More than 1,000 UC faculty members urge Newsom, lawmakers to support striking academic workers

More than 1,000 University of California faculty members are imploring Gov. Gavin Newsom and state legislators to wade into the ongoing academic workers strike and urge UC leaders to meet union demands.

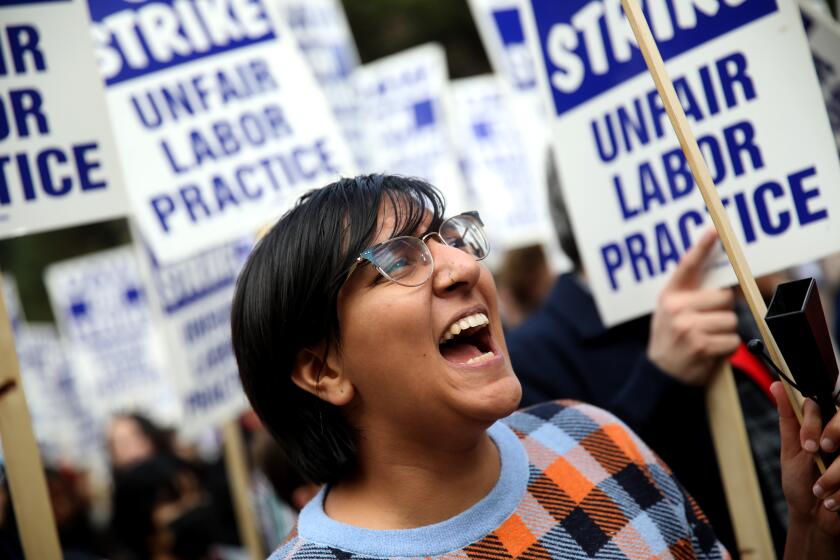

In a letter signed by faculty from all 10 UC campuses, and during a rally Friday afternoon at UCLA, the group called on Newsom to push university leaders to bargain “in good faith” with the United Auto Workers, the union representing the 36,000 teaching assistants, tutors, graduate student researchers and postdoctoral scholars who have not reached an agreement with the system.

With the strike entering its fourth week Monday — after class cancellations, scaled-down finals and anxiety over semester grading — the letter represents the strongest public support yet from faculty members for striking graduate students, teaching assistants and tutors. These workers lead course discussions, run labs, grade assignments, administer exams, conduct research and perform other roles.

The union is demanding significant pay increases to help workers afford housing in the high-cost areas where most UC campuses are located, along with more support for child care, healthcare, transportation and international students. The employees said the system’s current wages and benefits are “unlivable” and harmful to their mental health and capacity for teaching and conducting research.

UC’s offers are not close to the demands on key salary issues, but university officials have said they have been “fair, reasonable and responsive to the union’s priorities.”

The faculty want Newsom and lawmakers to “reinvest in” California’s “flagship education institution” and draw from state coffers to pay for wage increases and other benefits.

A spokesperson for the Newsom administration did not comment on the details of negotiations with UC leadership but pointed to a preexisting commitment by the state to boost funding for higher education.

As 48,000 University of California academic workers push their historic strike into a third week just days before finals, tensions and anxiety are rising. “People are losing their minds,” a UC Santa Barbara professor says.

Last year’s state budget included 5% increases in base funding for UC over five years in exchange for “clear commitments” from school administration regarding access, affordability and other goals. The state has a similar agreement with the California State University and community college systems.

“The state’s commitment to ongoing predictable increases in base budget funding predates this recent action by some of the faculty groups,” H.D. Palmer, spokesperson for the state Department of Finance, said Friday. “At a time when we are looking to close a budget gap that is estimated to be $25 billion, that’s a funding commitment for increased support for UC that doesn’t exist in virtually any other aspect of the budget.”

Newsom is expected to release his budget proposal for the 2023-24 fiscal year in January. With a recession looming and the state facing a potential $25-billion budget deficit, the outlook for significant spending increases is unlikely.

In a statement, Ryan King, a UC spokesperson, said the system is grateful to Newsom and the Legislature for its “continued support.” The statement did not directly address faculty members’ demands that the state set aside more money for the system.

“We recognize the challenges that the strike has created for our faculty and value their continued commitment to educating and supporting our students under these circumstances,” King said. “We remain focused on working with the UAW to secure fair contracts.”

Faculty members emphasized Friday — the last day of instruction in the fall quarter — that much is at stake.

Faculty members stood on steps in the middle of the UCLA campus, opposite picketing workers, holding a banner that read, “We stand with our students.”

Anna Markowitz, an assistant professor of education, said graduate students are essential to her work and to the experience of undergraduate students. She has felt guilty for recruiting graduate students knowing that they would struggle financially.

“Since I got here, I was aware that they were being paid a poverty wage and that the work I asked them to do was not earning them a wage that earned them enough to live securely,” she said.

Markowitz said she will not submit her students’ grades for this quarter until the strike is over. Doing so would not hurt students, she said, and sends a message to UC that “we’re not going to continue with business as usual.”

Graeme Blair, an associate professor of political science at UCLA, said teaching assistants and postdoctoral researchers work long hours, well beyond what UC administrators say they do.

“One of the most poisonous arguments the UC has made is that student workers are only working half time. That’s a misdirection,” he said. “From seeing graduate students every day ... they’re working around the clock.”

In the letter to Newsom and state lawmakers, faculty members wrote that failing to provide academic workers with higher wages and other benefits would undercut UC’s ability to attract high-caliber scholars.

“Neither the existing UC wages, nor the current proposed increase, are competitive with peer institutions, threatening UC’s ability to bring in the best and brightest, and undermining its contributions to Californians,” the letter said, highlighting research showing that funding for the university system’s graduate student workers lags behind that of other schools.

In 2019, a group of UC administrators and doctoral candidates acknowledged the need to bolster financial assistance for graduate employees and provide more support as they navigate “enormous challenges in finding affordable housing.”

The strike of 48,000 University of California workers may have long-lasting consequences to the system’s teaching and research excellence, some fear.

Two of the bargaining units representing postdoctoral scholars and researchers this week reached a tentative agreement with UC, but workers in those units have not returned to campus in solidarity with the 36,000 employees who remain on strike. The postdoctoral employees and academic researchers make up about 12,000 of the 48,000 union members. They say the tentative deal will raise the minimum annual pay for their full-time positions from about $55,000 to $70,000 or higher with various adjustments by the end of the five-year contract — including a $12,000 raise by October 2023.

After the rally, academic workers and faculty members marched to a faculty building, chanting, “Get up, get down, L.A. is a union town.”

Among those on the picket line was Jacqueline Perez, a third-year doctoral student studying social psychology. Perez is expected to work full time as a student researcher on her own studies about how socioeconomic adversity affects romantic relationships and family processes.

But the 24-year-old said she had to take on an extra part-time position as a teaching assistant to afford rent and basics. She takes home about $1,900 a month from her position as a student researcher and $1,100 a month as a teaching assistant, a job that typically takes up to 20 hours a week.

“Just to know that we have people who are in positions of power who have way more leverage and authority than we do, to stand behind us ... it really means everything,” Perez said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.