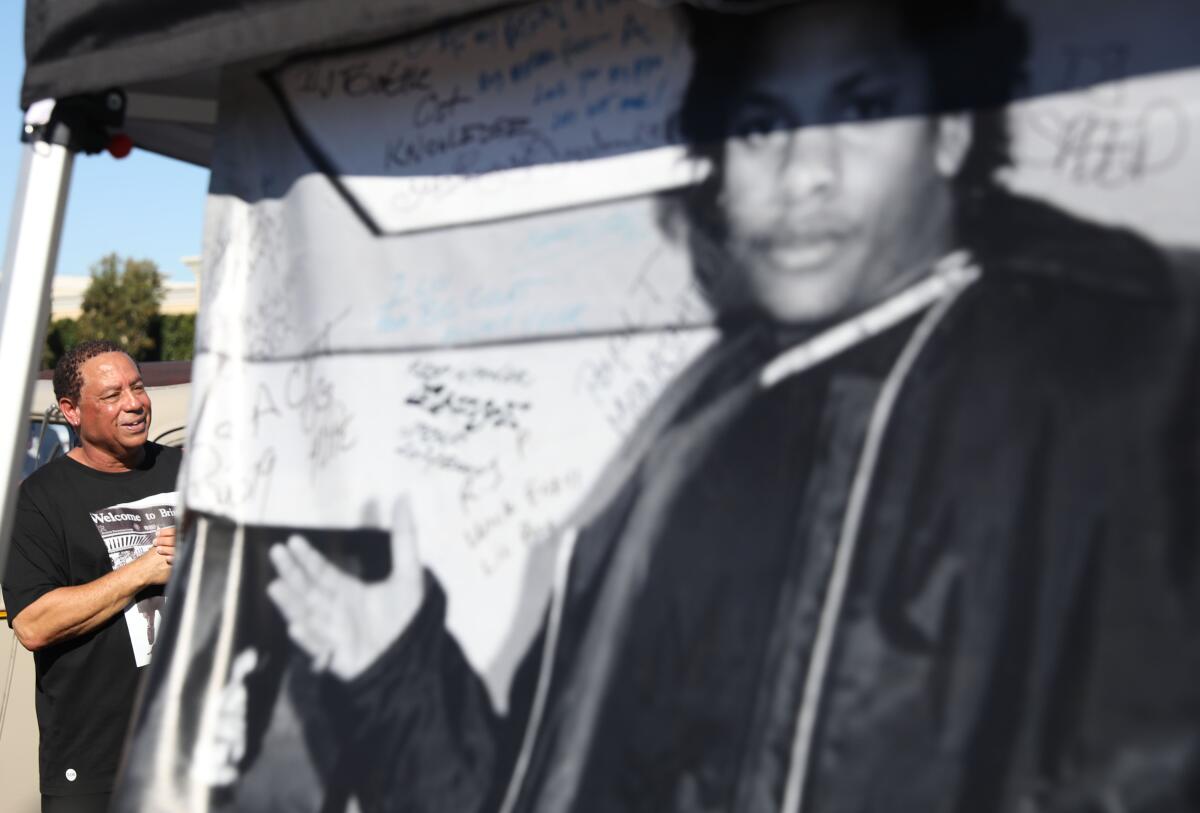

Alonzo Williams — one of Wright’s earliest collaborators — owned Compton’s Eve After Dark nightclub, which helped launch acts including Dr. Dre and Eazy-E. He now heads the Compton Entertainment Chamber of Commerce that organized the event and spearheaded the naming of Eazy Street.

“Always putting in work,” a member of the crowd yelled in recognition of Williams during the event.

Wright went to Williams for advice when setting up Ruthless Records. Williams introduced Wright to a graphic designer and later Heller.

“Eazy was one of the realest cats that I ran into back in the day,” Williams said after a cruise down Eazy Street. “I got a lot of respect for him because no matter how much money he made he stayed true to himself.”

Even after Wright found fame, Williams said, the rapper would often visit him at his garage, where N.W.A. recorded their first songs.

Actually, Wright never wanted to be a rapper, Williams added. But he fell into a character — a crazy 5-foot-4 trash talker — that he created and enjoyed acting out while out on the streets.

Williams remembers asking how long Wright intended to “play the role.”

“As long as they’re buying tickets,” Wright replied, according to Williams.

“The character on stage was one thing, but I knew the man,” Williams said. “He was a fun-loving father.”

“I’m glad to be a part of his entrance into the music game. I’m glad to be part of his legacy,” Williams added.

Gerald “Bop” Payton echoed the sentiment in the parking lot with recording artist Rondevu — who was on the first Ruthless Records album with Eazy-E before he became famous for “Boyz N the Hood,”

Payton, a childhood friend who first met Wright at the age of 10, claimed there are five versions of “Boyz N the Hood,” He’s on one, though it has never been released, he said.

Payton said he was there to witness Eazy-E’s meteoric rise to the top of hip-hop and was at the side of Wright’s hospital bed in 1995. The artist died just days after he announced he had been diagnosed with AIDS.

Wright’s parents, Katie and Richard Wright, were working class, Payton recalled. And the prominent rapper was one of the only children in the neighborhood with both parents at home during a time when Los Angeles and places like Compton were wracked with sky-high murder rates wrought by gang wars.

Payton’s own father, a lieutenant in the Compton Police Department, was one of seven officers living on their block, “so we had to keep everything on the down low.”

Payton said memories of his friend’s first car, first job and mischievous adventures hang in his head like they happened yesterday.

“He used to hate [that] I could finish his sentences,” Payton said. “We always knew what each other was thinking. I might not have thought he was right, but nothing could come between us.”

He and Wright drove around in a Chevrolet El Camino in the 1980s, and took turns playing the role of driver and chauffeur, opening doors and pretending to ask for autographs in order impress young girls in the neighborhood.

The reason Wright was first interested in records “had nothing to do with making money,” Payton said. He was trying to impress a girl.

Early on, Payton said he didn’t think Wright had a future behind the mic. That caused some tension.

“I just couldn’t believe anybody was going to like it. And he didn’t take that well,” Payton recalled.

Looking back at everything his friend accomplished, he added: “This is just another big ‘I told you so’ from him to me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.