TULARE LAKE BASIN, Calif. — In the lowlands of the San Joaquin Valley, last winter’s torrential storms revived an ancient body of water drained and dredged decades ago, its clay lakebed transformed into a powerhouse of industrial agriculture.

Rivers swollen with biblical amounts of rainfall overwhelmed the network of levees and irrigation canals that weave through the basin diverting water for farm and livestock use. Tulare Lake, once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, was reborn, swallowing thousands of acres cultivated for tomatoes and cotton and vast orchards of almond and pistachio trees. In the months since the storms abated, the lake continues to take in runoff from a record snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada, blurring the lines between nature and farmland.

Today, Tulare Lake, roughly the size of Lake Tahoe, appears like a mirage in the desert. Winds glaze off its algae-pocked surface, cooling the summer air, as ducks and egrets wade nearby. Roads that once serviced farms, dairies, chicken barns and cotton gins abruptly give way to lake, their routes discernible only by the tops of telephone poles that cast cross-shaped shadows on the placid waters.

The lake’s rebirth has reshaped life in the Tulare basin and likely will do so for years to come. Some residents grew up picking cotton here. Others found their way to the basin as adults, fell in love with the country sunsets and never left. After a winter of hardships, they remain committed to the San Joaquin Valley and its remarkable seasonal rhythms.

Here are some of their stories.

Jerry Jones, 74, Lemoore

Jerry Jones can point out where nearly every oak tree once stood near the Island District, a triangle of land in Kings County on the north end of Lemoore, bordered by the North and South forks of the Kings River. As a teen, he roamed Lemoore on foot, before the river was so heavily depleted for agriculture, draining the oaks of their sustenance.

Jones was raised in Lemoore, now a farm town of 27,000, with nine siblings. He remembers wanting to be a farmer, like his grandfather, who settled in the area in 1898, and his father. For a time, Jones’ father managed 20 acres of cotton, but competition for water and labor made it a difficult business, and he eventually sold the land.

Jones grew up picking cotton and grapes to earn money for his school clothes. With dark brown skin and green eyes, his mother was adamant that they call themselves colored and identify as Black. It wasn’t until he was older, he said, that he realized his family was Native American, his mother an Apache and his father of Cherokee descent. His mother had lied to protect them, worried that their American Indian heritage would make them targets of suspicion and mistreatment.

With a soft smile, he recounted near-death experiences while growing up in the rugged countryside. The time his shirt got caught in a tractor. The time he dove in too close to the riverbank and got trapped in tree roots. The time he and a friend rode their horses into a canal filled with quicksand. “It was part of the day,” he said with a laugh.

He’s one of the few souls in Kings County who does not shy away from criticizing the J.G. Boswell Co., the basin’s largest landowner, for its dominating influence over water management. Jones is a general contractor with no vast ranch of his own, just a few acres where he grows feed for his animals.

Jones worries what will become of the Tulare basin if the biggest landowners continue to manipulate water flow. He can point out how the landscape has been changed by human hands. That includes once mighty rivers being sapped for irrigation, and in the drought years, relentless groundwater pumping that has caused portions of the valley floor to sink; and in the midst of this year’s epic storms, orchestrating levee building and levee breaks that affected what land got flooded.

“When they want water, they get water. When they don’t want water, guess what? They try to run it out someplace else,” he said. Tulare Lake’s resurgence is great, he said, but the troubles that come with it — flooded farmland, lost profits — are man-made.

“They created it, this catastrophe,” he said. “They’re just messing with Mother Nature.”

Marilyn Nolan, 79, Corcoran

You can find Marilyn Nolan most days among piles of clothes and toys and food boxes in a warehouse behind Corcoran’s Emergency Aid Thrift Shop. She has run the shop for 40 years, her hands ever in motion, sorting through donated clothes and shoes and household wares, carefully wrapping each item in a plastic bag.

The items go into one of two piles: for free or for sale. After years of doing this work, Nolan said she has a knack for what should be free and what can be used to raise money for the store. She sells dresses for $5.95 and gifts baby blankets to new mothers. She has watched newborns grow up, first coming in with their moms, then visiting the shop as teens, and eventually leaving Corcoran for bigger cities with more jobs.

