L.A. County supervisors ‘disheartened,’ ‘disturbed’ by restraint rates at L.A. General

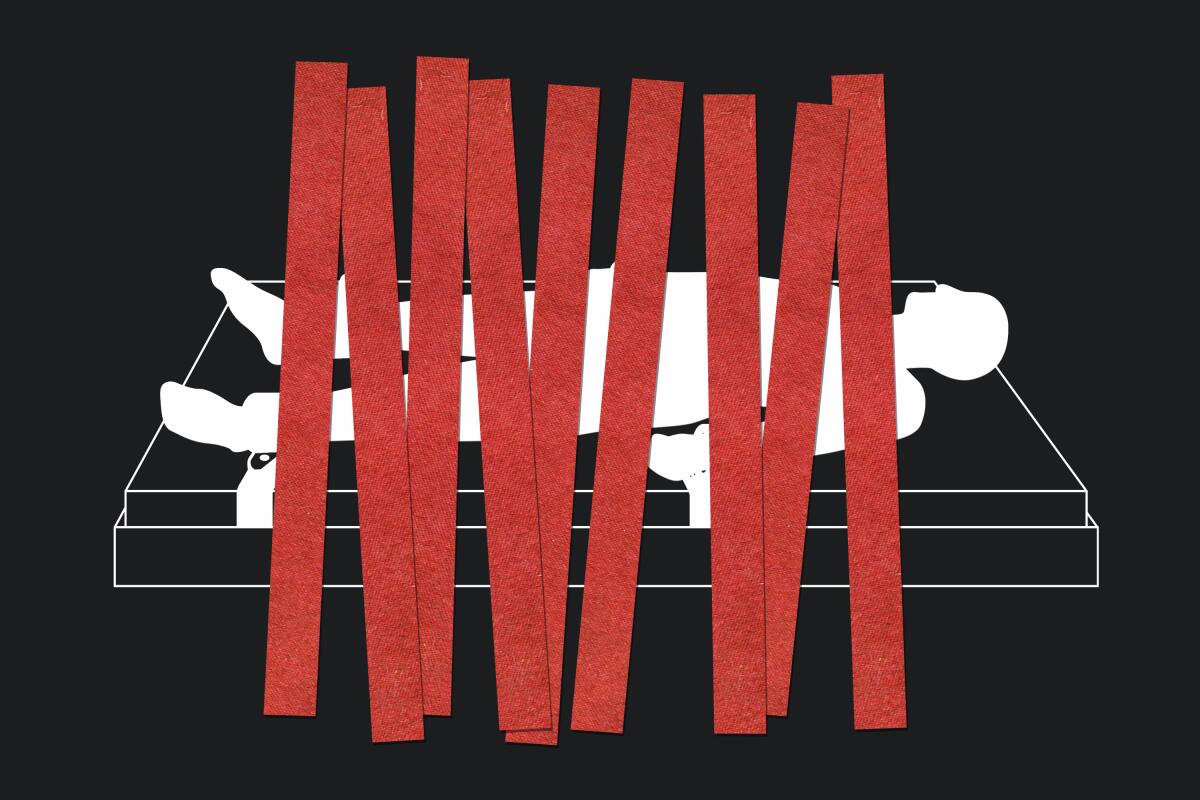

Two Los Angeles County supervisors are calling on health officials to find alternatives to physically restraining patients, voicing concerns after a Times investigation found an L.A. County-run hospital has been restraining psychiatric inpatients at higher rates than any other California facility.

The findings also troubled state and federal lawmakers as well as mental health advocates and experts, some of whom called on the county to take action to reduce the high restraint rate, such as developing a more robust plan to deal with the problem or bringing in an outside consultant to review hospital practices.

The Times’ investigation found that the psychiatric inpatient unit for L.A. General reported a restraint rate more than 50 times higher than the national average for such facilities between 2018 and 2021, ranking it among the highest in the country.

County Supervisor Hilda Solis said that L.A. General, a safety net hospital that serves some of the most vulnerable patients in the county, handles “those with the most complex needs often directly from Men’s Central Jail and Skid Row.” Its main campus in Boyle Heights is located in her supervisorial district.

“Although I recognize that the hospital serves many patients that no other health center will see, I am disheartened to learn of the high use of restraints on patients, and am working to identify ways to drive those rates down,” Solis said in a statement.

A Times investigation digs into what is driving the high use of restraints at L.A. General Medical Center.

That includes working to move the inpatient psychiatric unit, located at the Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center in Willowbrook, onto the main campus, Solis said.

L.A. County officials said psychiatric inpatients at Hawkins are always restrained when transported between the two sites for safety reasons, a practice criticized by some experts. County officials estimated that in 2020, patients spent more than 1,400 hours in restraints while being transported from one campus to the other.

In addition, Solis said she was directing the Department of Health Services — the county agency that runs the hospital — “to identify alternative methods to manage those with more complex behavioral health needs outside the use of restraints.”

County Supervisor Holly Mitchell, who represents the Willowbrook area where Hawkins is located, said she was “deeply disturbed” by the high rates of restraint and wants a public discussion about the issue at a Board of Supervisors meeting.

“I want to understand what staff need in order to treat patients differently — if it’s resources, if it’s training” or more beds countywide for the severely mentally ill, Mitchell said.

