A space engineer who brought us images of Mars confronts Earth’s brutal realities in Gaza

From his modest home office in Santa Monica this week, Loay Elbasyouni prepared to review rocket engine designs during a meeting on Blue Moon, a spacecraft that in the not-too-distant future will launch astronauts to the moon to explore the surface of its southern pole.

NASA’s Artemis V mission, scheduled for 2029, is fifth in a planned series of efforts to return to Earth’s lone natural satellite for the first time since the Apollo program. And it’s not Elbasyouni’s first foray into space exploration.

Before his current job as senior manager of engine electrical design for Blue Origin, a space technology company owned by billionaire Jeff Bezos, Elbasyouni helped design a lightweight robotic helicopter for NASA’s Mars 2020 Perseverance Rover mission. Dubbed “Ingenuity,” the aircraft made history in 2021 when it took to the skies above Mars and recorded stunning views of the Red Planet’s rocky terrain during its initial trek.

“One thing that I have learned from space is that Earth is very special place,” said Elbasyouni, 44. “The worst place on Earth is better at sustaining life than the best place on Mars.”

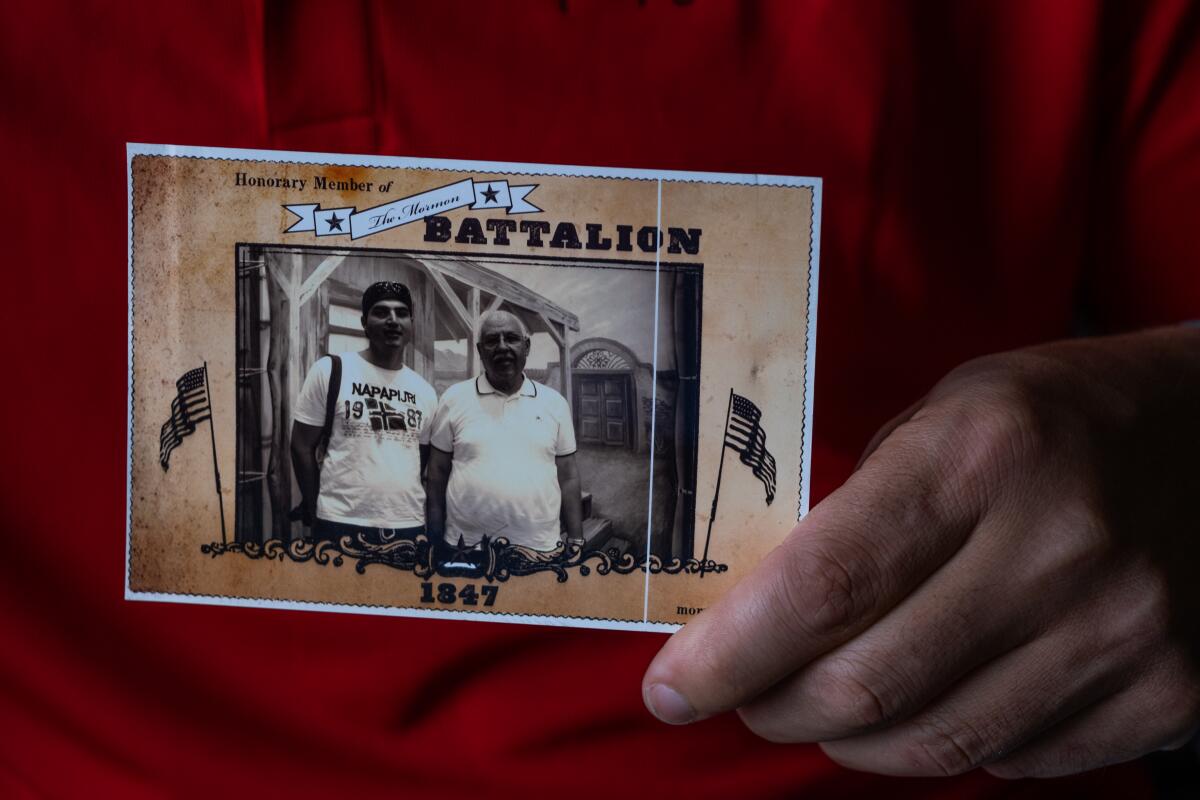

In Elbasyouni’s hometown of Beit Hanoun in Gaza, Ingenuity made him a proud son of Palestine. His image was featured in schools and on banners hung along the main street leading into the city. Elbasyouni’s uncle hosted a grand celebration in Beit Hanoun in honor of his nephew, with a guest list that included the city’s mayor.

“It was a great moment of pride,” Elbasyouni said. “The helicopter flight on Mars probably went more viral in Gaza than anywhere else.”

Those were heady times, before the events of Oct. 7 spawned a crushing war that set Elbasyouni on a more anguishing, terrestrial mission.

A forensic investigator in Tel Aviv works to reassemble remains of victims of Hamas militants, trying to understand the causes of death and the underlying cruelty.

He awoke that day to a flood of text messages. Hamas militants had launched a vicious surprise assault on Israeli civilians in towns and kibbutzim near the Gaza border, slaughtering 1,200 people, most of them civilians. Elbasyouni worried about his parents, Mohammed and Alya, who were visiting Beit Hanoun, a city of 35,000 in northeast Gaza, during an extended stay from their adopted home in Germany.

By the time he reached them by phone, the Israeli Air Force had mounted a counteroffensive that included punishing airstrikes on Beit Hanoun.

