La Habra condo owners see a gaping chasm where their greenbelt used to be

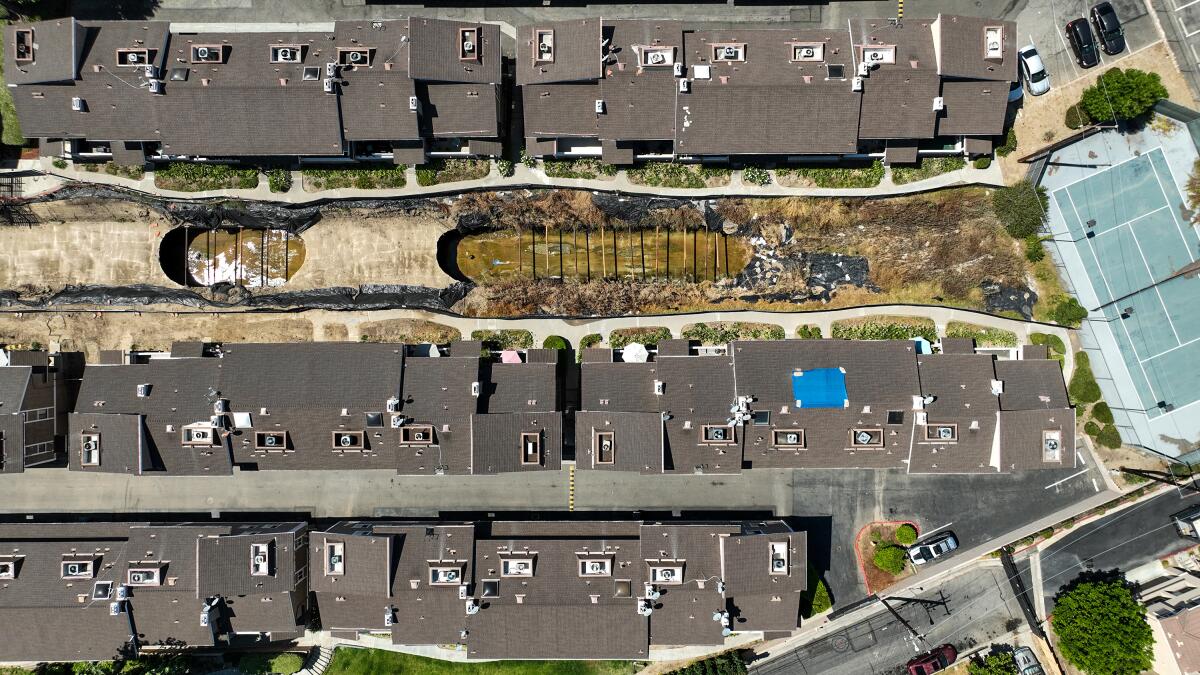

The chasm runs the full length of the condominium complex, from the shuttered tennis court to the shuttered pool. Measuring more than 500 feet long and 20 feet wide, the gash divides the complex in two, its weed-choked perimeter cordoned off with chain-link fencing. A grimy trickle of water oozes along the chasm’s concrete floor a dozen feet below, like some ugly open wound that just won’t heal.

Welcome to Coyote Village, a 70-unit condo complex in suburban La Habra whose residents have been living out a homeowner’s nightmare. Over the last four years, portions of the tree-lined greenbelt that once shaded the complex have violently collapsed into a concrete maw below. That’s because, unbeknownst to most residents, the greenbelt wasn’t built on solid earth. Running beneath it is a cavernous flood channel that decades ago was sealed with a concrete lid then topped with mounds of soil and landscaped with pine trees.

The first collapse of the concealed lid came in January 2019, when a section of the greenbelt near the tennis court caved in, exposing the flood channel below. The second implosion came in March, when heavy winter rains saturated the greenbelt and the concrete lid couldn’t handle the weight of the soggy soil and towering pines. This time, the collapse took out a huge swath of the greenbelt near the community pool.

Most residents were shocked to learn that their complex was built on top of a private canal that plugs into Orange County’s larger Imperial Channel, which routes storm water out of La Habra, Brea and Fullerton. It stood as the only covered private channel in the county’s 380-mile public storm drain system.

And that “private” designation is where the residents’ encountered another chasm, in the form of a years-long legal battle.

After the 2019 collapse, the county did some cleanup work at the site and provided security fencing around the exposed portion of the channel. Following the March 15 collapse, La Habra brought in construction crews to excavate the channel, which at that point was clogged with dirt, tree limbs and concrete that the city worried would create a damming effect in the broader drainage system during future storms.

But the city’s work stopped there.

La Habra officials have argued since the first collapse that the channel belongs to the complex. And worse, that the channel’s concrete lid had been improperly covered with a breadth of landscaping that violated what had been approved in the city permitting process. According to the city, the homeowners association that represents Coyote Village is responsible for repairing and rebuilding the channel.

The Coyote Village Homeowners Assn. has challenged that stance in a running legal battle, started in 2020, contending the channel is integral to a larger public system and was damaged by public use without just compensation. It has sued the city, the county and the county flood control district, among others, for relief.

“While the conduit runs through the HOA property, the water is public,” said John Peterson, an attorney representing the homeowners group. “The public needs to share in the responsibilities.”

