The advertisements spring to life with bright colors and smiling, young women, usually Black or Latina, celebrating the arrival of desperately needed cash.

“Cha-ching!” the website of one smartphone app declares, displaying a curly-haired mother and child who look to be jumping for joy. “It’s payday all day, everyday.” Funds are available “in minutes” to help pay for groceries, rent and family celebrations without “mandatory fees” or interest, it says.

For the record:

3:29 p.m. May 31, 2023An earlier version of this article identified Dave as the cash app that sent Melissa Burrola the messages requesting tips that were displayed in accompanying screenshot images. Those messages were from MoneyLion.

7:35 a.m. May 25, 2023An earlier version of this article identified the senior policy counsel for the Center for Responsible Lending as Aaron Kushner. His name is Andrew Kushner.

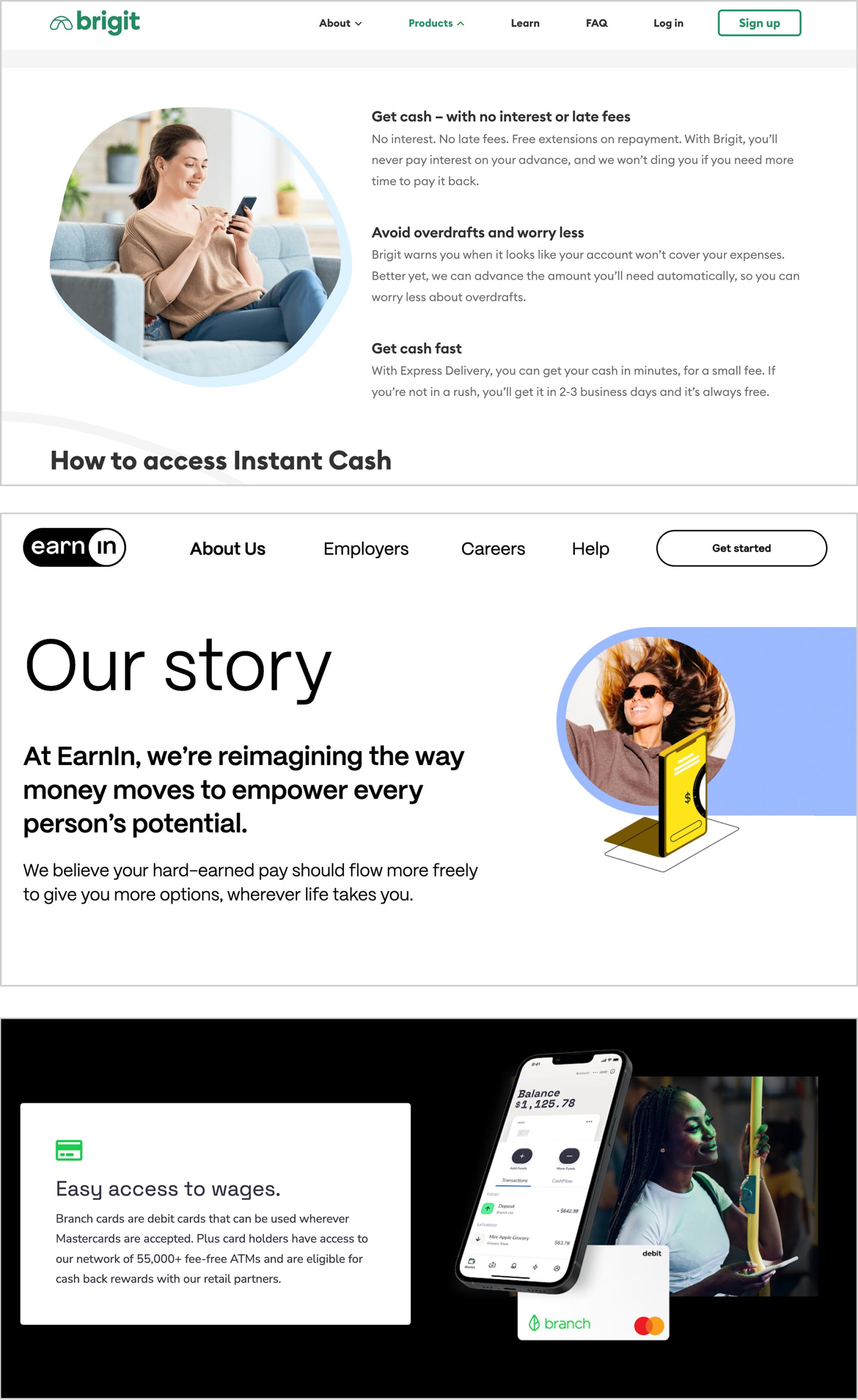

Another app features a photo array of six female workers and one man laboring in call centers, nursing homes, restaurants and retail. “Pay bills on time, with no late fees, no overdraft fees and no need for payday loans,” it says.

