L.A. teachers union seeks 20% raise, saying educators are stressed out and priced out

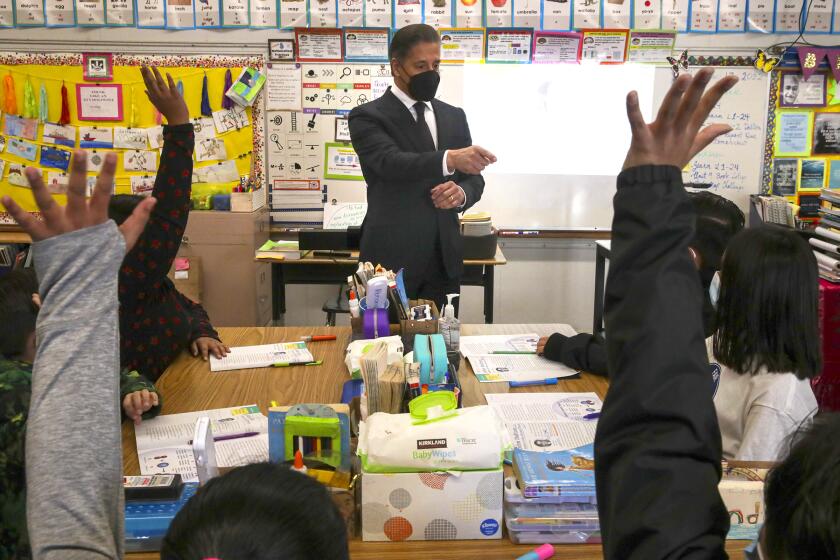

The Los Angeles teachers union is pressing its demands for a 20% raise over two years, smaller class sizes and a steep reduction in standardized testing — the latest stress test for the nation’s second-largest school district and Supt. Alberto Carvalho as the system struggles to address students’ deep learning setbacks and mental health needs in the wake of the pandemic.