State Sen. Josh Newman, a Democrat whose district encompasses La Habra, tried to broker a solution last summer and was able to secure $8.5 million in state funding to repair the flood channel. “The residents were wholly unprepared and financially unequipped to deal with this,” Newman said. “I was happy to secure those funds.”

But a year later, that money remains unspent.

La Habra initially questioned the propriety of expenditure, asking the state Atty. General’s Office if the allocation could be considered an improper gift of public funds. The state’s Legislative Counsel determined it was not. In the months since, the city and homeowners association have haggled over who would run the major construction project, with the HOA concerned it does not have the expertise and city officials reluctant to take charge of repairs on a canal they consider private property.

Residents have watched in a mix of frustration and resignation as the saga has unfolded.

Jan Duncan, an HOA board member, said she put her Coyote Village loft on the market in June and received six offers the first week. Then came questions about the flood channel and why it hasn’t been fixed in four years. In short order, every offer was rescinded.

“I cannot give buyers anything in writing to guarantee that this is going to be resolved,” she said. “Without that, they’re uncomfortable. I can’t blame them.”

Justin Marinello is among the parents in the complex who worry about the safety risk the exposed channel poses for children. His condo looks out on the gritty channel and his 4-year-old son had a front-row view of the city’s excavation work after the March collapse.

“My son enjoyed watching the construction because he likes giant Tonka toys playing with dirt,” Marinello said. “But it would be nice to be able to open the door up and just have some grass for him to run on.”

On the other side of the chasm, Lizeth Ruiz knew about the exposed channel when she moved to her condo in 2019 but figured it would be quickly repaired. Instead, she finds herself fending off mosquitoes that breed in the canal’s dingy water. “Now, I keep everything closed and have to be more mindful about wearing pants instead of shorts,” Ruiz said, holding her newborn baby tight.

Landslides in Orange County continue to disrupt the coastal rail line that carries Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner. Is it time to trade stunning views for a reliable route?

As the summer heat soars, the concrete channel is lined with dry weeds that rise taller than the 6-foot safety fencing. The channel itself is defaced with graffiti. Residents continue to pay $390 in monthly homeowners fees even though the channel’s collapse has sidelined amenities like the tennis court and pool.

It marks a wrenching chapter in the life of a property with an eccentric history.

In mid-century La Habra, a ranch owner flooded a portion of the area to create a lake and islet, deemed “Monkey Island,” where he let feral monkeys roam free. He also eyed the land for a track that would host ostrich races. At the time, ostrich farms were a popular tourist attraction in Orange County.

Later, the lake was drained and La Habra city leaders opted to go a development direction they considered more forward-thinking, erecting a shopping plaza and post office on the site.

In 1978, developer Loren Hendrix proposed an adjacent 70-unit condominium complex, when such communities were still novel in Orange County as an affordable alternative to single-family homes. Without yards to maintain, he envisioned residents being able to stroll along a landscaped creek — a dressed-up version of the flood control channel that crossed the property — as a key selling point.

But Hendrix faced stiff questions from city staff about how he planned to protect children from hazards posed by the channel-turned-creek. Archival records show the county flood control district rejected Hendrix’s creek design. The district recommended design changes Hendrix considered too costly. Instead, the complex would host an enclosed flood channel masked with landscaping.

La Habra City Council members approved the development in April 1979 on the condition that Hendrix’s design be approved by the city’s chief building inspector and the county flood control district. A year later, the building inspector wrote that the complex was “substantially in compliance” with applicable codes. It’s not clear in county records whether the flood control district ever approved the design.

In any case, the condo development and greenbelt were built. And for 40 years, storm runoff flowed through the underground channel unbeknownst to most residents until the 2019 collapse.

The investigation details the influence of lobbyists and other unelected power brokers on the city and comes amid an ongoing FBI investigation.

La Habra city officials say the cave-ins are more about what was built on top of the channel than what lies below.

Deputy City Atty. Gary Kranker contends that at the time of the 2019 collapse the soil piled above the channel ran 9 feet deep — 6 feet more than the greenbelt design approved by the city — and that the pine trees that by then stood 80 feet tall contributed to the channel lid’s failure.

“It’s the obligation of the individual constructing the channel, or in this case, the channel roof, to make sure it was done properly,” he said. “Based upon the calculations that we have, it would have been done properly had it only had 3 feet of soil.”

And he faults the homeowners association for failing to take aggressive action to alleviate the risks between the first cave-in and the implosion in March. “To be quite candid, [they] did not do anything to try and alleviate this condition,” he said. “They could have hired someone to remove the soil, one wheelbarrow at a time.”

Last year, the homeowners association sued Hendrix, the complex developer, for fraud. The complaint alleged that he concealed the channel and any maintenance responsibilities from the association so he could sell condos “more quickly and at higher prices.” Peterson, the association’s attorney, said a settlement agreement compels Hendrix to find the insurance policies that covered the development and assign the rights over to the association.

Hendrix did not respond to requests for comment through his attorney.

Last week, representatives for the city and homeowners association said they were closing in on an agreement for moving forward with repairs that would free up the $8.5 million in state funding. Once a resolution is reached, the canal’s reconstruction is expected to take at least a year.

Roma Damo, who has lived at Coyote Village for 35 years, doesn’t see much light at the end of the tunnel — or flood channel, in her case.

“I’m seriously thinking about renting this condo out and getting myself an apartment,” said Damo, 88, eyeing the degraded channel outside her condo windows. “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life here looking at this.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.