Mexican Mafia member who ran Ventura County rackets is killed in Baja California, authorities say

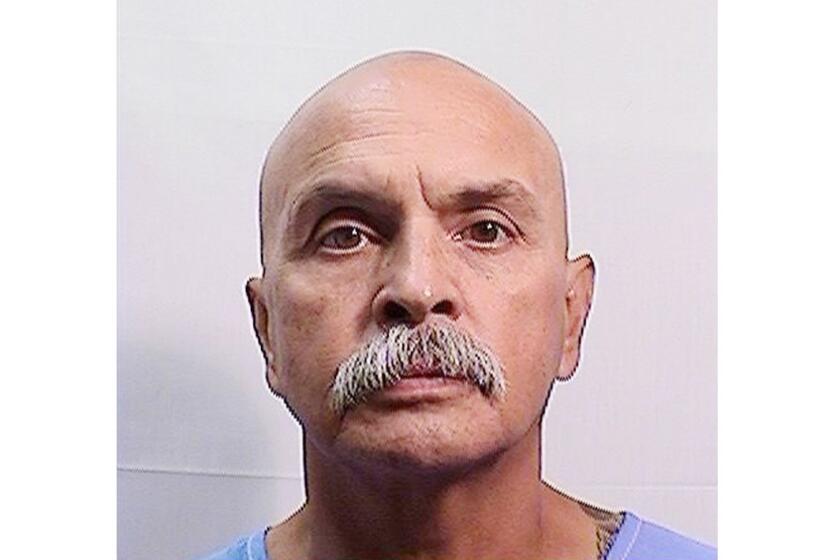

Martin Madrigal Cazares, a fugitive Mexican Mafia member who controlled gangs in Ventura County from a base in Mexico where he developed a drug-trafficking network and brought California-style prison politics to Mexican lockups, was gunned down earlier this month in Baja California, law enforcement sources said.

Details of his death remain scarce. The sources, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak about the ongoing investigation, said they had not yet been informed by Mexican authorities where or when Madrigal, 53, was killed.

Deported in 2006 after serving a six-year federal prison term, Madrigal, nicknamed “Evil,” was known to travel between Tijuana, Rosarito and Ensenada in Baja California, the sources said. Under indictment in the United States on drug trafficking charges and subject to extradition, Madrigal was twice released from Mexican custody under circumstances that are not clear.

Madrigal, the sources said, operated within a shadowy world where established Mexican drug traffickers rub shoulders with uprooted California gang members. Some are fugitives from justice, while others were deported to a country they hardly remember after growing up in the U.S. and serving prison terms.

In Baja California, Mexican Mafia members act as brokers, the sources said, arranging for traffickers to send drugs — mostly methamphetamine — to contacts in California and elsewhere in the United States. Often, one law enforcement official said, the drugs are simply sent via commercial shipping companies.

Six months before his death, Madrigal was arrested in Rosarito. Mexican authorities said he and his nine-man entourage were riding in the bed of a pickup truck carrying military-grade weapons.

Joseph ‘Capone’ Hutchinson’s death may represent fallout from the killing of Michael Torres, a Mexican Mafia member who controlled rackets in the jails.

Raised on the east side of Oxnard, Madrigal came up in the Colonia Chiques gang before being inducted into the Mexican Mafia in the early 2000s, said Leo Duarte, a retired state prisons official who investigated the organization for decades.

After becoming a “made” member of the group, Madrigal “thought he was all that and a bag of chips,” Duarte recalled. His outsized ego rubbed many Mexican Mafia members the wrong way. One was Thomas “Wino” Grajeda, who mailed a letter to Madrigal that began, “Órale Martin, just these few lines your way hoping that they find you well, considering that things have somewhat gone to your head.”

In the letter, obtained by The Times, Grajeda rebuked Madrigal for what he considered to be abuses of his newfound authority. “Keep in mind,” Grajeda signed off, “you make your bed in life or the life we live, then sleep on it. I don’t want to hear no crying later on.”

A Mexican national, Madrigal served a 77-month sentence for illegally reentering the country at federal penitentiaries in Victorville and Leavenworth, Kan., law enforcement records show.

After his deportation in 2006, Madrigal retained control of his old gang and others in Ventura County, according to investigations by the FBI and the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department. Wiretapped calls revealed that Madrigal’s lieutenants were collecting “taxes” from gangs and drug dealers and sending the money to Madrigal, who was being held in a high-security Mexican prison on unknown charges.