Born in Los Banos to parents who migrated west from Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl, Nolan has only ever really known life in the San Joaquin Valley. She learned how to pick cotton in Tulare, attended Corcoran High, and stayed in town to work at a Caterpillar dealership. She got roped into volunteering for an organization that donated clothing and food to children, and that evolved into the thrift shop.

As executive director of the shop, Nolan has declined to take a salary. She uses the store’s proceeds to operate a companion food pantry for the county’s neediest.

Her store has been a well of support for Corcoran, many of whose residents work as farmhands or staff the maximum-security state prison in town. The thrift shop has been a staple for clothing, sundries and food boxes, first as the punishing winter storms put people out of work, and now as exhausted crews work to fortify the earthen levees that stand between Corcoran and the lapping waters of the newly formed Tulare Lake.

“We’ve had men who had their hours cut quite a bit, and so that’s why we’re giving out food during the week now. We had about 50 families in this morning,” she said on a recent weekday, as she plucked a pair of denim jeans from a shopping cart and added them, neatly folded, to a pile.

Nolan, diagnosed with mouth cancer, said she intends to retire at year’s end. But there’s a lot to do before then. The walls need repainting and the back of the shop could use renovation.

She’ll keep at it as long as she is able, she said, because that’s just the nature of people in Corcoran, a place she calls the “can-do city.”

“I do as I’m told, honest,” she said, “and I’m told from above.”

Javier De La Cruz, 40, Corcoran

Although Corcoran has escaped catastrophic flooding, Javier De La Cruz wants it known that families like his lost nearly everything with Tulare Lake’s rise.

De La Cruz works for Foster Farms, which runs a massive chicken processing plant in Corcoran. As an assistant manager, he helped tend to more than a million chickens housed at the ranch. He rented a three-bedroom house on the property, where he lived with his partner and their seven children. They had a basketball hoop in the driveway and a backyard where the children could run, and a few neighboring families who also worked on the ranch.

But they lost everything on March 18, when the water coursed in fast. With just more than an hour’s notice, they managed to grab a few bags of clothing and documents before leaving. “We have to start over from the bottom,” De La Cruz said.

As of late June, the ranch remained underwater, along with the cavernous barns where he said chickens drowned in their coops. The family of nine bounced around, moving in temporarily with family before he landed another job with Foster Farms in Fresno County. He’s holding out hope that maybe soon, as the waters recede, he’ll get a chance to stop by his old home to see if there is anything left to recover.

Despite the setback, De La Cruz said he’ll do all he can to keep his family in the valley. He moved there at 21, he said, from his hometown of Lynwood, to escape a “bad life” of violence and gangs in southeast Los Angeles County.

“Over there, there’s more traffic, life is faster, rent is higher,” De La Cruz said. “It’s more peaceful here.”

Samuel Sanchez, 23, and Javier Puga, 22, San Diego

Their first day working the levees, Samuel Sanchez and Javier Puga baked on the towering dirt mounds as temperatures hit 101. Just below them, Tulare Lake spread out on the horizon as far out as they could see.

“We weren’t expecting the type of weather we were gonna be in,” Sanchez said. “I had family from back home [in San Diego] texting us, ‘Oh, it’s 60 degrees outside.’”

