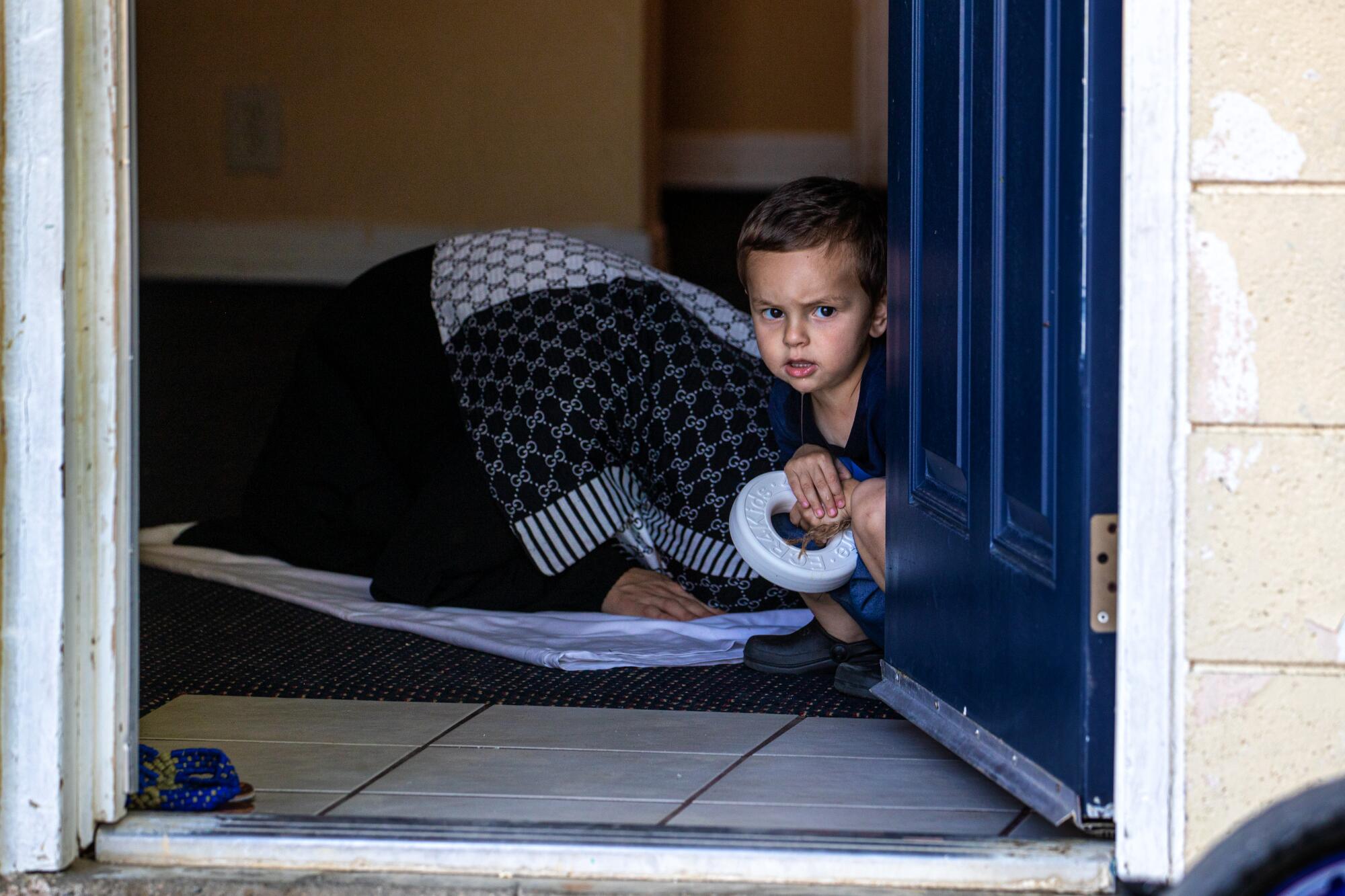

Five-year-old Rood Morancy Siverne huddled close to his mother, who sat tired, yet hopeful, waiting to check in to what would become, at least for a time, their home.

Rood and his parents had fled Chile and made the monthlong trek north through mountains, Panamanian jungles, and the length of Mexico, until arriving at the U.S. border to claim asylum. After yet more travel, they had come to Riverside County and a shelter for immigrants.

Rood quietly stole looks through the office window behind him, where children played outside in a courtyard. Shelter staffers then gave the family a cart brimming with groceries, and the key to a room — their own room.

But there was no time to rest for Rood.

He giggled as he belly-flopped into one of the two twin beds. He hurriedly changed his shirt, pulled up a pair of shorts and ran.

