SAN DIEGO — Twice a week, Olga Ponomareva dresses in some of her nicest clothing to stand on a sidewalk in La Jolla Shores with a display of pamphlets about the Bible.

Most of the pamphlets are in Russian or Ukrainian. Ponomareva smiles and waits. She does not approach anyone but welcomes conversations from passersby.

For the record:

3:25 p.m. Jan. 9, 2023An earlier version of this article stated that Olga Ponomareva and her mother, along with a pro bono attorney, were to present their asylum claims at a hearing that was scheduled for Friday. The hearing was Thursday.

For Ponomareva, these moments are both an expression of her faith and of her freedom. They are also a complete contrast to the restrictions that she experienced as a Jehovah’s Witness in her home country of Russia.

“What brings me the most joy is that I can simply talk to people about my God Jehovah and not be afraid,” Ponomareva said through a Russian interpreter.

The Russian government has targeted Jehovah’s Witnesses, a Christian denomination, calling them extremists and sentencing many to years in prison for practicing their religion.

Ponomareva, 48, and her friend Anna Ermak, 40, were among those charged with extremism there for the simple act of talking about the Bible with someone who had asked to study with them.

The two fled the country while their criminal cases were still in progress. They were sentenced to prison terms in absentia — Ponomareva to five years and Ermak to four years and six months — according to documents in their asylum cases.

The women and their families were among the many Russian asylum seekers who crossed the San Diego-Tijuana border by automobile in 2022 in search of protection.

Now, they are all are living together in a house in Escondido, waiting to find out whether the United States will grant them asylum.

Their cases appear strong — Russia’s persecution based on their religious practices is well documented in both news articles and court records. But, because of inconsistencies in the U.S. asylum system, it’s unclear whether they will be granted protection until they reach the end of their immigration court proceedings.

“There is always a thought of ‘what if’ — what if we will be deported,” Ponomareva said. “Especially having had prior experience of going to the courts in Russia, now that we go to court here, it just brings back those memories.”

Ponomareva and her mother will probably be the first to find out what an immigration judge will rule in their case. The hearing where they, along with a pro bono attorney, were to present their asylum claims was scheduled for Thursday. .

Persecuted for their faith

When Ponomareva was a teenager, she went to visit her aunt in Uzbekistan and was introduced to the beliefs of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The faith, which is followed by nearly 8.7 million people worldwide, is based on the Bible and recognizes Jesus Christ as the son of God but rejects the Holy Trinity doctrine, according to the group’s website. Jehovah’s Witness worship focuses on prayer, reading and studying the Bible, and sharing beliefs with others. Its doctrine is directed by a governing body of elders headquartered in New York.

Over the next several years, Ponomareva attended conventions, Bible studies and religious services with Jehovah’s Witnesses before deciding to be baptized.

“Faith in Jehovah helped me to find the meaning of life, helped me to find real friends and cope with difficulties in life,” she wrote in her asylum application.

Through the 1990s, her participation in volunteer ministry grew. She went door to door to share information about her beliefs and taught Bible studies.

Meanwhile, Ermak was introduced to the religion through her landlord when she was about 20.

Ponomareva and her mother, Ekaterina Ponomareva, now 72, moved to the small town where Ermak lived around 2016. The two met at the local Kingdom Hall, the name of the place of worship for Jehovah’s Witnesses, and became friends. They had no idea how closely their lives would come to be linked.

In 2017, Russia banned Jehovah’s Witnesses from practicing yheir faith. While Russia recognizes Christianity as one of the country’s “traditional” religions, it places special importance on the Russian Orthodox Church.

Since then, according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, more than 600 Jehovah’s Witnesses have been charged with “organizing the activities of an extremist organization.” Nearly 350 have been detained or arrested, and about 100 were being held in prisons as of October 2022.

According to a U.S. State Department report from 2021, the Russian government has targeted some other religious groups, as well.

Since they were no longer allowed to worship in their Kingdom Halls, Jehovah’s Witnesses began meeting in small groups in homes until that, too, became unsafe. Then they began meeting on Zoom in 2019.

“We had to take extreme precautions out of fear that our neighbors might report our worship to the police,” Ponomareva wrote in her asylum application. “While attending congregation meetings over Zoom, we closed all of the windows in our house and sang songs to Jehovah very quietly to avoid detection.”

That year, Ponomareva had an operation on her liver due to a chronic condition. Though her religion does not permit blood transfusions and she repeatedly informed the government doctors that she refused to receive that kind of treatment, she said they forced her to have it anyway.

“I have persisting feelings of emotional pain from that violation of my body and conscience,” Ponomareva wrote. “Theoretically, I could sue the doctors or report them to the police, but in reality the police would not defend me. On the contrary they would only persecute me for my faith.”

In 2020, Russian federal security police, known as the FSB, recruited a woman who had appeared to show interest in learning about the Bible from Ponomareva and Ermak, according to Ermak’s asylum application. The woman secretly recorded their study sessions and gave the recordings to the police.