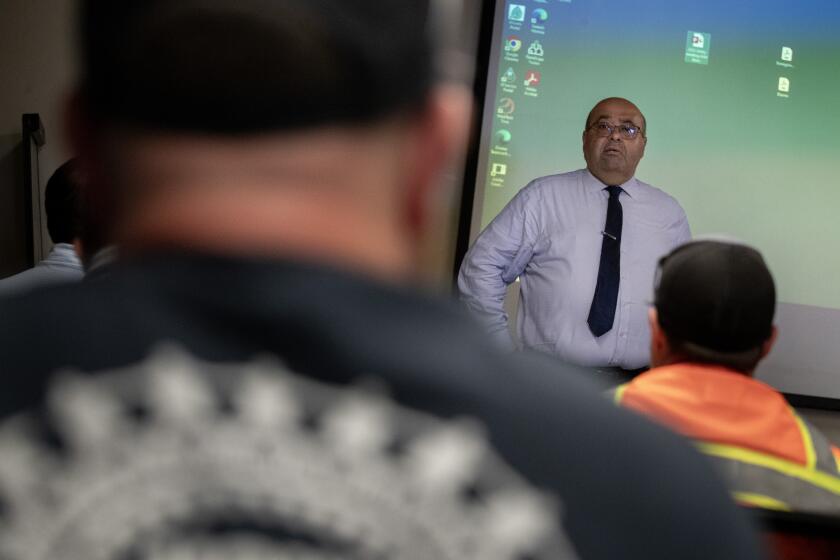

As members of the California Conservation Corps, the two were among more than 100 workers who spent 24 days in May and June fortifying an eight-mile stretch of levee protecting Corcoran and adjacent farmland. The crews, who came in from Norwalk, San Diego and Fortuna, worked 12-hour days, straining against deadline to strengthen the barrier before Tulare Lake drank in what was expected to be epic runoff from a record Sierra snowpack.

They employed a technique called wave wash protection, which involves blanketing the levee with a plastic liner secured with sandbags. The process would help the levees resist the powerful forces of water erosion. In all, they filled up 70,000 sandbags.

Sanchez and Puga, both San Diegans, were fascinated with Tulare Lake’s ghostly presence. It was Puga’s third flood emergency and his second time fortifying a levee. The lake, he said, was unlike anything he’d seen.

“Once you get to the top of the levee, everything you see is water,” he said. “It’s like an ocean. You don’t see nothing but water.”

Standing on the levee, they could see the signs of drowned farmland and roofs of flooded houses and barns. Sanchez said he grasped the magnitude of what had been lost, how livelihoods built over the years were buried in water.

“You could see the urgency of all the farmers to protect all the farms they have left,” he said.

The hours were long, the work grueling, the hospitality unbounded. Sanchez said they met a couple whose home had been flooded, who nonetheless thanked them for their efforts to save Corcoran. Farmers sought them out to express gratitude. Business owners were generous. Some asked if they were Boy Scouts.

“Yeah something like that,” Puga would reply.

“If they needed us to go back to work,” Sanchez said, “we would go back to help them.”

Dave Rinehart, 79, Stratford

For more than 60 years now, Dave Rinehart has worked on tractors in Stratford, from sturdy older rigs to the modern models with computerized equipment.

Stratford sits in the Tulare Lake Basin, but like much of the Central Valley has for years been plagued by drought and a dwindling population. Over the years, while fixing tractors, Rinehart would watch fishermen and boaters drive by in search of the basin’s fabled lake.

“‘You’re in it,” he would tell them. “You’re in Tulare Lake Basin right now because you’re looking at that map, which shows the lake here. There ain’t no water down here.’”

At Stratford Auto, longtime residents gather for morning coffee and conversations. There, Rinehart said, water is a constant topic, many years because there wasn’t enough of it. But recently, with the lake’s resurgence, there’s talk about how there’s too much of it. Still, none of the men are too worried, Rinehart said.

In some ways, it’s reflective of the Kings County resilience. No matter what, people will find a way to keep living, keep working.

“I don’t know why they make a big deal out of it,” Rinehart said of the lake’s return. “I laugh at [the] news when they start talking about that lake.”

Charles Meyer Sr., 82, Stratford

Charles Meyer Sr. is proud to be one of the few family farmers left in Kings County in a valley dominated by industrial-scale operations.

He is a third-generation farmer, taking on land that his grandfather once tilled. But times have hit the Meyer family hard. Once the proud owner of 3,500 acres, his holdings have been whittled down to 1,000, having sold off the rest due to years of drought, market fluctuations and now inflation. Many family operations have been ground down one by one, until they have been forced to sell the land they once hoped would keep their bellies full.

Now, 600 acres are useless, swallowed in the lake’s return. Three hundred acres of land prepped for cotton and another 300 acres of alfalfa on the lake’s northern edge — gone. He estimates his losses at about $600,000, $1,000 for every acre.

Asked about the loss of the land, Meyer said it’s like losing a best friend.