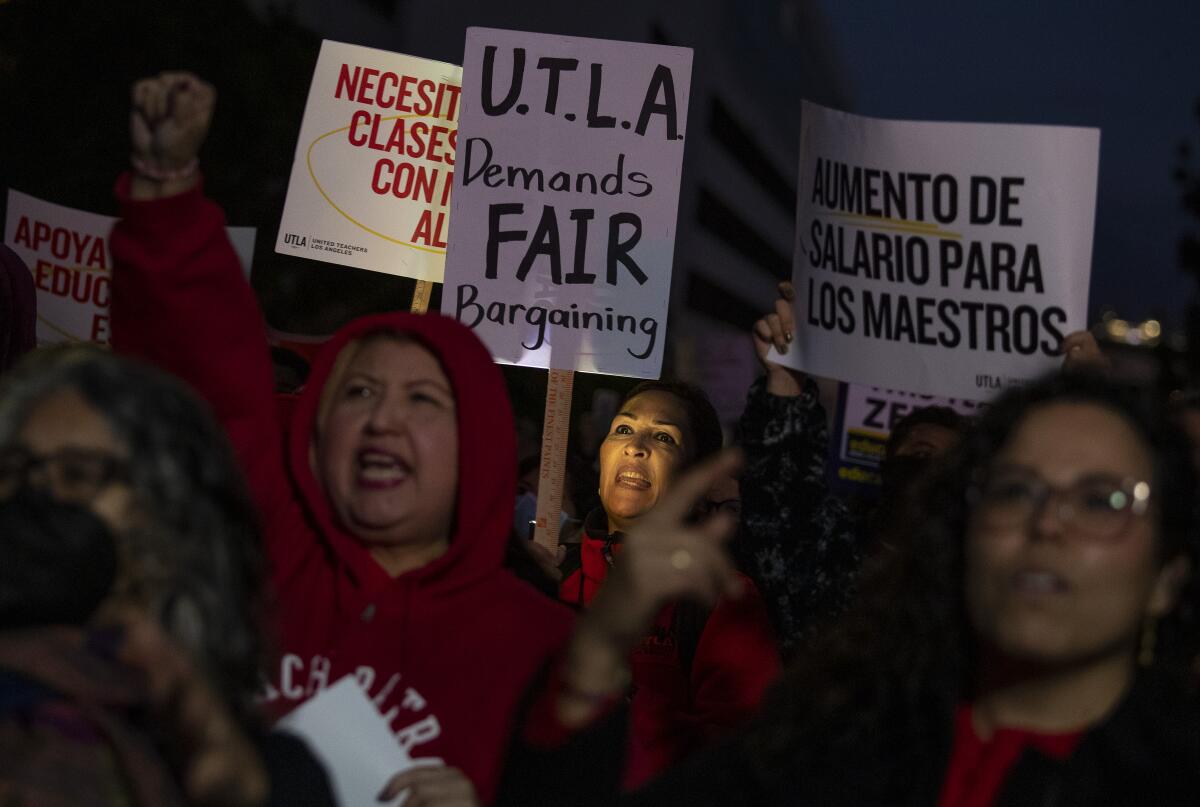

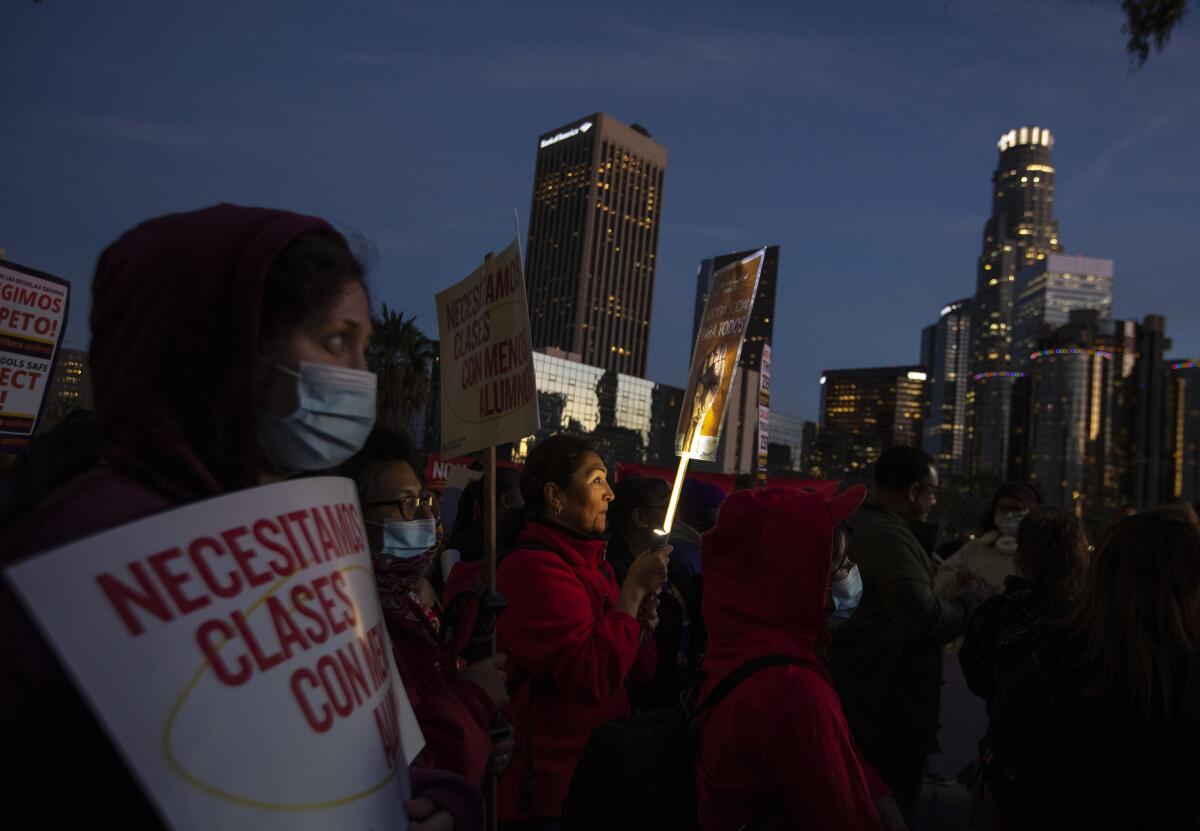

For United Teachers Los Angeles — which staged three simultaneous rallies Monday across the vast school system — its contract platform speaks to the intense pressures that members say are pummeling their profession, leading to dire teacher shortages in California and throughout the nation. Ongoing economic uncertainties and the high costs of living and housing in Los Angeles have intensified their focus on contract talks as teachers worry about career sustainability and increasing workloads.

“When you can’t even afford to live when you work, we got a problem y’all,” UTLA President Cecily Myart-Cruz said in impassioned remarks that closed the rally outside district headquarters just west of downtown. “This district has had seven whole months to address the educator shortage and to make sure that every student has a classroom teacher, every student has a school nurse, every student has a counselor and a librarian and mental health support.”

A first-year teacher earns a base salary starting at $48,916. The base salary for a teacher with 10 years of experience is $61,557.

However, teachers can earn more based on other skills and levels of education. A 10-year teacher, for example, can earn as much as $98,176, with salary credits, including increases for a doctorate degree, bilingual skills and completion of professional development courses.

Neither the union nor the district could immediately provide the average or median teacher salary.

Speakers at the rally included newly elected school board member Rocio Rivas, who benefited from a multimillion-dollar independent campaign on her behalf from the teachers union.

While Myart-Cruz sought to fire up rank-and-file union members, school district officials sought to tamp things down.

“Los Angeles Unified continues to meet with our labor partners regularly,” according to a statement the district issued in the afternoon. “We respect and acknowledge the dedication of our employees and the need to compensate them fairly in this current economic environment. We remain dedicated to avoiding protracted negotiations to keep the focus on our students and student achievement.”

At the rallies, participants focused on record multibillion-dollar reserves, with the message that if teachers and other employees can’t be rewarded and helped now, then when would it ever be possible?

