THERMAL — This time of year, Hilaria Santiago typically picks bell peppers in the California desert.

But after a pair of unusual back-to-back summer storms washed vegetable seedlings out of fields in the eastern Coachella Valley, Santiago had to find another seasonal job. She’s now sorting dates in a small packinghouse, working just 20 hours a week, with at least 21% of the date crop damaged.

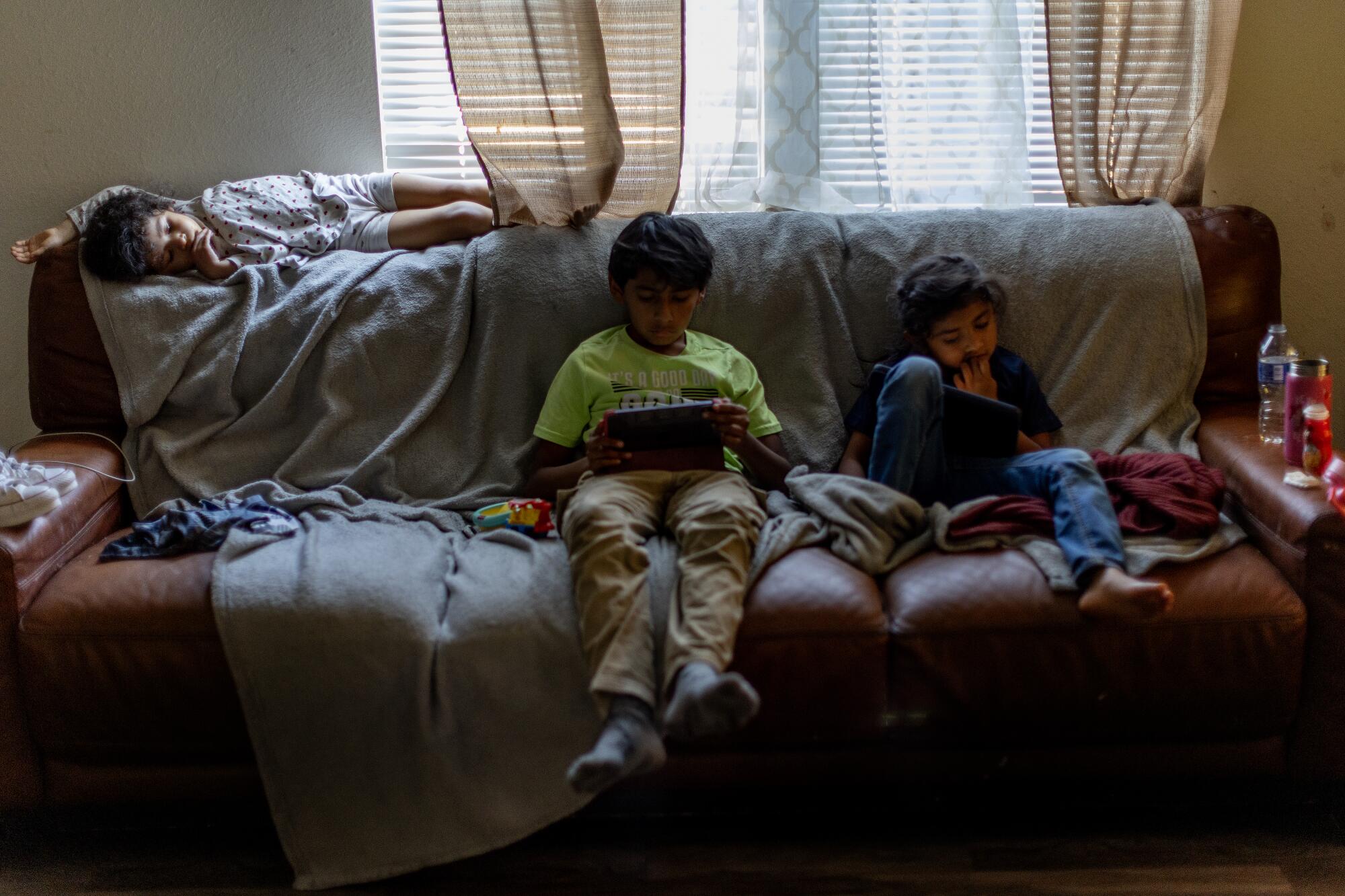

Santiago had already been struggling to support her nine children, ages 3 to 24, even with help from her oldest son, who works in the fields by day and a restaurant by night.

“There are times when the kids want a pizza, or hamburgers, or Chinese food, and if I don’t work, I don’t have enough money to buy these things,” said Santiago, an immigrant from Acapulco.

It’s been more than two months since Hilary — the first tropical storm to hit California in more than 20 years — soaked the region in mid-August. Another storm rolled through less than two weeks later, inundating parts of the desert.

Coachella Valley growers have reported crop losses of an estimated $20 million, with about $18 million stemming from dates, which need hot, dry conditions to thrive, according to the county Agricultural Commissioner’s Office. The storms compounded challenges already facing the industry, growers said, including inflation, increased employee costs and competition from other countries.

“It’s a hit to the industry,” said Albert Keck, president of Hadley Date Gardens and chairman of the California Date Commission. “It’s a hit to the local economy.”

Even before the storm, workers like Santiago were struggling to afford rent, food and gasoline in this majority-Latino region about 30 miles east of Palm Springs. In the unincorporated community of Thermal, nearly 40% of residents live below the poverty line.

