LAUSD moves to bar charter schools from scores of campuses, citing tensions

When Tropical Storm Hilary drenched the interior of a building rented by a charter school at Eastman Elementary — destroying books and computers — some 75 charter students moved into the auditorium and library of the main campus, straining resources and patience.

“It’s just very unfair that the whole school basically has to accommodate the charter school,” said Los Angeles Board of Education member Rocio Rivas last week about the situation at the East L.A. campus.

The tensions and competing needs of L.A. schools — especially more than 100 serving academically struggling, low-income students — were at the heart of a resolution approved by the school board Tuesday that limits where charters can rent on-campus classroom space from the district.

The action marks one of the most significant changes to local charter school policy since the state first required school systems to offer space to charters more than 20 years ago. On Tuesday, in the run-up to the vote, a senior attorney for the California Charter Schools Assn. threatened litigation to protect access to campuses.

Backers defended the legality of the resolution, noting that it instructs L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho to come back in 45 days with policy language vetted by district lawyers.

Charters enroll about one in five public school students within the L.A. school system.

The resolution and Tuesday’s board discussion took on the question of what exactly is available space and who has a right to it, while also shaping the expected battleground for next year’s school board elections.

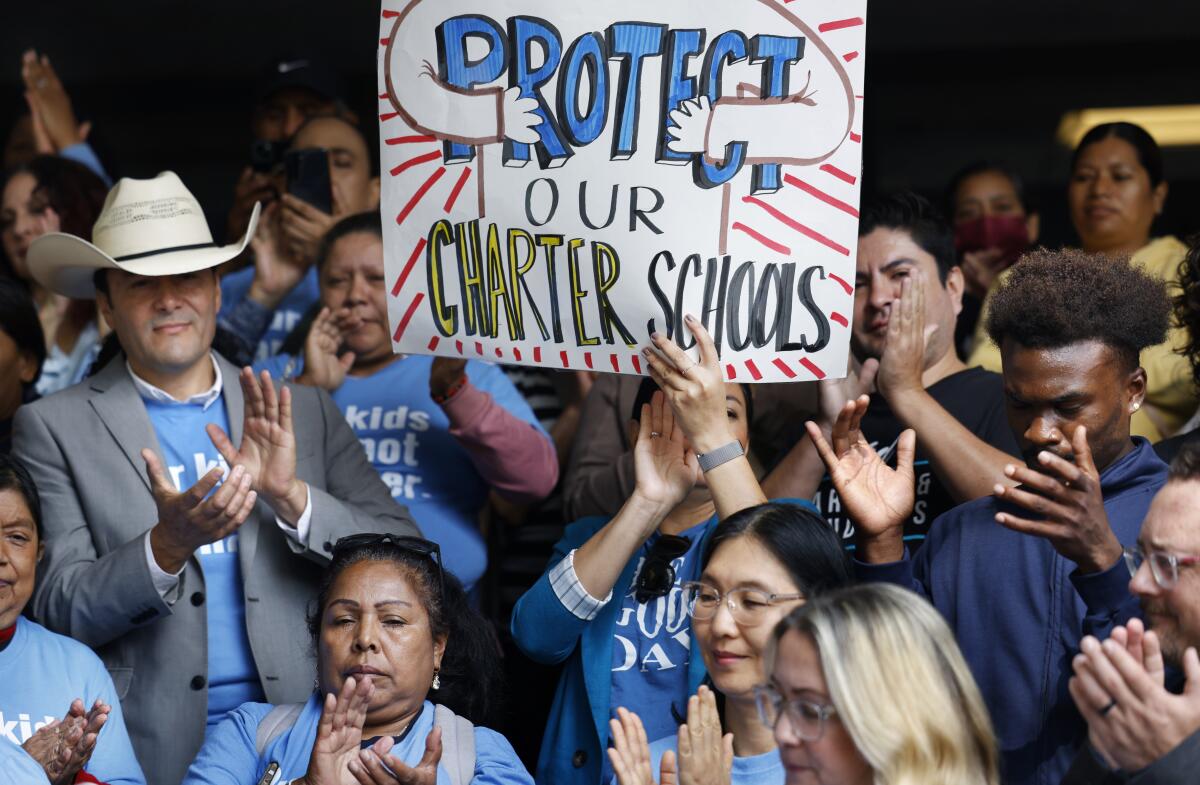

Reflecting the tension over the issue, about 150 charter supporters gathered last week during a school board meeting to press their case.

“All public school students should be treated equally and deserve to learn in a decent classroom — period,” said Myrna Castrejón, president of the California Charter Schools Assn. “That is what the law says.”

Supporters say charters offer families high-quality, diverse schooling options and compel helpful competition.

Charter critics, including some school board members, have long said charters undermine district-run schools by siphoning off more motivated families and funding, and leaving behind students who are more challenging and expensive to educate.

The Los Angeles teachers union has fought to end all campus sharing and offered heavy campaign support for candidates who generally share its views.

Senior LAUSD administrators were among at least 10 who were demoted, reassigned or left the district after a probe of unusually high, poorly documented extra pay.