Carvalho, in turn, has focused attention on potential difficulties ahead. Financial forecasters, including the state legislative analyst, warn of an economic downturn just as one-time COVID-19 relief aid is winding down. A raise that is affordable in 2022 must still be paid for three years from now — when money is likely to be tighter, and when steadily declining student enrollment could create more financial pressures.

At Tuesday’s board meeting, Carvalho said it would be irresponsible and unfair to students and employees to authorize a raise that the district could afford today only to have to lay off employees and disrupt education in the years to come.

There’s money for Supt. Alberto Carvalho’s ambitious agenda, but much of it is one-time support and declining enrollment will affect ongoing funding

The L.A. Unified labor actions come as a massive strike among UC academic workers enters its fourth week, with 48,000 teaching assistants, tutors, graduate student researchers and postdoctoral scholars also decrying the high cost of California housing in their demand for a significant pay increase, along with more support for child care, healthcare and transportation. The workers have rallied on campuses throughout the state for several weeks and held sit-ins on Monday, with sides far apart on money.

A common theme for both unions has been the high cost of living in the region, which teachers brought up repeatedly at the downtown union rally.

“As someone who’s new to L.A., teachers do not make enough money to live in the city at all,” said Nekhoe Hogan, a third-year teacher at Manual Arts High School, south of downtown. “The public needs to recognize that teachers are asking for basic necessities, and then to have working conditions be normal — not too many kids in the classroom, not too many administrative things to take care of that prevents them from actually doing their job just teaching kids.”

Other factors also are making the job challenging, including working with students who are behind academically and have greater emotional needs because of pandemic hardships.

“There are many things that they should know currently that they don’t know,” Hogan said. “And so I feel a sort of responsibility to make up two years of education within a semester essentially — and that’s impossible.”