Like Solis, Mitchell said she wants county officials to find alternatives to restraint. “We need to talk about how we got here, dissect our causes, and come up with some solutions that are real versus reactionary,” she said.

Mitchell added that as county officials work to relocate the psychiatric inpatient unit from Hawkins to the main L.A. General campus, the setting needs to be “more conducive to health, healing and recovery” for people in the throes of a mental health crisis than the older facility at Hawkins. That could include features like ambient lighting and noise dampening so “you’re not overwhelmed by sounds coming from other rooms.”

California Assemblymember Miguel Santiago (D-Los Angeles), whose district includes L.A. General’s main campus, called the findings “deeply concerning” and said he expects the hospital to address the issue.

“While I recognize that L.A. General treats a significant number of patients with high levels of acuity, excessive use of restraints greatly hinders patient trust and can be deeply traumatizing,” Santiago said in a written statement.

Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Los Angeles) said he and his colleagues were looking into the “concerning” reports and any action that should be taken to ensure “safe and dignified care.”

“Health facilities should be a place where people feel respected and cared for, and I am troubled that this doesn’t appear to be the case for many patients at L.A. General,” the congressman said in a statement.

High rates of restraining psychiatric inpatients do not automatically spur action by regulators, The Times found.

Hospitals are prohibited from restraining psychiatric patients except to prevent them from harming themselves or others, and the practice is discouraged by psychiatric professionals.

L.A. General officials said restraints have been a “last resort intervention” at Hawkins in the face of violent and combative behavior and that its rates had been driven up by a small number of unusually violent patients.

The problem has been exacerbated, hospital officials said, by lengthy waits for longer term care that fuel frustration among patients, resulting in “violent outbursts that require restraint to protect fellow patients and staff alike.” The county has estimated it is short thousands of beds needed for longer term care.

The Department of Health Services said in a recent statement that the Hawkins facility “consistently meets and exceeds regulatory oversight requirements and inspections by individuals with expertise in the management of psychiatric patients, including thorough review of its use of restraints.”

In a statement after the investigation was published, L.A. General officials said its staff was dedicated and compassionate and that The Times investigation “was focused on the wrong issues, and would have better served our community by focusing on violence toward staff,” the shortage of mental health beds and “the very real homelessness and substance abuse crisis” in California.

“Vilifying one of the only hospitals that doesn’t turn away these extremely violent patients is plainly irresponsible and simply unsupported by the facts,” L.A. General said. As evidence of support for the hospital, it also cited Instagram comments that defended the hospital or criticized The Times.

Supervisor Kathryn Barger said the restraint rates reflect the fact that “the population that is presenting itself in our hospitals is far more complex than in years past,” and that L.A. General has been treating patients with a history of violence that other inpatient psychiatric facilities will not admit.

“The issue of high restraints is really, to me, a symptom and not the root cause,” Barger said. More beds for mental health treatment are needed “so that we can get people the help they need before they end up decompensating to the point where they have to be restrained.”

Still, Dr. Roderick Shaner, former medical director of the L.A. County Department of Mental Health, said the hospital needs to develop a detailed plan to bring down restraint rates. Shaner, who worked to reduce the use of restraints in psychiatric facilities before his retirement five years ago, said the county’s one-page plan to reduce restraints at L.A. General has “no teeth” and lacks measurable objectives.

He said it would be good for the county to seek out an outside, independent review of the hospital’s restraint practices, though he cautioned that privacy rules for patients meant that such a review would “have to be done very, very carefully.”

Traute Winters, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness for greater Los Angeles County, echoed Shaner’s suggestion, saying that the high restraint rates “might warrant outsiders coming in and really helping to see what needs to happen and change to improve the situation.”

Winters found it disturbing that The Times analysis showed restraint rates were much higher at L.A. General than at other large safety net hospitals. L.A. General serves “the most difficult of the clients,” she said, “but is it different from a hospital in Manhattan or in San Francisco?”

Mark Gale, criminal justice chair for the group, was concerned about how long some L.A. General patients had been restrained. Records filled out by hospital staff showed nearly 40 patients were restrained for the equivalent of one week or more in a single month since 2018, including a woman who spent an entire month in restraints.

Physically restraining patients can be necessary in some instances, but “there’s no excuse for restraining somebody for a month,” Gale said. “There’s got to be a better way.”

Liz Logsdon, managing attorney with Disability Rights California, said she is sympathetic to front-line staff who feel that their physical safety is in jeopardy and that “this is the only way to manage the situation,” but said there are alternative methods that should be explored.

Based on their statements to The Times, hospital leaders seem to have “decided that this is the only way to manage these behaviors,” Logsdon said. “And I just don’t think that is factually true.”

The Times’ investigation also found that high rates of restraint do not automatically trigger action from federal or California hospital oversight agencies. And the required reporting by hospitals does not give a full picture of restraint use: The federal restraint data measure only what happens to patients who have been admitted to inpatient psychiatric units, such as Hawkins. When psychiatric patients admitted to other units in the hospital are restrained, those incidents are not included in the federal data.

The California Department of Public Health, which regulates acute care hospitals and acute psychiatric hospitals, does not track restraint use on psychiatric patients at the hospitals it licenses. Nor does it monitor federal data on restraint to initiate hospital investigations, an agency spokesperson said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.