Villanueva could do what decades of police reformers could not: Place limits on L.A. County sheriff

In Los Angeles County, when it comes to policing, the lines of authority have always been clear: The Board of Supervisors controls the purse strings and the sheriff handles the rest.

But after four turbulent years in which Sheriff Alex Villanueva pitted himself against the board and indignantly fought off its efforts to rein him in, that balance of power looks likely to be dramatically upended by voters.

There are many ballots left to count, but voters so far have come out overwhelmingly in favor of Measure A, an amendment to the county’s charter proposed by supervisors that would give the board the authority to fire an elected sheriff.

In an updated vote count released Thursday, 69% of people had supported the proposal. It needs only a simple majority to pass. It is unknown how many more ballots are left to be counted and when the tally will be completed.

“I always felt very strongly that you shouldn’t take away that power from the voters, but I was ready to say, ‘OK, let’s see how the voters feel about this — do they really want to give the Board of Supervisors more power?’” said Supervisor Janice Hahn, who supported putting the measure on the November ballot.

The early result, Hahn continued, “says that they spoke loud and clear that they want the Board of Supervisors to have the power to remove a sheriff who is dangerous or corrupt.”

Observers and the measure’s proponents say the vote tally signals a clear-cut rebuke of Villanueva, who for four years spurned the watchdogs appointed by the board to keep him in check.

But Villanueva won’t be sheriff forever — he’s currently trailing badly in his bid for a second term to former Long Beach police chief Robert Luna. And, if Measure A passes, whoever comes after him will take office under a new reality in which the supervisors have an undeniable new level of leverage.

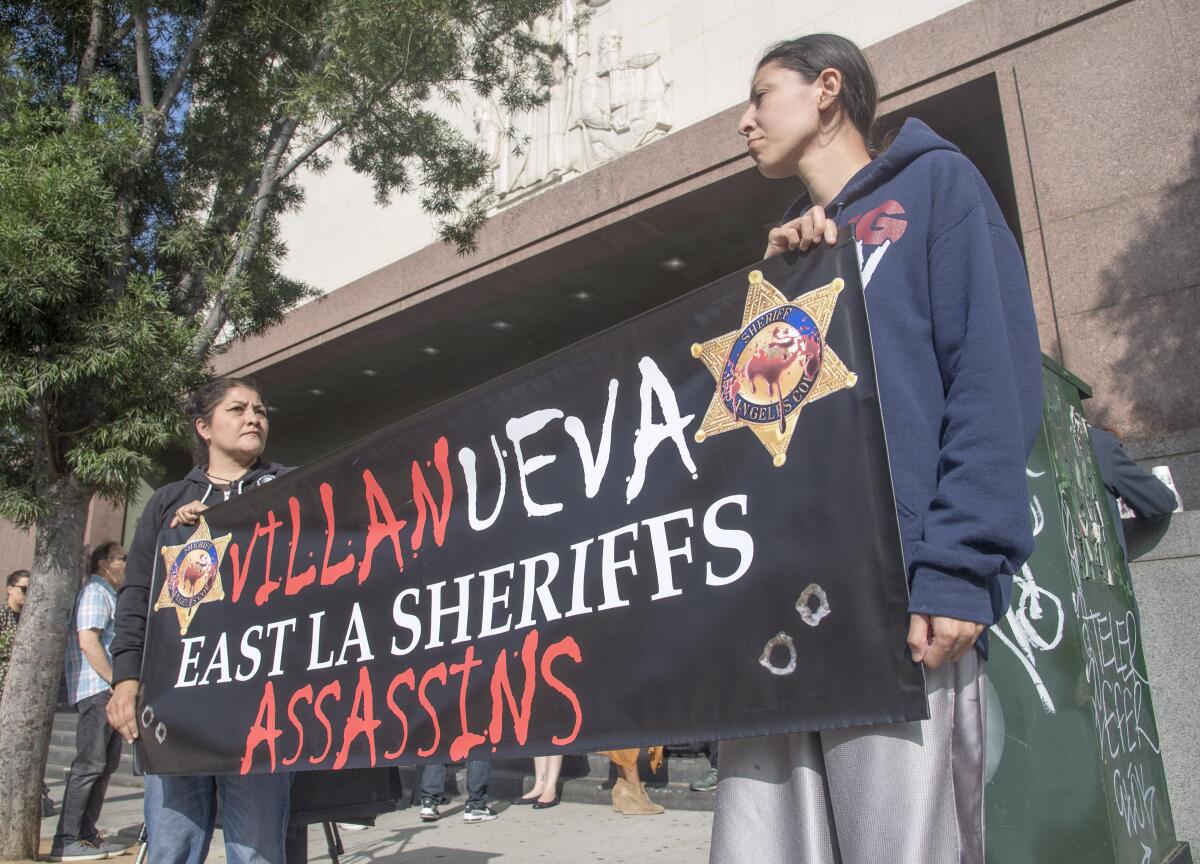

“Sheriffs prior to this law understood that they stood alone,” said Julie Diaz-Martinez, whose grandson, Paul Rea, was killed by a sheriff’s deputy in East L.A. “And that there was no accountability because they believed as elected leaders that there was no government body, no government entity that would really monitor them.”