One of his underlings in California, Edwin “Sporty” Mora, called Madrigal’s wife, Lina Fuentes, and promised to send Madrigal a letter. “Letting your husband know play for play what I’m doing out here. Pretty much like who do I got managing each city,” Mora said, according to a recording of the call reviewed by The Times.

Mora said a dealer’s weekly dues started at $100. “But if they’re doing like a half-pound, a pound, you want at least $250 to $300 a week from them,” he said.

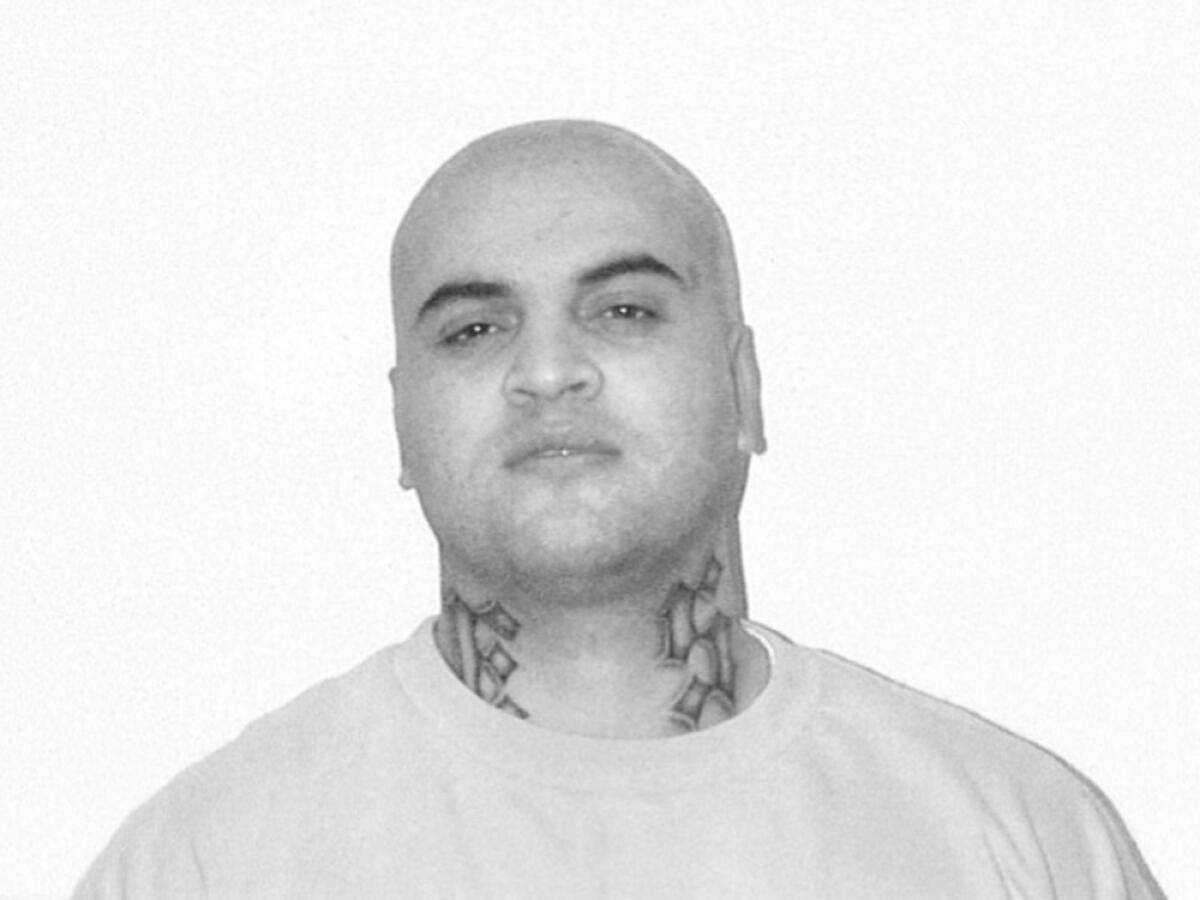

Michael “Mike Boo” Moreno was sentenced to 11 years in prison for conspiring with the cartel La Familia Michoacán to distribute methamphetamine in the United States.

