‘Nature gave us a lifeline’: Southern California refills largest reservoir in dramatic fashion

Following a series of winter storms that eased drought conditions across the state, Southern Californians celebrated a sight nobody has seen for several punishing years: water rushing into Diamond Valley Lake.

The massive reservoir — the largest in Southern California — was considerably drained during the state’s driest three years on record, with nearly half of the lake’s supply used to bolster minuscule allocations from state water providers.

But an extraordinarily wet winter allowed officials from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California to turn on the taps in Hemet once again. Water transported from Northern California roared out of huge concrete valves Monday and into the blue lake at 600 cubic feet per second — marking an incredible turnaround for a region that only months ago had barely enough supplies to meet the health and safety needs of 6 million people.

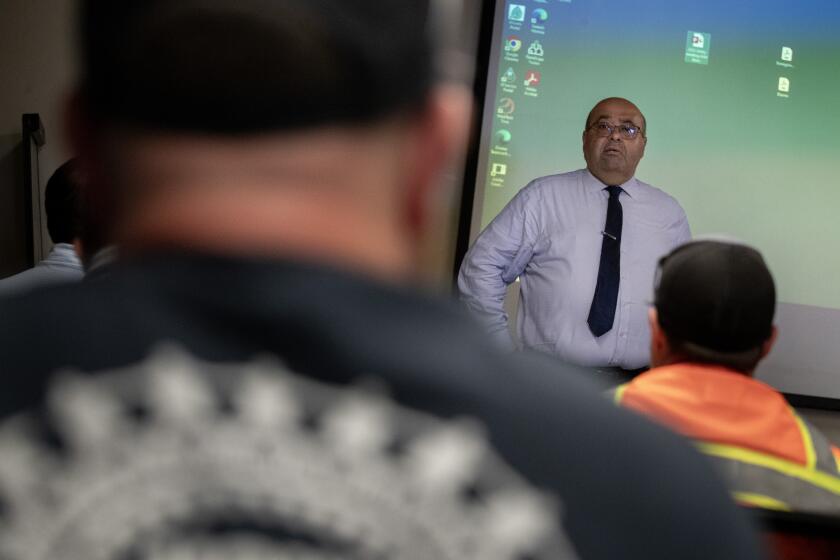

“Nature gave us a lifeline in the face of climate whiplash,” said Adel Hagekhalil, MWD’s general manager, from the shore of the refilling lake. “We need to take this lifeline, replenish our resources, but continue to work and plan ahead.”

Newsom’s decision to rescind some of the most severe restrictions comes after drenching storms eased extreme drought conditions across the state.

Officials said the gushing spigots should be able to refill the 810,000 acre-foot reservoir to its full capacity by the end of the year. An acre-foot is approximately 326,000 gallons.

But although the state’s abundance of water is the silver lining of a deadly and devastating winter storm season, it’s also a reminder of how delicate conditions are in the face of California’s changing climate. Rapid swings from extreme wetness to extreme dryness are becoming more common, and the lake will undoubtedly be needed for dry times again.

“Just because we’re now seeing some rain — lots of rain — does not mean that we can let up,” said Heather Repenning, vice chair of MWD’s board. “I know that’s not what everyone wants to hear, but that is reality. We must rebuild our reserves and reduce our demands in the long term to ensure we keep this water in storage for the drier days ahead.”

Diamond Valley Lake is a “backbone” of Southern California’s water storage system, Hagekhalil said. Its reserves can be routed to almost all of MWD’s service area during dry times, and without it, the last three years of drought would have been even more challenging for the region’s residents.

The $2-billion, 4.5-mile-long reservoir was built nearly three decades ago and holds twice as much water as all of the region’s other surface reservoirs combined. It has continued to act as a buffer against drought, and against the looming threat of earthquakes and other emergencies that could cut off Southern California’s supply.

“When things go really bad, this is the one that saves our system,” Hagekhalil said.

The mood on Monday was joyous, however, as water poured into the reservoir from the State Water Project — a vast network of reservoirs, canals and dams that acts as a major component of California’s water system.

Last week, officials from the Department of Water Resources said the state’s soaking storms and record-deep snowpack had boosted supplies so significantly that they were able to increase State Water Project allocations from 35% to 75% for their member agencies, which together provide water for about 27 million people.

Bone-dry conditions last year saw the State Water Project allocation at just 5% for the second year in a row.

Diamond Valley Lake, an “inland ocean,” is Southern California’s prime defense against drought.

Winter’s bounty also enabled Gov. Gavin Newsom to scale back emergency actions tied to the drought, including calls for a 15% reduction in water use and a requirement that urban suppliers activate Level 2 of their water shortage contingency plans, indicating a shortage of 20%.

The MWD similarly peeled back some of its most stringent restrictions this month, including requirements that member agencies limit outdoor watering to one day a week or reduce their overall use.

However, the larger trend is toward “hotter and drier conditions,” said Wade Crowfoot, California’s natural resources secretary. He added that research indicates that 10% of the state’s water supply will be lost to thirstier soils and a more evaporative atmosphere by 2040.

“From my perspective, there’s no going back to normal — it’s adjusting to a new normal,” Crowfoot said. That includes “understanding that we’re going to have these long, hot droughts that are punctuated by very intense wet winters. Increasingly, we need to adjust our infrastructure, our management, to capture water during wet winters like this for use during longer drought periods.”

Those efforts include expanding the state’s water storage capacity, improving its groundwater recharge capabilities and accelerating wastewater recycling and brackish desalination projects, among other items outlined in Newsom’s Strategy for a Hotter, Drier California.

Also included in the strategy are some more controversial projects, including plans to build a giant tunnel to move water beneath the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and plans for a new reservoir north of Sacramento — both of which have sparked opposition from environmental groups.

MWD officials pointed to Diamond Valley Lake as an example of the foresight needed for big projects in the future.

But the agency must also improve its present ability to move water throughout its system. Some parts of its coverage area — including portions of Ventura and western Los Angeles County — are almost entirely dependent on state supplies, yet the MWD has limited means of delivering water to them from Diamond Valley Lake, Hagekhalil said.

“I want to make sure that every drop we have in our system is able to move anywhere in our system,” he said.

The statewide snowpack record also hangs in the balance as another storm is poised to bring even more snow to the Sierra.

With many projects in various stages of development and completion, officials on Monday also applauded Southern Californians for their herculean conservation efforts. Though the region’s population has grown by 5 million people since 1990, there has been “almost no growth in overall water usage,” Crowfoot said.

However, officials noted that Southern California could soon be facing considerable cuts from its other major supply — the strained Colorado River system — and should maintain its ethos of conservation.

Still, Hagekhalil breathed a clear sigh of relief as the reservoir refilled behind him Monday.

“It doesn’t take much to get us into the other side of whiplash,” the general manager said. But “we’re in good shape right now, and probably will be in good shape the rest of this year, and probably next year.”

From a catwalk high above the output valves, MWD operations and maintenance manager Scott Reierson said it was a rare day at work.

“This is super cool — we don’t get to see this too often,” he said above the roar of rushing water. “We only get to do this once in a blue moon.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.