Unions and environmentalists push for California referendum reform

California’s influential labor unions, government watchdogs and environmental advocates repeatedly accuse corporations of lying to voters in campaigns to reverse state laws and thwart the progressive Democratic agenda at the state Capitol.

Now they plan to do something about it.

Assemblymember Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) is introducing a proposal this week to reform state elections law by making it more difficult for campaigns to mislead voters when circulating petitions to qualify a statewide referendum. The bill marks the latest showdown in a proxy war between labor and business at the state Capitol and could become one of the most high-profile political fights in California this year.

“It is a very old process, and over time its original intent and utility has been subverted by a small, disgruntled, well-funded, well-powered set of interests that often undermine the collective will of the people of California,” Bryan said.

Assembly Bill 421 would establish new government oversight of signature collection, require more transparency about the groups funding referendum campaigns and mandate that at least 10% of petition signatures must be obtained by unpaid volunteers. The sweeping legislation would apply the new rules to referendums and extend to initiative campaigns that seek to repeal or amend a state statute within two years of the law taking effect.

The Service Employees International Union of California and other proponents of the bill say it’s necessary to realign California’s referendum system with its founding objective from 1911: to provide a mechanism through direct democracy for voters to counter the influence corporations held over state government.

California voters in 2024 will decide whether to keep a law to require buffer zones around new oil wells as corporations use referendums to challenge progressive policies.

Today, unions and progressive advocacy groups carry more sway over lawmakers than a century ago, and businesses often struggle to protect their interests at the state Capitol.

Advocates for the legislation say over time the referendum system has become less of a tool for the people of California to check their Legislature and instead an opportunity for wealthy businesses to stall and reverse state laws passed by a supermajority of Democrats to address poverty, protect public health and benefit the environment.

Over the last several years, companies that make cigarettes, manufacture plastics and operate bail bonds firms launched multimillion-dollar campaigns to gather petition signatures to qualify voter referendums that challenged laws that hurt their business model.

The California Chamber of Commerce has pushed back on the need for referendum reform and argued that companies rarely launch campaigns against laws. The chamber has compared the half-dozen referendums that qualified for the ballot over the last decade with the thousands of laws enacted by the Legislature and governor in California over that same time period.

The strategy, however, has already paused two major progressive laws this year until the November 2024 ballot.

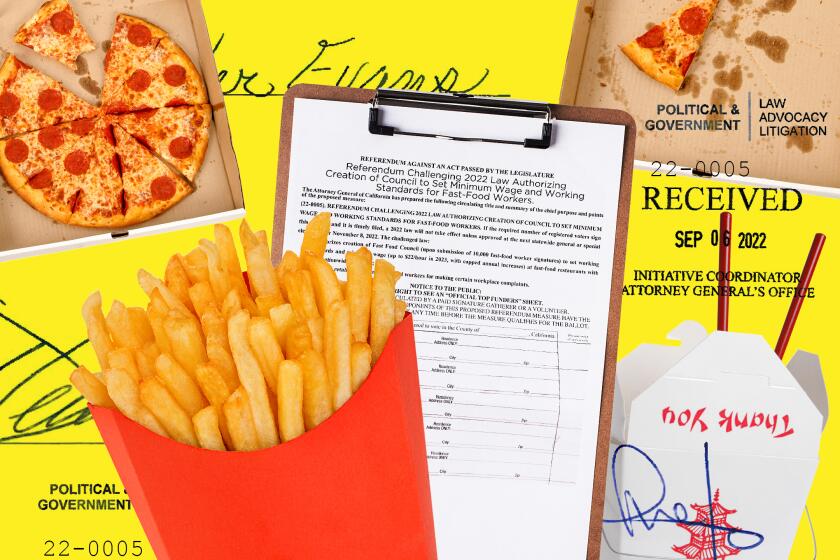

In January, the secretary of state announced that fast food companies had collected enough signatures to force a referendum on a California law meant to boost wages for restaurant workers. Last month, oil companies qualified for the ballot their effort to overturn an environmental safety law that would ban new drilling projects near homes and schools.

The oil setbacks legislation passed in 2022 after years of grassroots organizing and several failed attempts in the Legislature. Almost immediately, the industry began trying to mislead voters about the law and to turn them against a policy that would protect the health of disadvantaged communities, said Melissa Romero of California Environmental Voters.

“This is a really disgusting abuse of power, and it is an example of one of the ways that corporations currently act as if they’re above the law just by the nature of having enough money to do whatever they want,” Romero said. “And voters are sick of it.”

To ask voters to reverse a law on the next statewide ballot, proponents of a referendum must obtain signatures from 5% of the number of voters in the last gubernatorial election. Political campaigns often hire firms to circulate petitions and pay people per signature collected. Many signature gatherers travel from other states.

California voters complain that canvassers for a measure to repeal a law expanding protections for fast-food workers lied about the effects.

A key provision of AB 421 would require that unpaid volunteers gather at least 10% of signatures needed to qualify a referendum on the ballot.

“A fundamental part of participatory democracy is to have people who genuinely care as opposed to people who are paid to gather signatures at the expense of truly articulating what the measure is,” Bryan said.

The bill would also require paid signature gatherers to register with the California Secretary of State and disclose the ballot measure petitions they intend to present to voters, proponents said.

Each signature gatherer would receive a unique identification number that would be included on their individual petitions. The bill would make them wear a badge displaying their number, name and photograph, making it easier for voters to identify those who misrepresent petitions.

The secretary of state would also administer a mandatory training program for paid signature gatherers that includes education on prohibited activities.

“Dissatisfaction with paid signature gatherers is as old as direct democracy itself,” said Thad Kousser, a professor political science at UC San Diego.

Kousser said states have tried to ban and regulate paid signature gatherers since as early as 1913, but the courts have protected the process. He referenced a 1988 U.S. Supreme Court decision that found the circulation of petitions to be “core political speech” and called paid signature gathering “the most effective, fundamental, and perhaps economical means of achieving direct, one-on-one communication with voters.”

Many states have added their own regulations to the process, such as California allowing people to ask if a signature gatherer is paid. He said he hasn’t seen states try to mandate that volunteers collect a portion of signatures.

Another common complaint is that signature gatherers misrepresent the groups funding campaigns. To offset those concerns, the legislation would require the petition to disclose the top three contributors to the campaign on the first page along with the attorney general’s title and summary of the measure. Signers would be required to initial a statement that says they reviewed the top funders.

Proponents anticipate opposition from oil companies and other monied business interests at the state Capitol. Though the legislation would alter the referendum process, they say the proposal would not need to go before voters because it does not change the state Constitution.

“We’re going to have pretty large opposition, but I’m hopeful that the Legislature will agree with us that it’s time to take our democracy back,” said Tia Orr, executive director of SEIU California.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.