Mora complained that one dealer offered to pay just $500 a month. “I said, ‘Look, dog. Let’s do the math. You’re making anywhere from 35 to $4,000 a month. And you mean to tell me you’re only going to give me $500?’” When the dealer whined about having bills to pay, Mora said he told him, “I know that, dog, but I can shut you down right now to where you ain’t going to have that $4,000 coming in.”

Mora asked Fuentes to get her husband’s blessing to “smash” an Oxnard gang member who was falsely claiming to be working for the Mexican Mafia. “I need to make a statement with this fool,” he said.

Fuentes said she would send the request through a lawyer who was visiting Madrigal in prison. “I already know — you already know ‚ what he’s going to say,” Fuentes told Mora.

Madrigal, Fuentes and Mora were all charged in federal court in 2013 with conspiring to traffic meth in Ventura County. Mora’s federal case was dismissed after county prosecutors convicted him of conspiring to commit extortion and drug trafficking in 2015. Now 39, Mora is serving a 23-year sentence in Calipatria State Prison.

Fuentes remains a fugitive. Prosecutors filed paperwork to extradite Madrigal from Mexico, where they said he was already serving life in prison, but he was never handed over to U.S. authorities — and eventually was sprung from custody.

Madrigal became locked in a bitter power struggle with another Mexican Mafia member, Michael “Mike Boo” Moreno, who was contesting not just Madrigal’s hold over the Ventura area but his collections rackets in prisons in California and Mississippi, wiretapped calls show.

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

Informed that some inmates were still taking direction from Madrigal, Moreno was overheard on the wiretap telling an underling: “Whoever continues, they’re going against what we tell them, man.”

“He had his opportunity already,” Moreno continued. “He had his chances. We gave him the benefit of the doubt. And he still screwed up. And whoever continues to f— with him after we already told them, they’re going to find themselves in trouble too.”

Moreno was arrested in California in 2013 and released this year after pleading guilty to conspiring to distribute methamphetamine.

According to records and sources, at least a half-dozen Mexican Mafia members from California are now operating in Baja California. Madrigal was not the first of them to be killed.

Francisco “Sleeper” Escalante and Ramon “Thumper” Tanory, both members of the 18th Street gang who served 21-year terms in federal prison for distributing cocaine, were doing business with Mexican drug traffickers in Baja California when they came into conflict with Mexican Mafia members from the California prison system who believed the two had not been “properly vetted,” a law enforcement document says. Both men were killed in Mexico in 2019.

The evening of Jan. 24, 2023, officers from Tijuana’s police department and Mexico’s national guard arrested Madrigal and nine other men near the beaches of Rosarito, Mexican media reported.

The men were traveling in a Ford F-150 with California license plates, carrying an arsenal of assault rifles and handguns, authorities said. Police arrested them on a charge of possessing guns that only military personnel are allowed to carry, the publication Punto Norte reported. Baja California authorities published photographs of Madrigal and the other detainees with their faces blurred, standing in front of a table arrayed with the seized weaponry.

A terminally ill Mexican Mafia member expounded on the current state of the gang from his prison cell before he was released to die at home.

Held in a Tijuana jail, Madrigal found that many of the inmates were deported California gang members accustomed to taking orders from the Mexican Mafia, said one law enforcement official who wasn’t authorized to speak to the media and requested anonymity. He began taxing the drug trade and meting out discipline to those who didn’t go along, the source said, and he proved such a headache to administrators that they transferred him from lockup to lockup, hoping to break his hold over the jail rackets.

At some point, Madrigal was released from custody despite being named in two U.S. cases — one federal and another in Ventura County — in which he was subject to extradition. American officials said their Mexican counterparts have never explained why Madrigal was allowed to walk free.

Officials from the Mexican attorney general’s office didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A source familiar with Tijuana’s drug trade, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisal from the Mexican Mafia, said that at the time of his death, Madrigal was doing business with two brothers, Rene and Alfonso Arzate Garcia, whom Treasury Department officials named last month as the Sinaloa cartel’s plaza bosses in Tijuana.

It’s unclear whether Madrigal’s dealings with drug traffickers or some internal dispute within the Mexican Mafia led to his death, U.S. officials said. One source who viewed a photograph of Madrigal’s body said he dressed the part of the California gangster to the end: He wore a Chicago Bears jersey and a Santa Muerte pendant around his neck.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.