“There’s nothing you can do about it, so it’s no use getting upset,” he likened.

So far, he said, he has not laid off any of his 10 employees. On a recent Monday, they were out in the remaining unflooded acreage, irrigating cotton and cutting alfalfa. He doesn’t know how long before Tulare Lake recedes enough to give him back his land.

But “when it dries out, we’ll need them again,” he said of his crew. “We hate to lay people off and then hire ‘em. My dad used to do that. I quit that.”

These days, his son, Charles Jr., has taken over the family business. On just about any morning, you can find them both out in the fields, picking at the weeds that have sprouted up where they now plan to grow 40 acres of hemp. Meyer sees the move into hemp as a potential remedy for his recent loss. After years of advocacy, including his own testimony up in Sacramento, hemp is a legal crop. He has begun making a CBD oil he thinks could generate an alternative source of revenue. He swears by its healing power for aching joints.

Meyer hopes that the farm can be passed down to his grandchildren one day, and that they’ll be interested in farming and the history of the land.

He just prays there is land to pass down.

Helena Jones, 75, Lemoore

Helena Jones’ daddy traveled by bus to California from Idabel, Okla., in search of work and a better life, part of a wave of Black farmworkers who migrated to California’s Central Valley in the 1940s to work in the fields.

Her family lived in a labor camp, sleeping in milk barns before eventually moving into a shotgun house in Lemoore. By the time she was 4, she had joined her parents in the fields, running ahead of her mother and placing the cotton she picked in neat piles for collection. When she was stung by wasps, her mother spread turpentine on her injury and they pushed on. When she was exhausted, she collapsed on a sack of cotton, worth $3 for every 100 pounds.

Jones lived for a time in San Francisco and raised her children in Visalia, but she always knew she’d end up back in Lemoore, in the district locals call “the island,” bounded by the North and South forks of the Kings River. She eventually married Lennard Jones — Jerry Jones’ brother. The two had dated in high school and reconnected as adults.

“I made it back to my first love and Lemoore,” she said.

When the warnings came that flooding would be bad in Lemoore, she placed sandbags around her home. With flood insurance, she knew she could rebuild. But photos of her husband, now deceased, and her late mother’s personal effects, she could not replace. She packed everything in yellow-lid crates, placing them high on her closet shelves. She wanted to be ready.

“I just prayed,” Jones said. Because she knew if she did have to leave, there might be no road back.

Today, Tulare Lake is slowly receding, and the threat of Lemoore being decimated by flooding has abated. But Jones said she remains concerned about what summer temperatures will mean for the mountain snow — and what next winter will bring.

Her stuff will remain in boxes, she said, so she can stay prepared.

Ernie Smith, 76, Lemoore

Ernie Smith remembers life in Lemoore when the roads were one-lane and cotton was picked by hand. His parents, sharecroppers from Texas, were part of a wave of migrant farmworkers who came to California after World War II in search of work.

Lemoore sits just north of the newly formed Tulare Lake. Back then, Smith’s family, 12 in all, lived in cabins in a labor camp in Stratford, where they spent summers picking cotton for farmer Gus Irons, whose brother guaranteed safe passage for Black tenant farmers who wanted to travel West.

Growing up, Smith said, he didn’t know he was poor. He and his siblings never went hungry, and he never missed a day of school. After high school, he earned his master’s degree and doctorate of education. He and his brother, Tommie Smith, a 1968 Olympic gold medalist in the 200-meter sprint, used to hunt rabbits with their bare hands.