“My parents told me there was a bombing on their street,” Elbasyouni said. “After that, I lost communication.”

In the weeks that followed, Israel has largely cut off food, fuel, electricity and water to Gaza. Its army is carrying out a relentless bombing campaign with the stated aim of destroying Hamas hideouts and supply networks. More recently, Israel launched a ground offensive in northern Gaza, with fierce fighting in Beit Hanoun. More than 11,000 Palestinians have been killed in the assaults, according to the Gaza Health Ministry.

In the early days of Israel’s offensive, Elbasyouni’s parents left Beit Hanoun to hole up with dozens of others at a medical clinic in Gaza City that his father, a surgeon by trade, established and still owns. Elbasyouni pushed to get the German government to put his parents, who have German citizenship, on an emergency evacuation list to get them out of Gaza.

They remain marooned there, despite his best efforts.

With Mohammed, 75, hampered by a recent back surgery and Alya, 68, suffering from a bad hip, asking them to walk 20 miles to the otherwise shuttered Rafah border crossing into Egypt to plead for safe passage is out of the question.

“My father told me he would rather die where he is,” Elbasyouni said.

A towering figure with wooly, short-cropped hair, Elbasyouni wore a NASA polo shirt with an image of Ingenuity embroidered on its left pocket as he recounted his family’s roots in Gaza over lunch at a Palestinian-owned restaurant in downtown Los Angeles.

Mohammed, his father, was born in Gaza’s Jabalia refugee camp in 1948, the same year Israel became an independent state in what Palestinians call the “Nakba” or catastrophe. An Israeli strike on the camp left week-old Mohammed injured with a shrapnel wound.

“My grandmother thought he was dead,” Elbasyouni said. “My family left him when the bombing happened, but then they heard his cries, went back and got him.”

Elbasyouni was born in a suburb near Frankfurt, Germany, while his father was studying medicine. But he spent his formative years in Beit Hanoun after Israeli authorities suspended his father’s passport during a visit to Gaza in 1984.

Growing up in a heavily guarded border town, Elbasyouni felt the menace of occupation. He recalls a time he was walking to a United Nations school he attended with his brothers, when schoolchildren suddenly dashed into a house. Elbasyouni followed, but didn’t know why until he peeked through a crack in the door and saw an Israeli military jeep pass by with a soldier holding a machine gun.