The passage of the measure, she said, would mean that “any new sheriff understands that his job performance is under review.” She spent election day phone banking to encourage voters to support the measure.

Under the terms of the measure, at least four of the five supervisors would need to agree a sheriff should be kicked out of office. Grounds to remove the sheriff include breaking the law or other serious misconduct, such as “flagrant or repeated neglect of duties, misappropriation of funds, willful falsification of documents or obstructing an investigation.”

Supervisor Kathryn Barger, the lone member of the board who did not support putting the measure on the ballot, suggested it would be difficult to ensure the new power isn’t abused down the line, as board seats turn over and sheriffs change.

“It’s a slippery slope. I think that’s why it’s going to be important to really understand what cause exactly means,” she said. “As the board changes...I think that the lens at which they’re going to look at removal may change as well.”

For Supervisor Hilda Solis, who was reelected in the June primary to what she said would be her last four-year term on the board, having the option to remove a sheriff amounts to a good insurance policy moving forward.

“It’s kind of like in our pocket — if you don’t need to use it, it’s fine, but if we need to it’s there,” Solis said. “And I may not be there when it’s necessary.”

Before the election, Villanueva called the proposed measure a “cheap political stunt” designed to hurt his chances at a second term and suggested he’d mount a legal challenge.

He reiterated the idea Thursday in a statement provided by a department spokesperson. “Measure A appears to be unconstitutional and will likely be struck down in the courts when challenged,” Villanueva said.

Supervisor Holly Mitchell, who authored the motion to put the measure on the ballot because of “overwhelming outreach” by constituents, contended that the language was constitutionally sound.

Sheriffs before Villanueva have long held they’re accountable to voters. In 2012, during hearings called by the Los Angeles County Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, then-Sheriff Lee Baca was asked how he was to be held accountable for beatings by deputies and other problems in county jails, which are run by the sheriff.

“Don’t elect me!” Baca answered. He ultimately went to prison for obstructing a federal investigation into inmate abuses in the county jail system and lying to prosecutors about his role.

Whether the current Board of Supervisors thinks Villanueva has done something egregious enough to justify his removal will be a moot point if he loses to Luna.

If Villanueva manages a comeback win and the measure passes, the board deciding whether to use its new power will look different than the one that fought with Villanueva. Sheila Kuehl, one of the sheriff’s most ardent critics, is leaving office.

“If he’s gone, really the only point of this is if you get somebody like him again,” said Mario Mainero, an associate dean at Chapman University’s Fowler School of Law, referring to Measure A. If he is reelected, “it’s really a political decision about whether the board thinks that the kinds of things he’s done warrant” removal.

He pointed to Villanueva’s defiance of subpoenas that called on him to testify under oath about controversies in the department, as well as the widely held belief Villanueva has orchestrated criminal investigations targeting adversaries.

“Are those justifications? In my view they are, because they’re an abuse of power,” Mainero said. “Do I think they justify his removal? Personally I do.”

A Superior Court judge this week ordered the sheriff to show why he should not be held in contempt for refusing to comply with three subpoenas, while the L.A. County district attorney’s office said it has opened an investigation into whether he violated state law when he solicited campaign donations from deputies.

Zev Yaroslavsky, a former supervisor and director of the Los Angeles Initiative at UCLA‘s Luskin School of Public Affairs, said he expects supervisors would not use their newfound power casually if the measure passes. The four votes required to trigger a sheriff’s removal and requirement that a sheriff have committed serious infractions mitigated many of his concerns about the proposal.

The measure, he said, may also incentivize the sheriff not to thumb his nose at oversight.

“A political body should not remove another political person because they have a disagreement,” he said. “It really needs to be a slam dunk kind of transgression.”

For one voter at a polling center in Marina del Rey on election day, it was a no-brainer.

“Every employee gets fired for cause,” 46-year-old Sabine Pleissner said in explaining her support for Measure A. “Why would a sheriff not get fired for cause? If anything, that should be a higher standard.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.