In 2021, the FSB searched both women’s homes, and Russian authorities filed criminal charges against Ponomareva and Ermak. They attended the first few hearings and then decided to flee.

Escaping to the U.S.

First, the two women, along with Ermak’s children Mikhail, now 13, and Konstantin, now 2, tried to fly out of Russia, but they were stopped at the airport and told that they could not leave the country, they said.

Mikhail returned home, but the two women and baby Konstantin made their way to the border with Belarus, where they were able to cross and take a flight to Georgia, a country that does not require visas for Russian travelers.

To avoid leaving a paper trail, the women paid cash for the trip. Ermak recalled wearing a cap and facemask so that she would not be recognized. The two women could not eat for several days, but Ermak was still breastfeeding Konstantin.

When they arrived in Georgia, fellow Jehovah’s Witnesses helped them find a place to stay. They even received financial support from a Jehovah’s Witness in Germany.

But they did not yet feel safe.

“We were constantly afraid,” Ermak said. “We were afraid of being followed or being watched inside our apartment or our place.”

Ponomareva recalled her friend describing the experience as like a movie that should’ve been about someone else.

Slowly, they were able to organize for their remaining family members to join them in Georgia. First came Mikhail, then Ponomareva’s mother and finally Ermak’s husband, Maxim Ermak, 46. To be truly safe, they decided to head to the United States.

They learned from websites about the path that many Russian asylum seekers take through Mexico, from Cancun to Tijuana. Mexican immigration officers look for people who appear to be heading to the United States and stop them from advancing, so the websites teach asylum seekers to blend in with tourists going on vacation.

The two families arrived in Cancun in the spring of 2022. They spent almost a week there before moving on to Tijuana.

At the Tijuana airport, immigration officials stopped and questioned them. The families had to show that they had tickets on return flights to Russia before they could continue. They had purchased those flights, hoping they would never be used.

Outside the Tijuana airport, a fellow Jehovah’s Witness was waiting for them and helped them find a place to stay. They spent a couple of weeks in quarantine in Rosarito after getting sick with COVID-19.

After they recovered, they tried twice to go on foot to the U.S. via ports of entry, but both times they were turned away by Customs and Border Protection officers.

“We had explained that we were persecuted, but the officer told us there is Title 42 in place and did not allow us to go through the border,” Ponomareva said.

Title 42 is a policy put in place at the beginning of the pandemic that blocks asylum seekers and other undocumented migrants from crossing onto U.S. soil and expels them to Mexico, ostensibly to stop the spread of COVID-19. Whether and how long it will continue is currently dependent on a set of court cases that are growing more complex.

The two families decided to try crossing in a car — a strategy used by many Russian asylum seekers to get onto U.S. soil before they are turned away. Though Title 42 in theory applies to everyone, in practice it mostly affects the nationalities that Mexico is willing to accept, which does not include Russians. That means that if they can get onto U.S. soil, they can invoke their right to asylum screenings.

It took two tries for the families to reach U.S. soil, crossing through the Otay Mesa Port of Entry in June.

They were taken into custody and transported to holding cells at the San Ysidro Port of Entry. Ponomareva and her mother were released that same day to a shelter in San Diego that places arriving asylum seekers in hotel rooms until they can travel on to their final destinations around the United States. The Ermaks were released the following day.

“Once we crossed the border, it was the very first time for a long period that I finally felt that I am safe,” Ponomareva recalled.

Finding home in San Diego

Because of coronavirus precautions, the two families were not able to visit each other in the hotel. It was the most time they had spent apart since their escape from Russia.

A friend in San Diego arranged for them to stay with fellow Jehovah’s Witnesses locally, and then they found a home to rent together.