Elbasyouni remembers fleeing soldiers another time amid a burning fog of tear gas at his school. That was well into the Palestinian uprising that began in 1987, known as the first intifada. Some classmates hurled rocks at Israeli military jeeps, while he and others ran. In the fracas, Elbasyouni said he saw a classmate get shot in the back.

He channeled those harrowing experiences into art projects that also hinted at his future in engineering.

Elbasyouni cranked his hands to show how he used to turn circular knafeh dessert trays into clocks as a teenager. He keeps pictures of the makeshift clocks on his phone, including one decorated with the fishnet design typically embroidered on Palestinian keffiyeh scarves.

When stargazing from Gaza’s beaches, Elbasyouni imagined reaching for the cosmos. “I actually wanted to fly the space shuttle,” he said. “I just loved anything fast.”

His father pledged to support Elbasyouni’s education abroad with money the family made from groves of lemon, orange and olive trees in Beit Hanoun.

Elbasyouni emigrated to the U.S. in 1998 on a student visa and attended the University of Pennsylvania. He continued his studies in Kentucky, at the University of Kentucky and then University of Louisville, and worked as a pizza deliveryman to help with tuition. He said covering expenses became more challenging after Israeli tanks bulldozed his family’s groves in Gaza.

A month after the 9/11 attacks, he was called to a late-night pizza delivery at a University of Kentucky dorm. A group of men hurled expletives along with shouts of “Arab, go home,” he said, then beat him. The incident was investigated as a hate crime.

After graduating with a master’s in engineering from Louisville, Elbasyouni believed technology could help heal humanity’s relationship with the environment, if not its internal strife. For many years, he took jobs working on electric vehicles and wind energy.

Then came an opportunity to work with NASA on Ingenuity at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, setting him on a trajectory into the cosmos.

“Mars was considered mission impossible,” Elbasyouni said. “And then we achieved it!”

In the early morning hours of April 19, 2021, Elbasyouni watched NASA TV from his home amid COVID-19 restrictions that didn’t damper his excitement.

As lightweight as a laptop and designed without a single screw, Ingenuity boasted two rotors capable of 2,400 rotations per minute, a speed needed for lift-off in a Martian atmosphere 100 times thinner than Earth’s. A built-in heater would protect the helicopter from frigid overnight temperatures that could plunge below minus-130 degrees Fahrenheit.

Elbasyouni helped design Ingenuity’s propulsion system and flight software. “I don’t want to say it’s the most important part, but I think it is,” he said with a chuckle. “You can’t drive a car without an engine.”

That morning, his years of work faced a moment of truth tens of millions of miles away. Any unforeseen error could foil the mission’s success.

A crew at NASA’s mission control room erupted in applause as footage showed the helicopter lifting into the Martian atmosphere. Elbasyouni remembers thinking: “Oh, my God, this thing really flew!”

Now, that triumphant moment seems far removed amid a war that lays bare Earth’s brutal realities — and betrays the wisdom gifted by space exploration.

“When we look at Earth from space, we don’t see borders, languages or religion,” Elbasyouni said. “And here we are profaning the holiness of human life, committing atrocities against ourselves.”