Within the nation’s second-largest school system, 221 independent charters enroll more than 108,000 students, compared with about 420,000 students in district-run schools. Under state law, all public schools — traditionally managed or charter — have the right to use campuses built, owned and operated by the school district in their area. And the facilities provided for charters must be “reasonably equivalent” to those of nearby district-run schools.

When the state required districts to share classrooms, years of lawsuits ensued in Los Angeles over the meaning of the words “reasonably equivalent.” That debate continued Tuesday, as board members questioned which rooms at a campus had to be ceded to charters.

What has evolved in L.A. is a complex, arduous annual process. Every year, all L.A. Unified principals must inventory available space and justify what would not be available to a charter. Charters in need of space must submit an application by Nov. 1. Charter space requests are typically settled by the end of the following May.

Rivas co-authored the hotly debated resolution with Board President Jackie Goldberg, who cited a litany of harms when campuses have to offer up classrooms that are not used for full-time instruction.

“We are saying to that school that the room your staff was using to work with deaf students to do speech therapy is no longer available,” Goldberg said last week. ”... So go find a corner of your auditorium or, as one of my schools does, find a space on the stairwell in between the first and second floor and have your work with disabled students done ... there.”

Board member Nick Melvoin, who is supportive of charters, said that charters and host schools sometimes get along fine and benefit from working together. He added: “LAUSD in 2023 has enough space for every public school student.”

Goldberg and Rivas each have said they respect the work of charter educators and enrollment choices that parents make. But Rivas in particular has cast charter backers as trying to destroy public education by “privatizing” it. The charter industry, she said, has been “taken over by charter school management organizations, huge industries that are profiting.”

The resolution prohibits charters from moving onto campuses deemed especially vulnerable to harm by disruption.

Community colleges are breaking new ground with more bachelor’s degrees in specialized fields. In the Antelope Valley, a popular program leads to aviation jobs.

These off-limits campuses would include 100 “priority” schools — designated because students have comparatively low academic achievement and also reside in a community with high poverty and other challenges, such as homelessness, high crime rates and poor health.

Also off limits would be campuses that are part of the district’s Black Student Achievement Plan — because Black students at these schools are considered in need of extra support.

“Community schools” — which have special services designed to address the broad needs of children and their families, while also providing families more voice in how a school uses its resources — are also included in the resolution.

About 80% of 50 campuses currently hosting charters fall into these categories, but district staff said about 350 campuses — about one-third of the district — could become exempt from future sharing. That would have a ripple effect of impact on still-eligible campuses.

Before the final vote, Goldberg amended her resolution in an effort to allow all campuses to make more rooms unavailable to charters.

No charter would be forced to move immediately. But if the charter needs more space or makes a “material revision” to its founding or operating documents, it could be barred from all protected campuses. For instance, a charter could have to move out if it decided to add a new grade or increase enrollment. Also, if the host school qualified for more space — and the charter had to move for that reason — its options would be limited by the new rules.

The off-limits campuses share a relevant common characteristic: They set aside more space for extra services, such as providing full-time rooms for speech therapists, tutoring, family counseling or special academic programs such as robotics. Unprotected campuses typically have fewer special services and also might have to squeeze in such services into fewer and smaller spaces.

It is no coincidence that a resolution to limit campus sharing is arriving at this moment, said board member George McKenna, “because this is the first time since I’ve been on this board ... we’ve had a non-charter-school majority.”

The current board majority is less politically beholden to campaign donations from charter supporters, he added.

McKenna and Goldberg — who won office with support from the teachers union — are not running for reelection. That means future charter school policy will be at stake next year in school board elections that are typically the most high-spending in the nation.

Voting for the resolution were Goldberg, Rivas, McKenna and Scott Schmerelson. Voting against it were Melvoin and Tanya Ortiz Franklin. Kelly Gonez abstained.

The unpopularity of campus sharing has, over time, influenced charters to seek their own locations. Eight years ago, 101 charters requested space. This year, there are 52 sharing arrangements on 50 sites.

A new law signed by the governor will bring more scrutiny to school district curriculum decisions. Materials must feature ‘inclusive and diverse perspectives.’

Accommodating the charter left the Eastman library and auditorium suddenly unavailable, meaning that students could not check out books, said teacher Antonia Montes. Students were unable to use the auditorium for a music and dance program.

Extera Public Schools uses two buildings on the 5½-acre Eastman campus. Its focus is to provide hands-on learning to students of East L.A. and Boyle Heights through learning about sustainability and environmental science, including topics related to local resources such as the L.A. River, said Nicole Ann Duquette, Extera’s interim chief executive.

Like other charter operators, she’s concerned about potentially subjective and ambiguous language in the resolution. The resolution calls for ending campus sharing when it would “compromise District schools’ capacity to serve neighborhood children, and/or result in grade-span arrangements that negatively impact student safety and build charter school pipelines.”

Duquette has a different narrative on events at Eastman. She said the charter was displaced because the district had been unable to complete repairs on the rooftop HVAC system before the start of school, essentially leaving the area exposed. She also praised the response from the district and host school once the mishap happened.

“We didn’t want to be in the library or the auditorium either, trust me, but we literally had no classrooms to go into,” Duquette said. This week, the charter resumed use of some rooms while repairs continue in others. The charter also moved into two classroom spaces in the main building that are not used all the time to free up the library and auditorium.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.