A third app, backed by actor Ashton Kutcher and NBA star Kevin Durant, pushes its product with a TikTok video where a young Black woman is approached while walking down the street in jogging shorts. “What if I told you I could get you some money right now?” she’s asked. Seconds later, when she has it, she exclaims: “Oh, my god!”

These apps — EarnIn, Daily Pay, and Brigit — are all examples of a fast-growing product called Earned Wage Access, which the U.S. Treasury Department said advanced $9.5 billion to consumers through 56 million transactions in 2020 and continues to grow.

Similar to a high-cost payday loan, these apps offer workers emergency cash ahead of proven, upcoming paychecks. Like payday loans, they are disproportionately used by women, especially women of color and single mothers.

Unlike traditional payday loans, which are most frequently taken out by the poor, Earned Wage Access ”users are college-educated, middle-class, full-time workers,” according to a report by FTI Consulting, which surveyed three companies’ customers. The typical recipient makes $50,700 a year but is still “living paycheck-to-paycheck,” the firm found. Nearly two-thirds of users were women and half were people of color.

The companies operate in a legal gray area that allows them to function much like a payday lender but without the consumer-protection rules that govern those businesses.

The federal government also does not regulate them like banks, and their products are largely free from scrutiny under the Truth in Lending Act, thanks to a legal opinion issued by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau during Donald Trump’s presidency. Consumer advocates say that, while the companies’ claims of “no mandatory fees” and “no interest” may be technically accurate, their true sticker price is high and abuses are rife.

In California, where many of these companies are based, regulators have begun to probe their practices. In March, the state’s consumer protection agency, the Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, released a report that found Earned Wage Access apps charged the equivalent of an annual average interest rate of between 331% and 334%.

The agency reached its conclusion after analyzing data from more than 5 million transactions from seven companies operating in the state. Rather than serving as an occasional stopgap, the department found workers used them habitually: an average of nine times per quarter, or 36 times a year. The agency has proposed rules that would make California the first state in the nation to regulate the product.

“It’s a trap,” said Melissa Burrola, 46, a single mother of three adult children, who makes $19.50 an hour at a nonprofit that provides free food and clothing to the poor in St. Paul, Minn. “I just want to get out of it.”

Burrola turned to three different earned wage apps when her car broke down last September, cobbling together $500 for repairs so she could get to work. Each of the apps charged her a fee. One of them, Dave, a Los Angeles-based “neobank” backed by billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban, also encouraged her to tip the company on top of a $6.99 fee she paid to get cash instantly. The default tip was set to $6 on a $100 advance.

“People are struggling,” said Andrew Kushner, senior policy counsel for the Center for Responsible Lending, an advocacy group. “If you get money this week, that’s less money to pay your expenses next week and you’re even worse off because of the fee.”

California’s proposed rules, published in March, would regulate app-based advances as loans and cap the interest rates and fees they could charge at the same levels as other financial products.

“We want to be sure we are doing everything we can to make sure people are being treated fairly,” said Suzanne Martindale, who heads the agency’s consumer financial protection division.

The industry strongly opposes California’s proposed rules. EarnIn, which is based in Palo Alto, mounted a social media campaign to encourage its users to email state regulators, lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom ahead of a May 17 deadline for public comment.

A message EarnIn suggested its customers send state officials says the app “allows me to manage my finances and helps me avoid having to choose which bills to pay, just because my paycheck hasn’t landed in my account yet .… Having access to my money in real-time also saves me from overdrafting and even allows me to proactively put away some money for a rainy day.”

A spokesperson for the consumer agency said it had received thousands of comments on its proposal to regulate cash apps — a torrent compared to the hundreds it typically gets.