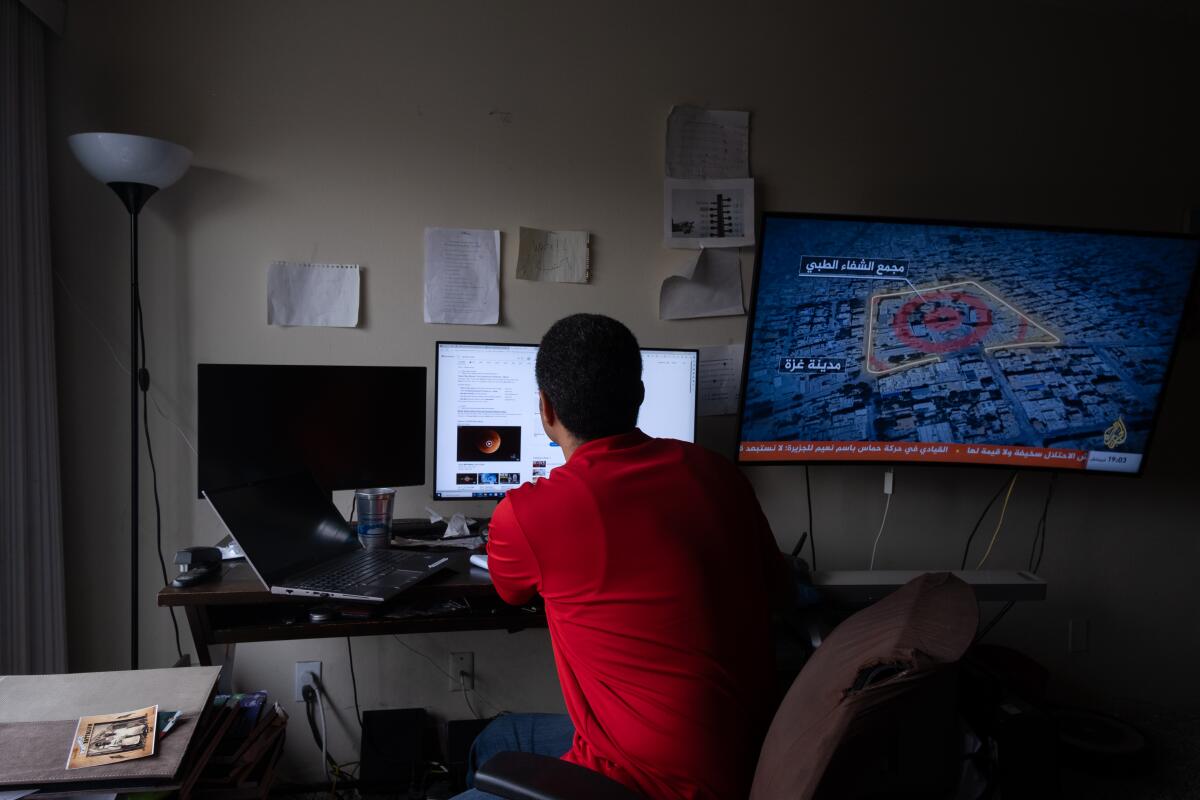

On a recent afternoon, Elbasyouni was somber as he tuned in to Al Jazeera Arabic’s coverage of the Israeli raid on Shifa Hospital. The hallways of Gaza’s largest hospital seemed all too familiar, as Elbasyouni’s father served as director of surgical departments there for several years. The hospital, which Israeli soldiers are scouring on suspicion it housed a Hamas base, is now barely functional, as food, medicine and anesthetics have all but run out.

Elbasyouni last heard from his parents on Nov. 13 when his brother reached them by phone and connected the family. His parents said they were surviving on tap water and canned food but supplies at the clinic were running low. “They hadn’t eaten any vegetables in 10 days,” he said.

Rescuers in Gaza don’t have the equipment, manpower or fuel to search properly for the living, let alone the dead buried among mounds of rubble.

Two days later, Elbasyouni finally received a response to his evacuation request from the Representative Office of Germany in the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah.

An official said in an email that his parents had been added to a list of German citizens eligible for evacuation but that Israeli and Egyptian authorities would have the final say in approving any exit permits through the Rafah border crossing. Fuel shortages from the Israeli siege have led to a telecommunications blackout, but the official promised to find a way to alert Elbasyouni’s parents of any developments.

In the meantime, Elbasyouni has added his voice to calls for a cease-fire. He struggles to remain stoic behind his gentle smile.

With Ingenuity, he triumphed over Mars, an inhospitable planet 293 million miles away. And yet somehow, back in Gaza, the 20-mile distance that would deliver his parents from the ravages of war to the promise of refuge seems far more remote.

“I sent a helicopter to Mars,” he said. “But now I can’t even send food or water to my parents in Gaza.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.