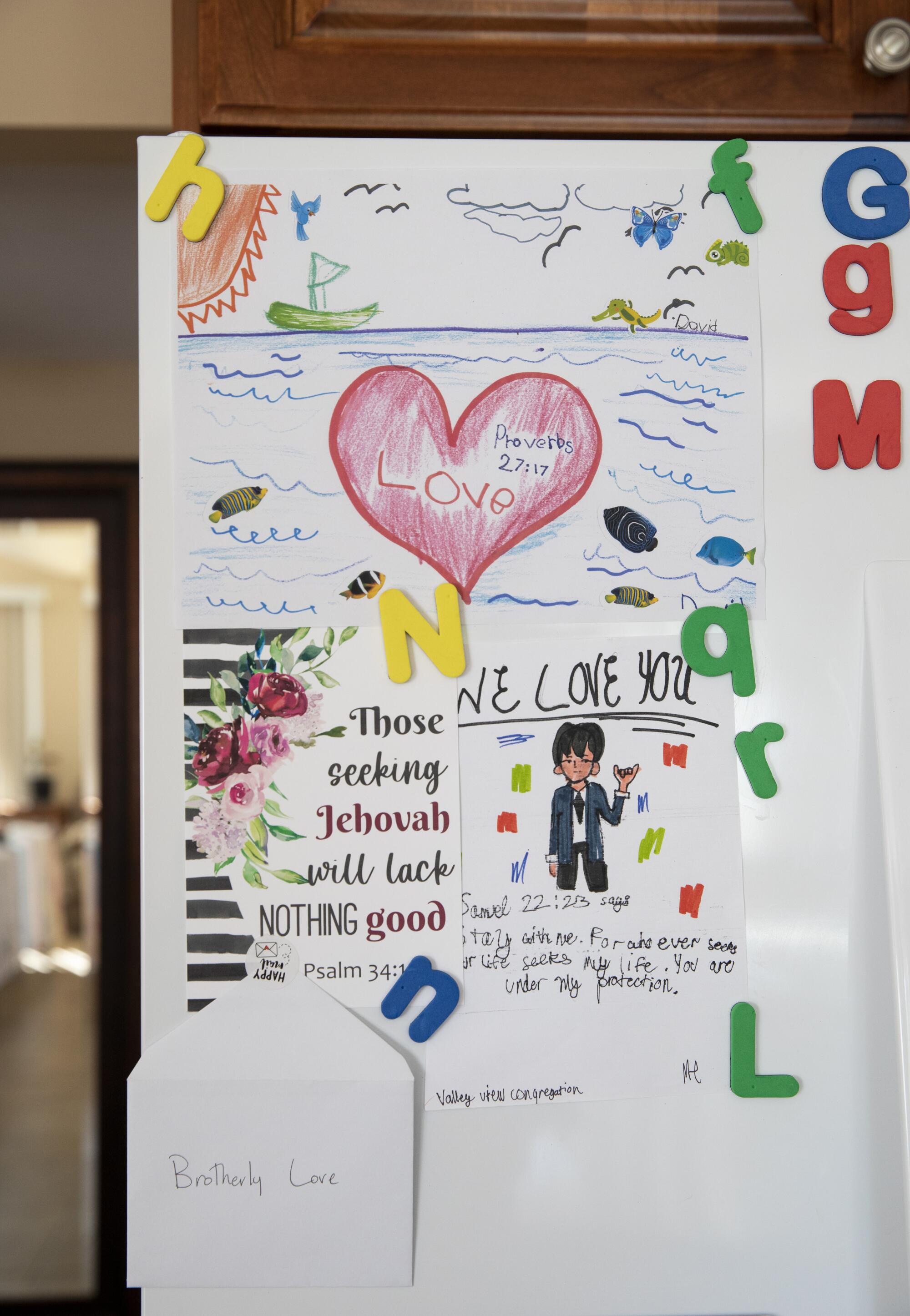

They continue to be supported by the community of Jehovah’s Witnesses in San Diego County — including Russian-speaking congregations in Encinitas and La Mesa. On their refrigerator are notes and drawings from new friends who have dropped off food. Tucked into a corner of their living room are moving boxes filled with donated toys collected for Konstantin.

Ermak’s husband, who was once a professional soccer player, has made new connections through the sport. Mikhail also loves soccer and has found acceptance in school through his skills.

Ermak walks often with Konstantin to a nearby park, and on their days off, the whole family goes with them.

Slowly they have begun to heal from the trauma of their persecution.

“The first couple of days when we just moved I was still feeling as if I am under surveillance,” Ermak said. “I had the feelings that there must be a camera somewhere hidden, someone is watching me, but I don’t have those feelings anymore. I feel safe now.”

In her asylum application, Ermak recalled the home her family had in Russia, the garden and trees they had planted. She lamented that they would not get to see how the trees grow. They also had an apartment that they intended to give to their older son.

“It wasn’t easy for us to leave what we had, and start over with nothing. But for the sake of safety and to continue worshiping Jehovah, we did it,” Ermak wrote. “The idea of giving up worshiping Jehovah never occurred to me. That would be betrayal on my part.”

Ponomareva taught English to children in Russia, and she is working to improve her language skills. Her mother and Ermak are also taking English classes.

On a recent Tuesday, a woman from Belarus stopped her stroll along the beach to talk with Ponomareva while she stood by her display. The woman, who has lived in the U.S. for decades, was excited to speak her native language with someone.

Sometimes no one talks to Ponomareva when she does her ministry. Sometimes Russian speakers like the woman from Belarus pause to chat. And sometimes people have questions about her faith as a Jehovah’s Witness.

The point, Ponomareva said, is that she makes herself available, and people know where they can find Jehovah’s Witnesses if they want to connect.

For Maxim Ermak, who often fills in the gaps of his limited English with gestures and a mobile phone translation app, his family’s new life in the United States represents something that they could have never had in Russia.

“Basically, it is freedom,” Ermak said in English.

His accompanying gestures emphasized the fullness of his gratitude.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.