“I don’t need shoes!” he said to his mother in Spanish, sprinting barefoot out the door and waving off a pair of sandals she held.

“The kids want to be outside, they want to run,” said Gloria Gomez, co-founder of Galilee Center, which opened in 2010 and provides lodging, food and clothes to recently arrived migrants. “After being so many days in detention, struggling for weeks, sometimes months, they need that freedom.”

Without a word, Rood joined a game of soccer with three other immigrant children, from Peru, Ecuador, Angola. Such a mix is typical at this shelter, where you’ll hear languages from all over — Spanish and French, Ukrainian and Urdu. Though divided by language, the residents are united by their desperation, their past trauma and their hope for the future.

Galilee Center opened this long-term shelter nearly a year ago to complement services it already provided at a short-term shelter in the desert town of Mecca. For migrants, the Mecca facility was often a brief stop, a chance for a warm meal and a night or two on a cot before continuing on to their destinations.

But after more families arrived at the border in recent years, many with little or no money, Gomez said she saw a greater need.

Housing people up to 90 days, the long-term shelter serves asylum seekers who arrive without a sponsor or a place to go, or those who had a sponsor that suddenly backed out. In operation for nearly a year, the motel-turned-shelter is the only long-term shelter for asylum seekers near the border in California, Gomez said, and only the second long-term shelter for migrants along the more than 1,900-mile southern border.

“When people arrived in buses, a lot of people had no place to go and the employees asked, ‘Are we kicking them out? With kids? With babies?’” Gomez said. “I thought, enough is enough.”

A Times reporter and photographer visited the shelter in Riverside County, but officials asked that its location not be disclosed, citing the safety of asylum seekers.

With more than 30 rooms, the center on a recent weekday housed more than 50 adults and 30 children from across the globe. Even though some didn’t speak the same language, small kids pedaled, laughed and raced down the corridor on tricycles. Another group of kids, including Rood, ran after a soccer ball.

Standing at the doorway of the family’s room and watching his son play, Rood’s father, Beginne Morancy, 38, recounted how he and his wife, Sandia Siverne, 30, fled Haiti seven years earlier. They left to escape rampant violence in the country, Morancy said, and they found their way to Chile.

There, the couple learned Spanish, took odd jobs to make ends meet and had their son, Rood.

But earlier this year, while Rood was playing with neighborhood children, much like he was doing now, he ran and crashed into one of the kids.

“They were friends, and he got hurt,” Morancy said. “They hurt each other while playing.”

Morancy said they apologized to the boy and his father, but what seemed like just a playground accident took a turn.

“We exchanged words, but he started to threaten my child,” he said.

The exchange nearly came to blows, but Morancy hoped things would blow over with time. Instead, the threats continued. Then one day, the man walked out with a knife, threatening Rood and his parents if the boy went outside to play with the neighborhood kids again.

Morancy said he reported the incident to authorities, but they did nothing.

“He’s from Chile, and I’m not from there,” he said. “He knew all the neighbors, and I didn’t know anybody. The country is not my country.”

Fearful, the family fled — again.

“I had no choice,” Morancy said.

Family savings paid for crowded buses and cars north through South America — and for bribes to get through police and military checkpoints in Mexico.

“It’s very expensive, very hard,” Morancy said.

Since setting out, there had been no time for rest, and no time for Rood to play, until now.

The family plans to head out to New York, he said. He’s not yet sure how, but his family is safe.

“We’re happy,” Morancy said.

Since its inception, staffers said, the long-term shelter has been like a microcosm of the country’s immigration system, reflecting the confusing, rapidly changing rules that migrants must navigate and the forces that compel them to flee their home countries.

Brazilians and Venezuelans poured into the shelter when instability rocked their countries. After Afghanistan fell to the Taliban in August 2021, the shelter saw a new surge of asylum seekers.

The daughter of a Guatemalan dictator convicted of genocide is running for president, raising questions about the nation’s memory of a brutal civil war.

Last year the bulk of the asylum seekers came from Latin America, including Cuba, Colombia, Peru, Venezuela and Nicaragua. This year, the shelter has seen hundreds of people from Peru, Colombia and Ecuador, but also large numbers from Angola, Afghanistan, Russia and Ukraine.

“When I came to this job I thought I would just find people who would come from Spanish-speaking countries, but then you start seeing a lot of people who speak Portuguese, or Persian, or another language,” said Laura Pozar, an intake leader at the shelter.

When a stream of families suddenly arrived from Eritrea, an African country with nine major languages, staffers couldn’t fine a phone app to translate. Eventually, some families from Somalia were able to help.