The work hasn’t completely dried up — some of it involves cleaning up storm damage. Crews have been repairing vegetable fields, replacing irrigation pipes and weeding newly planted row crops, according to area growers. Those harvesting dates in the fields are busy separating the good fruit from the damaged ones. And workers are planting winter vegetables in undamaged fields, sometimes late into the night, when temperatures are cooler.

But with planting and harvesting schedules disrupted, and date packinghouses sending less volume to market, some laborers say they are working fewer hours or struggling to find work altogether.

“If fields are getting washed away and if product is getting destroyed, then there’s going to be less work to be done,” said date farmer Mark Tadros, the second-generation owner of Aziz Farms in Thermal. “There’s no ifs, ands or buts about it.”

Poor farming communities in Coachella Valley flatlands face dire threat of flooding as Tropical storm Hilary pounds SoCal.

On a recent morning, a small crew of workers sorted dates on Tadros’ farm. Standing below towering palms, they separated fruit that had puffed up and cracked after absorbing too much water, as well as dates that were discolored and possibly filled with black mold.

Nearby, a couple of cows lolled about. The cows play an important role on the farm, eating grass, fertilizing the land and ensuring the bad dates don’t go to waste.

The workers dumped the discarded dates into a huge bin that holds hundreds of pounds of fruit. Tadros estimated they fill the bins every three days.

“Multiply that by picking five days a week for four weeks,” he said. “Not a fun proposition for everybody but these cows.”

Tadros estimated the ranch lost 40% of its Barhi dates, a variety that is yellow and crunchy like an apple. They are currently harvesting Medjool dates, and Tadros expects they’ll lose 30% of that crop, too. They haven’t started on Deglet Noors yet, but, he said, “I am not optimistic.”

“Essentially, you get one shot at harvest every single year,” Tadros said. “This is one of those years where really, the goal is to hope to break even.”

At Aziz Farms, Tadros has six workers harvesting dates in the fields. But with economic pressures and fewer dates making it to market due to the storms, he has scaled down his packinghouse crew from 12 people to seven.

As climate change pushes temperatures to increasing extremes, farmworkers in the Coachella Valley are being exposed to dangerous heat at work and at home.

Maria Arredondo typically prunes and harvests the region’s grape crop, making about $500 a week. But that work doesn’t pick up until December, she said, so this fall she inquired at a date packinghouse near her mobile home park. She was told the crew was full, and her only option was to return repeatedly to see if a spot had opened up.

“The situation is really difficult,” said Arredondo, an immigrant from the Mexican state of Michoacan. “With the way things are, people are not going to leave their jobs so that another person can enter.”

She crams into a trailer with her 11-year-old daughter and her adult son, as well as her adult daughter, son-in-law and two grandchildren. They pay about $520 a month to rent their space in the trailer park, not including utilities.

“I worry — most often at night — because I’m thinking to myself, ‘Tomorrow is another day, I have to pay this bill, and how am I going to do it?’” she said.

Santiago, the mother of nine, pays $810 a month for two trailers in a mobile home park — one for her and her daughters, and one for her sons. She said she worries when she sees workers just beginning to plant crops in bare fields. It’s a reminder that there might not be enough work to go around.

In these moments, she said, she relies on her faith.

“If I were another person, I might be depressed, because this is truly so sad, to see how things are,” she said.

Two months after the storms, some vegetable companies are busy repairing their fields, which provide some jobs for those with the skills to do the work.

Instead of irrigating, fertilizing and growing the carrot crop to maturity, Grimmway Farms is focused on getting its Coachella Valley fields back in shape, said ranch unit director Alex Sanchez. Harvesting is delayed as workers clean debris, level the fields with tractors and once again install irrigation systems. In the meantime, the company has shuffled some of its planting to other areas of the desert southwest.

Grimmway lost about 290 acres of recently planted carrots. Rushing water carved deep canyons in hundreds of acres and sent irrigation pipes sailing a mile away.

“What we did a month and a half before the storms came, now we’ve got to redo that all over again,” Sanchez said. “So in our case, we actually have more work to do in order to get the house back, clean it up and get it back in order.”

Hilda Romero is eager to return to work growing and harvesting vegetables.

Earlier in the summer, she earned about $500 a week harvesting grapes. It was enough for her to split a monthly $1,200 bill — which covers a parking space in a rural mobile home park, as well as electricity, water and trash — with three roommates.

The grape harvest ended in early August, and Romero had saved enough money to pay her portion of the September rent. But then the storms hit, turning the dirt road outside her trailer into a muddy lagoon and sinking her hopes of weeding peppers and other crops beginning in September. A roommate had to cover Romero’s share for October.

“A disaster like this one that has harmed us so badly, I’ve never experienced anything like it,” said Romero, an immigrant from the Mexican state of Sinaloa. She was inside the Coachella office of TODEC, an immigrant advocacy organization that has been distributing one-time financial assistance to unemployed farmworkers. She received a check for $500, which she said she used to pay back her roommate.

Luz Gallegos, executive director of TODEC, said the storms are further proof that seasonal farmworkers are disproportionately affected by natural disasters. She called on the state to extend unemployment benefits to them.

“If they’re not working, they’re not eating, because they rely on their job,” she said.”Their job is their safety net.”

Two days later, Romero’s spirits were improving. She sat outside her trailer, swatting at the swarms of mosquitoes that had descended on the mobile home park since the storms. She had recently spoken with a labor contractor who said a crew of workers might start weeding the next week or the week after.

“It feels as if there is more hope that soon, soon we will begin to work,” she said. “It won’t be too much longer now.”

This article is part of The Times’ equity reporting initiative, focusing on the challenges facing low-income workers and efforts being made to address the economic divide in California. More information about the initiative and its funder, the James Irvine Foundation, can be found here.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.