At the heart of the debate is the way Earned Wage Access companies generate revenue. Rather than charging interest for money owed, many offer a free version of the app that features financial planning tools but only provide cash advances to customers who pay for a subscription. For example Brigit, the app backed by Kutcher and Durant, charges $9.99 a month for a “plus plan” for people who “need cash ASAP.” Representatives of Brigit did not respond to multiple inquiries.

Others, including EarnIn and Dave, offer free advances for customers who are willing to wait up to three days for a bank transfer but charge a fee to those who want cash immediately.

The apps also ask users to pay “tips,” as they would for an Uber driver. Unlike Uber tips, however, those on paycheck advance apps don’t go to a worker. They bolster the company’s bottom line, state regulators note.

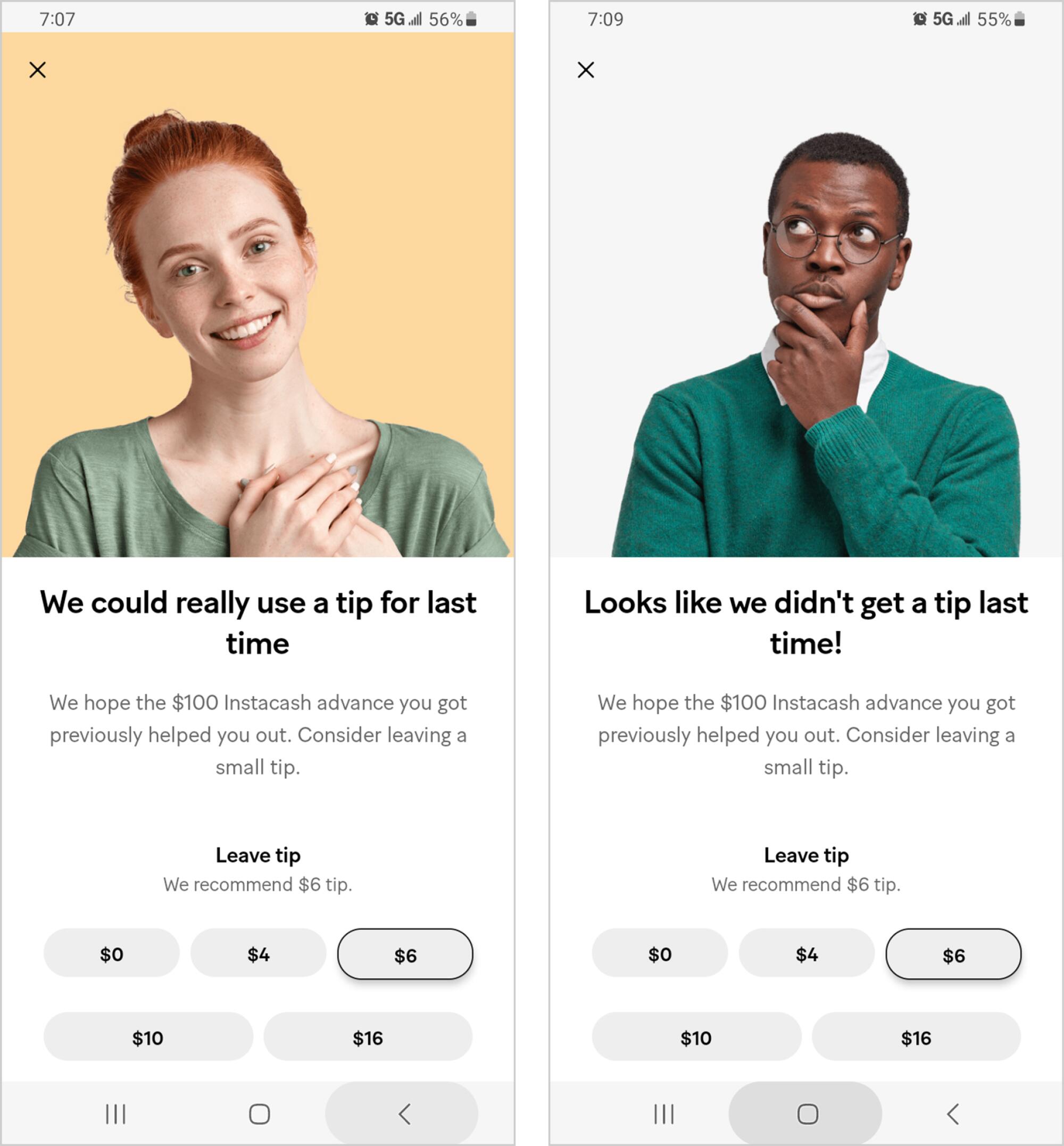

California regulators say those tips may not be entirely voluntary. In detailed reasoning published as part of its proposed rules, the state’s financial protection agency said it found many examples of apps setting default tips and “using other user interface elements to make tipping hard to avoid.”