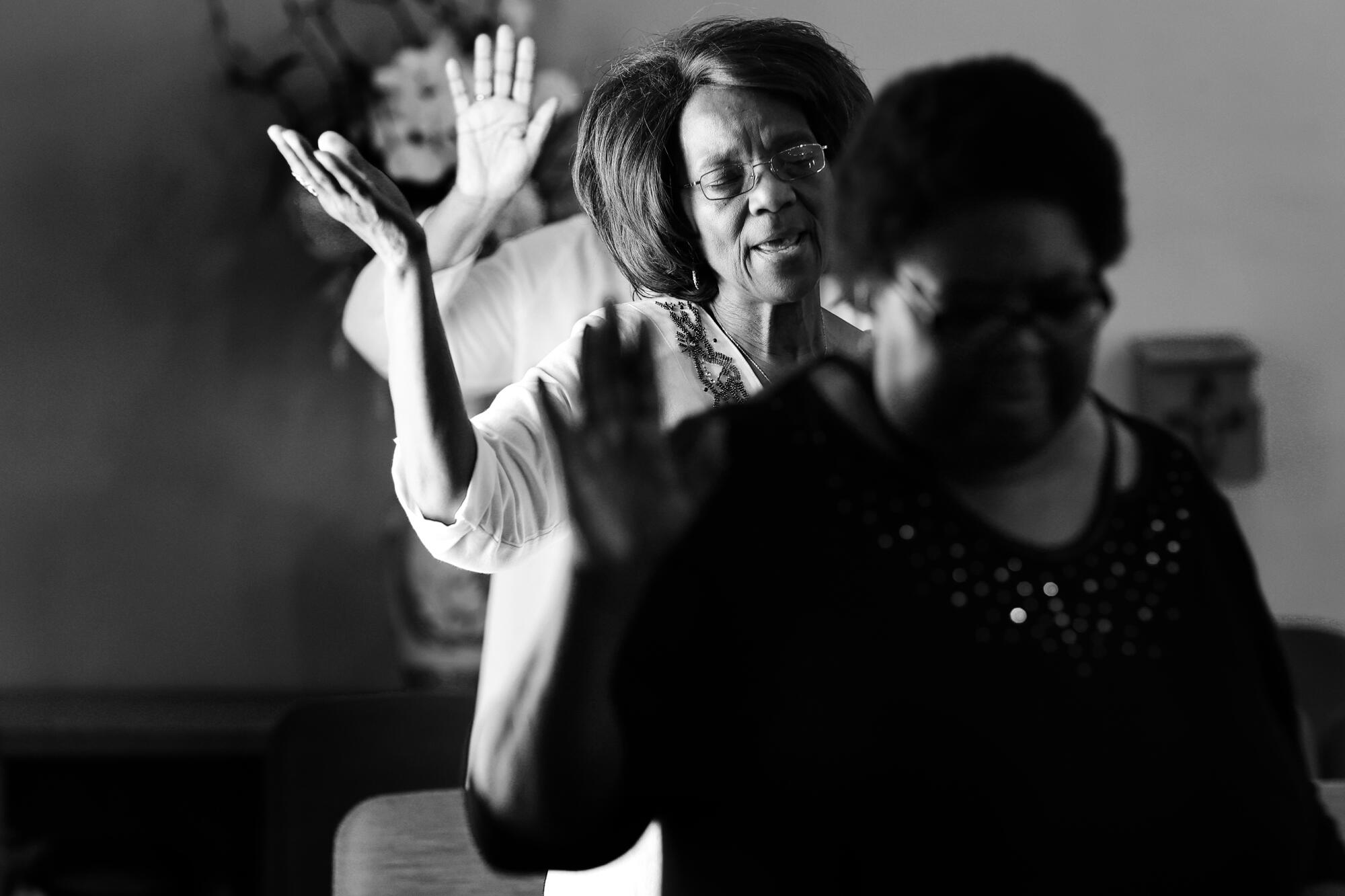

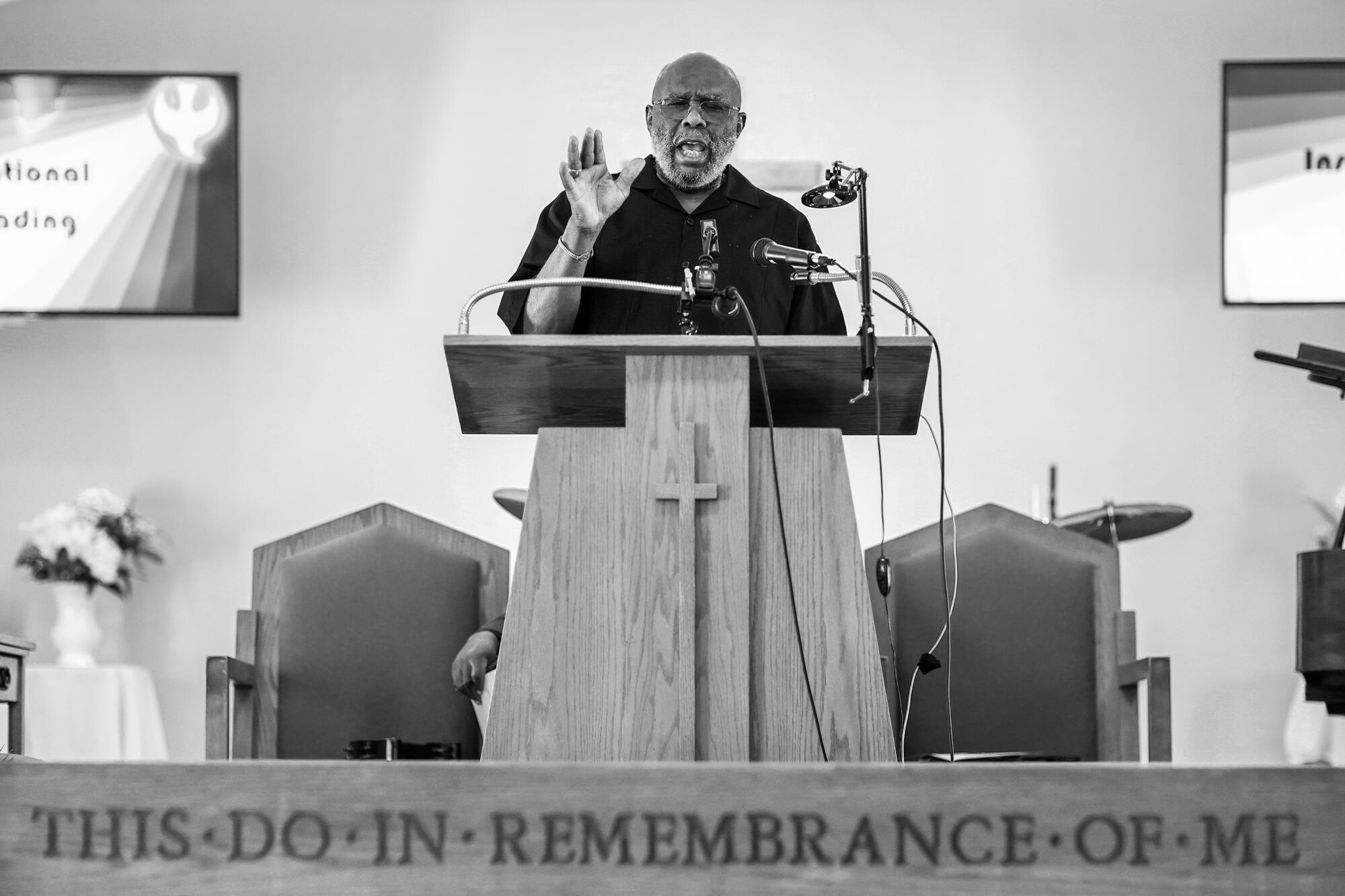

“I was never hungry,” Smith said, sitting in Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church on a Sunday afternoon. “I always had clothes. My mom washed clothes in a tub with a rub board.”

Eventually, his father saved up enough to buy one acre in Lemoore, where he built a family home. Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist began in their family living room and eventually moved into its own building on Jersey Avenue. Smith is now an associate pastor at the church, where he delivers inspirational readings and belts out worship songs to the beat of a tambourine.

Smith can point out where he picked cotton for Irons down by the levee. But the scenes that marked many of his early years are now erased by water. The dilapidated buildings of the labor camp gone.

“That’s where I learned how to work, down at the bottom,” he said. “Planting cotton, picking cotton, chopping cotton.”

His family’s history, like that of many Kings County residents, is tied to the land. He still maintains the acre where his father built their first home. He owns another 35 acres he plans to sell to a man who will grow pistachios.

And like many long-timers in Kings County, Smith has watched his children leave, moving to bigger cities to carve out livelihoods.

But not Smith, who plans to stay in the basin, lake or no lake, until the end of his days.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.