Man behind iconic USS Midway Museum to retire

SAN DIEGO — The ship wasn’t even here yet when John “Mac” McLaughlin became the founding president and CEO of the USS Midway Museum in December 2003.

It was a dream, really, the plans so tenuous that organizers had to have $500,000 set aside to cover the cost of towing the mothballed, nearly 60-year-old aircraft carrier away from San Diego if the museum flopped.

It didn’t flop. It flourished into one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions — more than 18 million visitors and counting — and an icon on the downtown waterfront. Now, almost 20 years later, McLaughlin has decided it’s time to walk away. He retires Wednesday.

“Sometimes you just know,” the almost 72-year-old former Navy rear admiral said. “It’s time to make way for someone with more energy than this old guy who can see the Midway into its next chapters.”

McLaughlin said he and his wife of 46 years, Nora, are ready to “slow the pace down a bit” and are moving to a small town in the Blue Ridge Mountains in South Carolina.

He’ll leave behind the most successful floating naval museum in the world, an attraction on par with the San Diego Zoo, SeaWorld and Balboa Park in the rankings of various visitor guides. According to Tripadvisor, it is the fourth most popular museum of any kind in the U.S.

“Mac came to San Diego on a wing and prayer that this carrier thing might be a success, and somehow he mustered the courage to do it,” said John Hawkins, a member of the museum’s organizing committee. It spent 12 years navigating federal, state and local regulations while the decommissioned vessel sat in a Navy shipyard in Bremerton, Wash.

McLaughlin had just retired from the Navy and moved to San Diego with his wife, a Chula Vista native, when he was approached about running the Midway.

A former helicopter pilot who had landed a time or two on the 1,000-foot-long carrier, he had a fondness for the ship, and for the idea. San Diego is the birthplace of naval aviation. The first U.S. aircraft carriers were home-ported here.

But the prospects were daunting.

“We had no money, a lot of debt, and no revenue,” he recalled in an interview Friday. “No electricity, no water, and no exhibits. We didn’t have anything.”

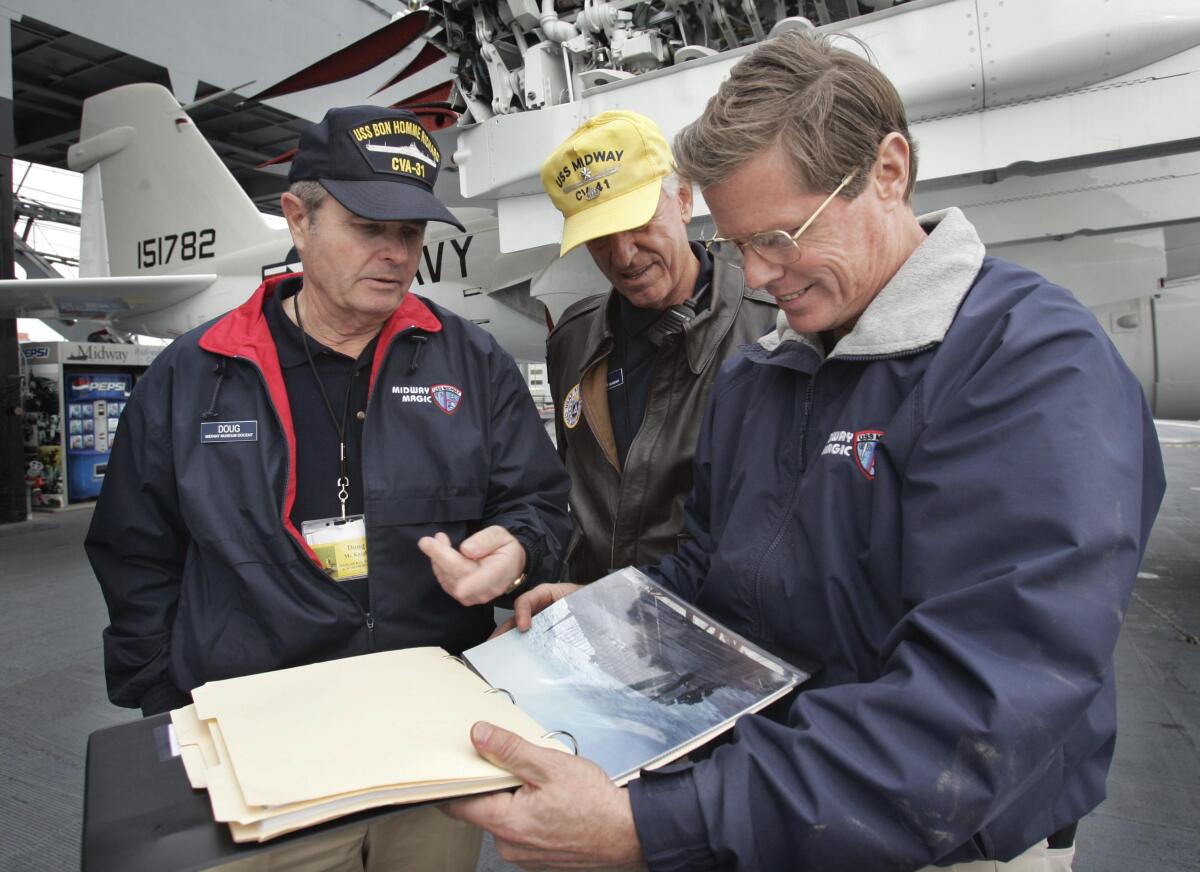

Except volunteers. And that made all the difference, he said. Volunteers found four airplanes to put on display. Volunteers helped scrape away years of rust and mounds of bird droppings. They painted and polished. And volunteers came aboard as docents, to tell the kind of personal stories that turned the museum into a piece of living history.

Somehow it all came together in six months, and the Midway opened to the public on June 7, 2004. “We’ve got to earn our place on the waterfront,” McLaughlin told the Union-Tribune that day. “You earn it by providing value and service to the community.”

Within the first hour, 500 people had bought tickets. That was a sign of things to come.

Museum organizers hoped to draw 440,000 people the first year. They got almost double that, and never dropped below 800,000 until COVID hit. In 2012, annual attendance hit 1 million for the first time.

That success has allowed the museum to add a variety of attractions, including almost 30 restored planes and 60 exhibits, and to be open every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas.

The ship also hosts thousands of schoolkids annually for educational programs and sleepovers. It’s been the site of hundreds of private events yearly — fundraising galas, military ceremonies, memorial services — and scores of public gatherings, including an annual showing of the movie “Top Gun.” A college basketball game between San Diego State and Syracuse was played on the flight deck. “American Idol” has filmed episodes there.

“Mac carried out a challenging task in transitioning us from a raw ship into a functioning public attraction, and then building it up into a cherished community asset,” said Karl Zingheim, the Midway’s longtime historian.

McLaughlin said that’s what he is proudest of, “that most people in San Diego now feel the USS Midway is part of the city landscape.”

He gave the credit to others. “So many people were behind us, had their oars in the water,” he said. “The list of people who made this all happen is very long.”

Museum officials have picked his successor: Terry Kraft, a retired Navy rear admiral whose 30-plus years in the service included stints commanding an aviation squadron, ship and aircraft-carrier strike groups, and overseas shore facilities. He also worked in management for defense contractor General Atomics for almost a decade.

As a flight officer, Kraft received the Distinguished Flying Cross during Operation Desert Storm in the early 1990s for combat missions flown off an aircraft carrier — the Midway.

One of his first major projects will be development of the Midway’s long-promised, $60-million public park on Navy Pier that will include a bayfront promenade and an amphitheater. Work on Freedom Park is expected to begin next year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.