David Mays, 69, has been living in his Chevy Malibu for nearly two years, and he can’t help but dream about the day when he gets off the waiting list for housing.

“When I’m moved in, that’s going to be a wonderful day, because everything opens up at that point,” Mays told me from the front seat of his vehicle. He parks every night at a downtown Los Angeles garage operated by Safe Parking L.A.

“That’s when my health automatically improves, the swelling in my legs goes down, and I can go ahead and post for my positions,” the unemployed in-home caregiver continued. “That’s going to be a momentous day.”

In California, older adults have been among the fastest-growing segments of the homeless population. In Los Angeles County, the latest count showed an 11% increase in homeless people 65 and older. And roughly 14,000 people of all ages are living in cars, vans and RVs.

Safe Parking L.A., founded in 2017 to give people a safe and legal place to park overnight, operates seven lots. The program — one of several overnight parking operations in the region— has roughly 200 clients. In the latest census, about 44% were 55 and older, while 21% were 62 and older.

The evening I met Mays, he was parked near a 72-year-old unemployed chef. Nearby, a set of grandparents bedded down in a van they’ve been living in for two years. Not far from them, a 64-year-old healthcare worker told me she lost her husband to COVID, and then lost her house to foreclosure.

“I never thought I would be on this side of the fence,” she said, wiping away tears.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

She was parked near Eduardo, 73, and his longtime partner Reina, 69, who live in their Chevy Cruze. He works as a messenger and she as a seamstress, but the pandemic limited her hours and then her factory closed. Eduardo told me they couldn’t handle the rent on a $650 backyard unit in Lynwood, so they moved into their Honda Accord, which conked out six months ago. Then they bought the used Chevy, which broke down two months later and cost them $2,000 in repairs.

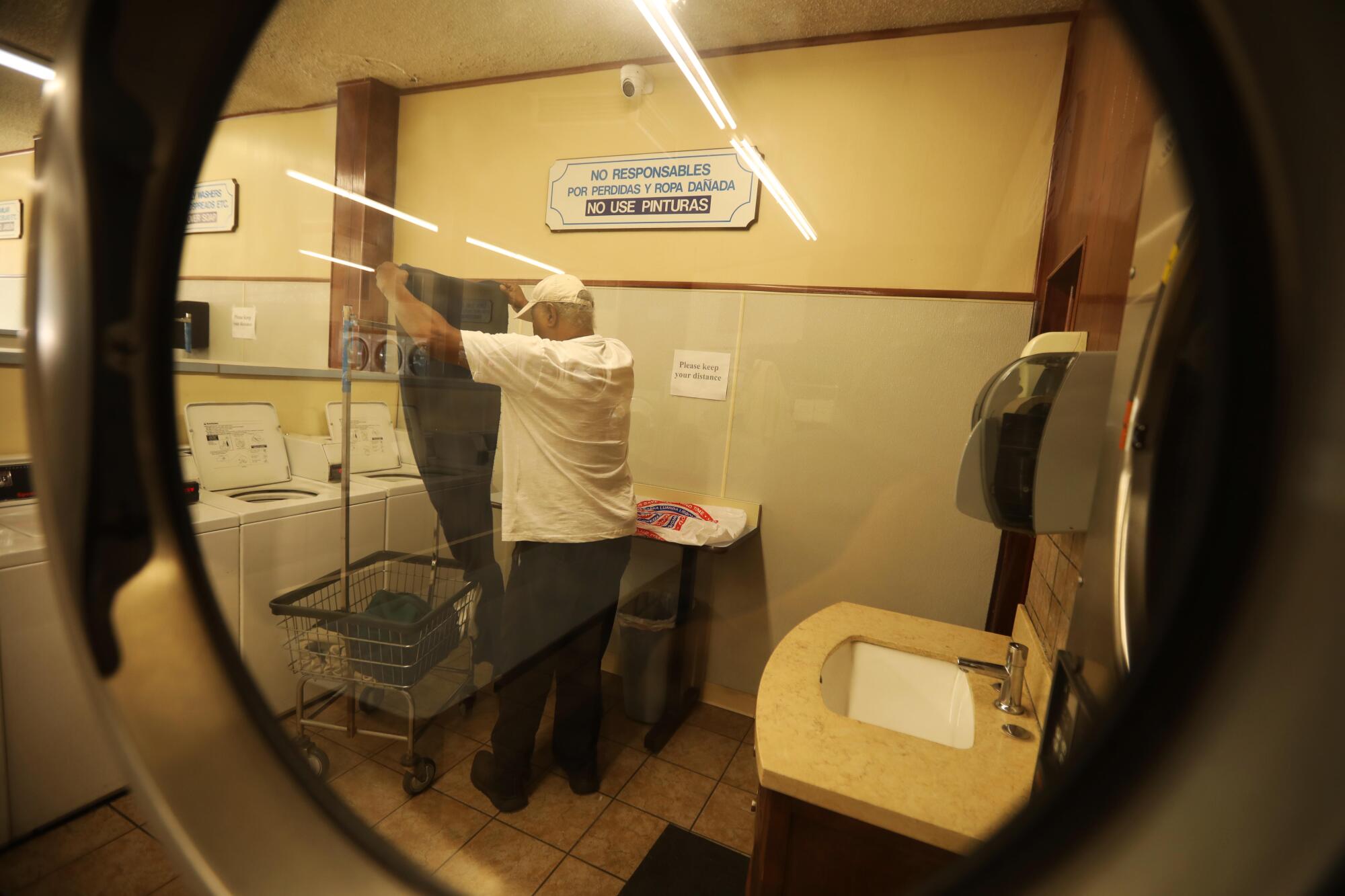

The downtown site is one of the better lots in the Safe Parking program. It’s in a covered garage, with security on site, and a bathroom rather than a porta-potty. Drivers are allowed in at 7:30 p.m. and have to leave 12 hours later. It’s better than taking your chances on the street somewhere, but still an uncomfortable if not depressing way to live.

