New push to force California lawyers to report misconduct by fellow attorneys

An influential Sacramento lawmaker has proposed legislation that would require California’s 266,000 lawyers to report misconduct by colleagues to the State Bar, the agency that regulates the legal profession.

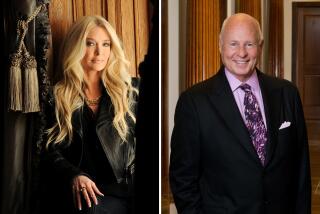

The bill introduced this week by state Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Orange) comes after a Times story noting that California is the only state that does not require or encourage lawyers to turn in their peers for wrongdoing and that highlighted how that outlier status may have figured into the corruption by Los Angeles legal legend Tom Girardi.

Umberg, a practicing attorney who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, said in an interview that the Girardi scandal had exposed numerous shortcomings in the legal system.

“One flaw is that unlike the other 49 states, California imposes no duty on a lawyer to expose egregious misconduct or even in this case, potential theft of funds that rightfully belonged to victims. And so that needs to be addressed,” Umberg said.

The proposed legislation requires a lawyer licensed in California “who knows that another licensee has engaged in professional misconduct” to notify the State Bar if the violation “raises a substantial question as to that licensee’s honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness as an attorney in other respects.”

The bill exempts attorneys from disclosing information to the agency that is protected by attorney-client privilege or was obtained in a Bar-sponsored program for attorneys with substance abuse or mental health problems.

After the bill was proposed Monday, the chair of the State Bar’s board of trustees announced his support for the legislation.

“The public we all are mandated to protect will be the ultimate beneficiaries of these proactive actions,” Ruben Duran said in a statement.

Girardi, a nationally renowned trial attorney, maintained a prominent and powerful place in Golden State law despite scores of accusations in court cases that he misappropriated settlement money and cheated fellow attorneys out of fees. After his firm collapsed two years ago, many in the L.A. legal community said Girardi’s thieving was something of an open secret.

In The Times’ report published in October, a former attorney at his firm, Girardi Keese, said he left the firm two years before its fall because Girardi had stolen millions from one of their clients, a burn victim, and his family.

Attorney Robert Finnerty told the newspaper that at the time he researched whether he had a legal duty to report Girardi’s misappropriation to the State Bar.

“I was surprised we didn’t have one,” said Finnerty, who did not notify authorities, but worked to file a lawsuit against Girardi and ultimately secured a judgment for the burn victim’s family.

California’s legal community, the largest in the country, has resisted mandatory reporting since the 1980s when other states began adopting versions of a model rule drawn up by the American Bar Assn. The disdain for it is so pronounced that many California lawyers have borrowed from gangster jargon to call it the “snitch rule” or “rat rule.”

Some attorneys have said the rule would be used by courtroom opponents seeking a tactical advantage, rather than by those blowing the whistle on serious corruption. Umberg said he anticipated his bill would be refined during the legislative process but that he wanted to target “the most egregious acts of misconduct.”

“Our challenge is to make sure it is not structured in such a way that, for example — someone who is being obnoxious during a deposition — is something that the [State Bar] would get involved in,” Umberg said.

Carol Langford, a Bay Area attorney who frequently represents attorneys accused of misconduct, said she expected wide opposition to the bill and disputed the suggestion that it could have stopped Girardi.

He was the subject of more than 200 complaints to the State Bar over the decades yet was never publicly disciplined.

“You can put [a mandatory reporting requirement] on the books, but that’s not what the problem was. Internal corruption of a government agency — that’s what the problem was,” said Langford, who also teaches ethics at the University of San Francisco School of Law.

Langford said that if attorneys see misconduct by another attorney on a case, they have a duty to tell their client about it since it is a significant development in the case. She said it should be up to clients to decide whether they want it to be reported to the Bar.

“Your primary obligation is to not anyone but your client,” she said. “Sometimes it doesn’t behoove the client to have the Bar know, and not because you are helping them commit a crime, but it could be embarrassing or detrimental.”

The State Bar’s chief prosecutor, George Cardona, who was appointed last year to reform the agency’s discipline system, had opposed the law in 2015 while he was a federal prosecutor serving on a statewide commission to improve professional ethics. But Cardona told The Times this fall he had changed his position after seeing firsthand the damage Girardi had inflicted on the legal establishment.

The agency’s executive director, Leah Wilson, acknowledged recently that much of the legal establishment opposes the requirement as “more for optics than for impact.”

But, Wilson added, “We aren’t in a position to know that because we’re the only state in the country without a similar rule. And I think that’s just not viable for us any longer.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.