The annual income needed to buy a home in Los Angeles is more than $220,000, a recent study found, with higher mortgage rates and inflation cutting deeper into household incomes. The median annual household income in 2020 in L.A. was just over $65,000.

The union put forward an analysis that L.A. Unified “is in the bottom quartile of L.A. County school districts when it comes to teacher compensation.”

L.A. teachers union members also have health benefits that are considered high quality at comparatively low cost.

The rallies included parent supporters. Some other parent leaders, who did not attend, are concerned about labor strife leading to more potential learning disruptions. The previous contract settlement was reached only after a one-week strike in January 2019.

Families “are tired of the politics and endless chaos,” said Christie Pesicka, a spokesperson for a parents group that has been critical of the teachers union. “Enrollment is plummeting. By the time the bickering settles, there may not be enough students left for LAUSD to remain solvent.”

Negotiations with United Teachers Los Angeles are relatively distinct. Beyond seeking a pay increase, the union is pushing for changes in the way students are schooled in their “Beyond Recovery” platform, which aims to “ensure our neighborhood public schools meet the unique needs of students, families and educators in each community.”

Saying that standardized assessments take valuable time from learning, the union is calling for elimination or dramatic reduction of such tests when they are not required by the state or federal government.

Carvalho has acknowledged that such assessments are not always well organized or consistent from one region of the district to another, but has defended their intent. The tests are used as fundamental measures to guide instruction across the system, especially under the data-oriented Carvalho.

The alarming dip in math proficiency and smaller declines in English in the last two pandemic-disrupted school years hit students who were already behind.

Some of what the union frames as demands are in line with district goals, such as expanded access to dual-language programs and more ethnic studies classes. Like the union, the district supports putting a full-time nurse in every school, but hasn’t been able to hire them in a competitive job market.

The union wants a class-size reduction of four students everywhere over the next two years. The district wants to target reductions to where it’s needed most — based on academic performance and the percentage of low-income families.

Some critics view many union proposals off topic or the prerogative of management. But even with the bread-and-butter agenda, UTLA is known for pushing hard compared with teacher unions elsewhere — and such is the case with the 20% wage proposal.

The district is so far offering 8%, according to bargaining updates that the union posts online.

UTLA leaders take pride in having a curricular and social agenda — the union’s platform calls for installing solar panels and buying electric buses.

The union package also calls for a freeze on school closures — which are increasingly hard to avoid as enrollment shrinks — and an end to “the over-policing and criminalization of students in schools.”

The platform does not explicitly call for the end of school police, although union leadership supports its elimination. A union proposal submitted earlier this year sought to “end all requirements for the engagement of police except where mandated by federal, state or local law requiring the involvement of police.”

The union bargaining platform also calls for the district to “push for” federal “housing vouchers to support LAUSD families” and to “convert vacant LAUSD property into housing for low-income families” — although it’s challenging to see how these elements would be enforced through a teachers contract.

Other L.A. Unified bargaining units have typically benefited from UTLA’s hard line — as their raises and benefits have come to mirror those fought for by UTLA. Another union, however, is independently assertive, Local 99 of Service Employees International Union, which represents the largest number of nonteaching employees, including bus drivers, teacher aides, custodians and cafeteria workers.

Local 99 members include some of the lowest wage earners in the school system — earning $25,000 a year on average for work that is frequently part time. They’ve scheduled their own rally for next week.

In the big picture, 2022 has been a year of relative labor calm for K-12 education in California.

“Record funding — so many districts are settling early and working collaboratively with employees to improve programs, et cetera,” said Frank Wells, a regional spokesman for the California Teachers Assn. “Others for whatever reason are taking an unnecessarily hard-line approach.”

In particular, Wells was talking about Covina-Valley Unified, where teachers came within hours of going on strike last week. That strike was averted with a tentative agreement. In Glendale, the teachers union and school district are in mediation.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.