“Sometimes Google Translate doesn’t have all the languages we need,” Gomez said. “Sometimes we’re not sure if we’re translating the right thing because they sometimes look at us like, ‘What are you saying?’”

The shelter has also had to shift in other ways. Some families don’t eat pork, others are vegetarian.

Other needs are universal, Gomez points out — water, rice, vegetables. All families are given ingredients to make bread. No matter their point of origin, she said, most of them seem to find some comfort in making bread.

And all the kids want balls to bounce, tricycles to ride.

In one corner, three kids jumped off their trikes and squatted to watch a cartoon on a cellphone.

A boy poked his head into the motel room that’s been turned into an office. “Can we borrow a basketball ball?” he asked.

“Watch out for the windows,” Gomez replied, as a worker handed the boy a ball.

“The kids want to be outside, they want to run. After being so many days in detention, struggling for weeks, sometimes months, they need that freedom.”

— Gloria Gomez, co-founder of Galilee Center

Last year, the Galilee Center provided assistance to more than 33,000 people, Gomez said, including those who stayed at its short- and long-term shelters. This year, the nonprofit has seen more than 7,000 so far. About 1,000 have stayed at the long-term shelter.

As Gomez walked through the shelter, asking people if they need food, clothing or help, a woman came up to her. The woman asked to be identified as “Celina,” fearing that speaking publicly could affect her immigration case.

Celina, her partner and his brother fled Ecuador after a criminal group demanded $3,000 every two weeks to provide “protection” for their small store. When they ignored the demands, knowing they could never afford the payments, her partner’s brother was beaten. It was, they were told, their only warning.

Each spring, hundreds of gay cowboys gather in Zacatecas for a convention that celebrates sexual freedom and romanticizes Mexico’s rural past.

When they turned themselves in to border officials in Calexico, Celina was released the next day while her partner remained in custody. His brother was sent to Mississippi.

Staff at the shelter helped her pin down where her partner was being held and 15 days later, Gomez assured her he was on his way that day to the shelter.

Like many adults at the shelter, Celina was nervous, running out of money and worried, the stress showing on her face. In Mexico, she said, she and her partner were stopped repeatedly by law enforcement and military officials , who demanded bribes to let them continue north.

The money she had left, Celina said, was a roll of bills she rushed to put into a plastic bag and stuffed into a soda can when police stopped the bus. Their possessions, and the bus, were ransacked, she said.

With just a little bit of money left, and on her own, Celina said she feels there’s little to no room for her to make mistakes if she and her partner are to make it.

She has not received official permission to work, she said, but found a job as a cashier at a local restaurant. It’s risky, but her court date is in two years, so how could she and her partner make it until then, she asked?

She was anxious to see him again, she said.

“I miss my country,” she said. “If I wasn’t in danger, I’d go back.”

Many families find themselves in similar circumstances, Gomez said. And many of them have lost loved ones or suffered traumatic experiences during their treks to the United States, she said.

Joao Mantijila, who is requesting asylum from Angola, said he was stopped so often by police in Mexico he decided to cut a slot into the side of the sole of his shoe. Inside, he hid the last bills he had left.

He sat on a plastic chair, under the shade of a tree, resting and checking his phone for messages while children chased each other around the tree.

“Police in Mexico come into buses, ask for documents, demand money, bribes and threaten you at gunpoint,” he said. “They’d yell, ‘Give up the money, give up the money.’ It was terrible.”

Lutonadio Maria Manuel, sitting next to him, frowned and nodded in agreement. She traveled with her granddaughter through Mexico after her daughter was killed in Angola, she said.

Then she bowed and parted her hair to show how she hid her money deep inside of it.

On a recent afternoon, adults used the motel Wi-Fi to reach families in their home countries or friends and relatives in the States. One mother from Afghanistan rocked her 45-day-old baby at the doorway of her room.

Celina returned to the reception desk to check about her partner. She didn’t want to miss him when he arrived. She had changed clothes and put on makeup just for him.

He’s en route, the staff assured her.

Later, Celina checked in one more time about her partner, and shelter staff said he was set to arrive at any moment. Could she wait a few more minutes?

She couldn’t. She’d found a job in town, and it was only her second day and Celina didn’t want to risk losing it. Every dollar she earned, she said, put her and her partner on the path to leave the shelter and be on their own. There was no room for mistakes.

In the courtyard, the sun was starting to set and a cool breeze was settling in. Adults stepped outside to escape the heat of the stoves warming up dinner in their rooms.

Kids continued to run and play and laugh. There were still a few minutes of daylight left, and plenty of time to play.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.