Companies also made it difficult to set a $0 tip or did not advertise that a particular payment is optional. There were also examples of apps “disabling a service if a borrower does not tip ... [and] .. claiming that tips are used to help other vulnerable consumers or for charitable contributions.”

The financial app Dave promises its customers freedom from expensive bank overdrafts. But for almost all of its users, its services are hardly free.

“Their whole business model is predicated on this attempt to find a technical loophole in the definition of a loan under California law,” said Kushner of the Center for Responsible Lending.

“It’s dishonest and deceptive,” said Gladys Washington, a 63-year-old in-home caretaker from Philadelphia who gets cash advances from EarnIn multiple times a month.

Washington scoffed when told the company was arguing its products could not legally be described as a loan. “If you have to borrow something and have to pay it back, that’s a loan,” she said. “I don’t see how that could be any different.”

Washington said she’s found it difficult, but not impossible, to avoid paying for tips on the EarnIn platform: “You have to hit ‘minus’ over and over again,” she said.

Washington said she regularly pays the company’s “Lightning Speed” fee — usually $3.99 per transaction — to get cash immediately rather than wait to get the advance free of charge.

“If you need the money now and you have to wait two days otherwise, that’s not free,” she said, rejecting EarnIn’s claim that it charges “no mandatory fees.”

Burrola said she felt pressured to tip. “We really could use a tip for the last time,” read one message from a cash app called MoneyLion. It included a photo of a young white woman holding her hands on her heart.

One time, when she chose not to tip, a picture of a bespectacled African American man appeared on the app. “Looks like we didn’t get a tip last time!” says the text beneath the photo. “We recommend [a] $6 tip.” A MoneyLion spokesperson said the company declined to comment.

Another time, Burrola said, the app Dave told her a tip would help a charity called Feeding America with which Dave has partnered. The frequent fees and the tips cut into Burrola’s upcoming paychecks, leading her to take more advances, incur more fees and fall behind.

“It just kept going,” she said. Eight months later, fees from the apps have compounded her financial troubles and she remains on a hamster wheel of cash advances and charges.

A spokesperson for Dave declined to comment for this report, but noted the company offers fee-free advances to customers willing to wait for the money or have it deposited on a company debit card. The company said tips are entirely voluntary and that any customer who wants a refund need only contact customer service.

Burrola said she was unaware that tips could be refunded. “They sure do not tell you this,” she said.

Women have been more likely than men to use these services in part because they are less likely to have access to bank products, such as home equity loans and credit cards, according to a 2021 research report from Arizent, the publisher of American Banker.

Under the proposed California regulations, tips would be treated as charges under the law, count against maximum fees allowed and be subject to strict limits.

Even as California looks to impose restrictions, industry-backed legislation has been introduced this year in Missouri, Mississippi, South Carolina and Vermont, using model language from the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council. The model legislation says a company could be said to not charge mandatory fees and accept tips “as long as the Provider offers the Consumer at least one option of receiving Proceeds at no cost.”

California regulators say they are reviewing the mountain of comments they received on the draft rules and hope to finalize regulations by the end of the year. Regardless of which approach they take, the rising cost of living will continue to drive the most financially vulnerable consumers to the apps — a trend some of the companies are banking on.

In a presentation Dave shared with investors for an earnings call in May, company executives described their target market as 37 million Americans who are “financially vulnerable” because their spending outstrips their income, they have minimal savings and frequently overdraft their bank accounts.

Another 139 million Americans, the presentation showed, are “financially coping” because they have overdrafts “several times a year” and have “insufficient long term savings.” Both these groups are growing in number, the company reported, providing a “large addressable market exhibiting solid growth trajectory.”

This article is published in partnership with the Fuller Project, a global nonprofit newsroom dedicated to reporting on issues impacting women.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.