“We don’t want to get into the car,” Eduardo said, telling me he and Reina seldom get a solid night’s sleep in the front seat of their compact vehicle. “It’s terrible.”

“We’re providing a valuable service,” said Emily Uyeda Kantrim, executive director of the parking program, as she surveyed the scene. “But these are not living conditions that we would say are acceptable, and we understand we have to find a way to provide them a pipeline into affordable housing.”

Some of the clients have complicated histories — legal problems, addiction issues, physical and mental health challenges, family estrangement, poverty and trauma. Others are simply victims of the cruel math of survival in L.A. — wages don’t keep pace with the cost of living and housing — and Black and Latino people are hit hardest. The last option before tarps and tents is this caravan of rolling homes, filing into safe harbor for the night.

The program offers more than free parking. Case managers help clients plot a way out of homelessness. They get paperwork in order, map out housing options, offer links to healthcare and assist with vehicle maintenance. But the ultimate goal — permanent housing — is the biggest challenge, given rising rents and the shortage of good options.

One night I checked out the program’s Hollywood lot, where I met Saul, 55, who has lived in a 2004 Toyota Camry for a year or so. He said he felt as though he’d added 10 years of wear and tear on his body and mind in the last 12 months.

“It just ages you — the stress, you know, and the uncertainty of it all,” said Saul, who told me he had lived with his mother but lost the house in a dispute with siblings after her death.

Saul asked me not to use his last name, which isn’t uncommon. Some people told me they were too prideful; didn’t want friends, family or prospective employers to know they were homeless; or wanted to maintain a modicum of privacy. Saul said he parked on the street briefly before getting into the Safe Parking program.

“It’s not the answer, but it’s a buffer. It’s a sanctuary, almost. A way to gather your wits and maybe your resources,” he said. “In my estimation, two or three days on the street, and you’re done. …You’re going to be transformed into something you don’t want to be.”

Saul’s last job was as a delivery driver, but he’s had trouble finding work lately. He said he’s just a few credits short of a college degree, and he keeps his textbooks in the car for review. Math and economics are his interests. He complained of swelling and stiffness from sleeping scrunched up in his car, unable to flatten out — the same problem David Mays described.

“You don’t know where it ends,” Saul told me. “You don’t know where your health is going, but you know it’s going to get more and more complicated.”

Saul opened his car door and began his nightly ritual.

“I lay down the chair and put down a blanket there, and I have a couple of seat cushions. ... I position them so my back is straight ... and I cover the windows with plastic trash bags. I double them up and no sound gets in.”

Saul is on a waiting list for housing but wonders if being on the street has left him with a case of PTSD, and, if so, whether that might complicate a transition back to a normal life.

“I think what happens is … you’re on a war footing. You start to identify with it. When you’re homeless, money is relatively free and you don’t have rent or dry cleaning. I wonder, if you go back to an apartment … and sink a lot of money into it … and every year they raise your rent, could you be wiped out again?”

At the downtown L.A. lot, Mays told me he had worked for a number of clients as a live-in caregiver. It was a good deal, he said, because he got free rent and food along with decent pay, even if he never had his own space. But clients died, or moved on to nursing homes.

Out of work for a while, he burned through savings and ended up in his car, parked on city streets and in supermarket lots before he got a Safe Parking slot.

“It was dangerous because lunatics would come up and take something and throw it at my car and dent it, or break the window and just walk away,” Mays said. “You have to deal with the police, you have to deal with supermarket managers and you have to deal with the nuts and thugs. I’ve had people come up and use white supremacist stuff on me.”

Mays has maintained a social life, meeting with his “coffee klatch” friends each morning outside a Vons supermarket in West L.A., including Kit Bradley, 69, who lives with his mixed-breed pooch Lea in a 1993 Ford van near the store. When I visited the group one morning, I noticed that Mays, a shade taller than 6 feet 3, has trouble wrenching himself in and out of his vehicle, and he walks a bit gingerly.

“I have massive swelling in my legs from sleeping sitting up, because I can recline, but my legs — I can’t lay them all the way flat,” he said.

Mays said he doesn’t think he can handle the demands of full-time in-home caregiving any longer. He’d prefer a 9-to-5 job, but if he finds one, that could put him in a bind. His income might be too low for him to afford a place to live, but too high for him to qualify for subsidized housing.

His situation is a snapshot of a massive challenge facing society. The population is aging rapidly, but public policy responses move at a slower pace. Here, in the case of Mays, is a homeless elder-care worker who doesn’t know who will care for him as he gets older and his health declines, or where he’ll live, or how he’ll pay his bills. You can multiply the story a thousand times. A million.

But the other day, Mays forwarded me some good news.

“I just wanted you to know that the housing people called and said that my apartment is ready,” he said.

“I’ll believe it when I see it,” he added, but his momentous moment seemed finally within reach after two years in his car.

Stay tuned for more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.