Compensation for forced sterilizations in California ends soon. Here’s how to apply

After the state sterilized thousands of Californians without their consent, lawmakers offered reparations in 2021 by creating the Forced or Involuntary Sterilization Compensation Program. But if you’re eligible for compensation, you need to apply soon — the program is due to expire at the end of this year.

Between 1909 and 1979, state-run hospitals and clinics forcibly sterilized an estimated 20,000 mostly Black, Latino and Indigenous people, in keeping with state eugenics policies. Even after California banned the practice in 1979, the state continued to sterilize inmates in California women’s prisons. The procedures performed without the patients’ consent included hysterectomies, ovary removals and tubal ligations.

Jennifer James, an assistant professor at UC San Francisco and an advocate for sterilization survivors, said some of them were asked to sign consent forms that weren’t in their native language or once they were under anesthesia.

“People went in for one procedure and didn’t know until after they came out that they’d had a hysterectomy,” she said. “People thought they were consenting to having fibroids removed; they thought they were consenting to biopsies. They consented to having organs removed if there was cancer found, and those organs are removed without those criteria being met.”

Anyone who underwent one of these medically unnecessary procedures at a state hospital, prison or other facility is eligible for a piece of the $4.5 million that the state has reserved for survivors. But the deadline for applying is Dec. 31, 2023.

It’s time for California to make amends for one of the most horrific and shameful episodes in the state’s history.

According to James, only 100 people have been approved for compensation thus far, including only three of the 20,000 who were sterilized between 1909 and 1979. Although many of that group are no longer alive, James said, researchers at the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab believe there are hundreds still living who would be eligible.

Many survivors don’t know about the program, and some of those who do have been struggling to navigate the process. Some don’t have any records or access to records of what happened to them.

In addition, hundreds of people have applied and been denied. Many people had procedures such as endometrial ablation that drastically limited their ability to get pregnant, yet aren’t considered sterilizing procedures so are not eligible for compensation — a characterization that James and other advocates have criticized.

Along those lines, some people have a hard time proving whether they were fertile after their procedures.

“Especially if you’ve been incarcerated since then, or you were incarcerated throughout your childbearing years, there may not be a way to document or prove your ability to have children,” James said.

The Center for Investigative Reporting reported in 2013 that at least 144 people incarcerated in California women’s prisons were sterilized with tubal ligation between 2006 and 2013.

“That came to light because tubal ligations were a procedure that people thought was not supposed to be happening” in prisons, James said.

“The state did an audit and corroborated those findings. They also found that during that time period between fiscal year 2005-06 and fiscal year 2012-13, a total of about 800 people had some form of sterilizing procedure,” she said.

California wants to offer reparations to victims of its forced sterilization programs. The state didn’t ban the practice until 2014.

How to apply for compensation

Go to the California Victims Compensations Board website to apply online. You can also find a copy of the application on the website to print out and mail in. The website includes detailed application instructions.

You do not need documentation of your sterilization to apply. Once you’ve submitted an application, it becomes the state’s responsibility to find the records.

The state encourages applicants to include any information that could help in that search. James says the best thing you can do is describe what happened, and what procedure you thought you were getting versus what was performed. Also, indicate when and where it happened if possible.

If you do have documentation, the compensation board accepts:

- Medical records of your sterilization procedure.

- A record of the recommendation that you be sterilized.

- Surgical consent forms.

- Relevant court or institutional records.

- A signed statement by someone with knowledge of the sterilization. This could be you, your physician, or someone else.

- Any other documentation that supports eligibility.

The California Coalition for Women Prisoners created a Prison Medical Record Request guide to make it easier for survivors to get their documents in order.

All applications are confidential. The victims compensation board says on its website that “information may be shared with other entities, but only to verify eligibility.”

A representative may apply on your behalf if they can show proof that they are legally authorized to represent you.

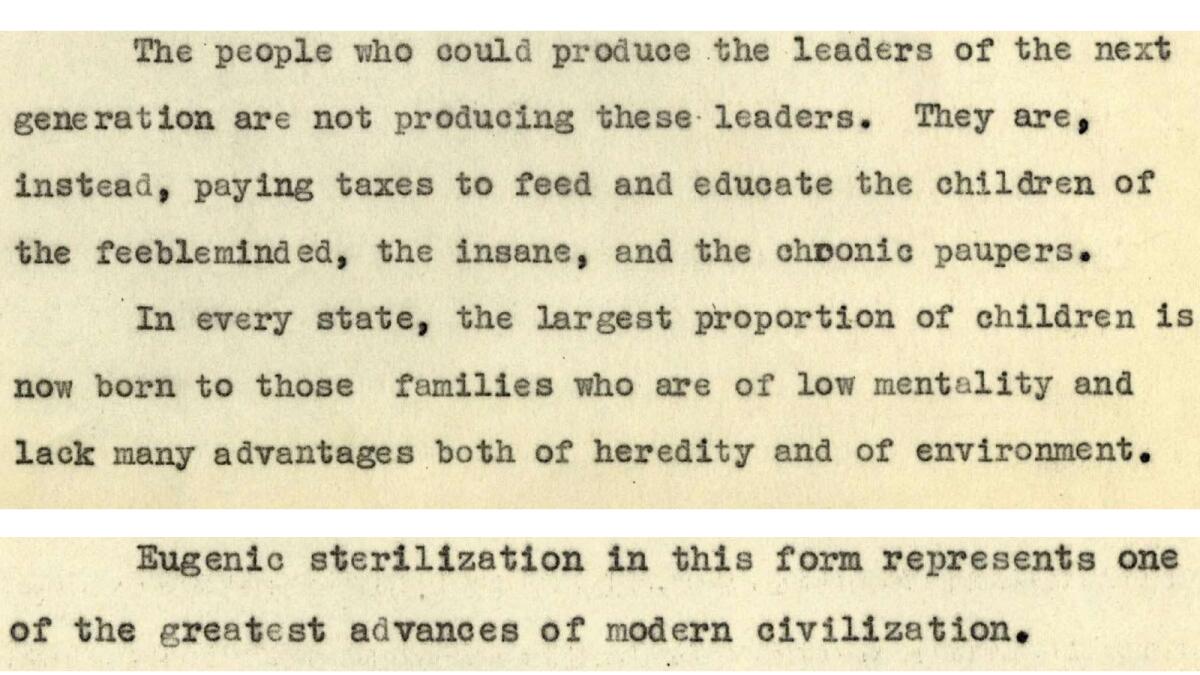

Thousands of people were sterilized by the state during a pernicious eugenics drive that peaked in the 1930s and that even inspired Nazi Germany.

The board says it will make initial payments within 60 days of confirming an applicant’s eligibility. There may eventually be a second payment, depending on how many people apply.

“After all applications are processed and all initial payments are made,” the board says, “any remaining program funds will be disbursed evenly to the qualified recipients by March 31, 2024.”

For further assistance, you can reach the California Victim Compensation Board at 1-800-777-9229 between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. Monday through Friday or by email at [email protected].

Who can help me apply for sterilization compensation?

James recommends that people who are or have been incarcerated reach out to the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, which she says has “a lot of advocates who’ve been supporting people in applying and can connect folks with resources and support in this process.”

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.