The year was 1960 and Southern California’s most famous car salesman was going to jail.

Millions had come to know Henry J. Caruso by his ubiquitous radio and TV ads, in which the dapper dealer pitched the latest from Ford and Dodge and singers belted, “H.J. Caruso — He’s the greatest.”

Reporters called Caruso a “phenom” who at 30 already had customers flocking to his lots in Compton, North Hollywood, Pasadena and Long Beach, snapping up more than 1,000 cars a month and making him one of the nation’s largest auto dealers.

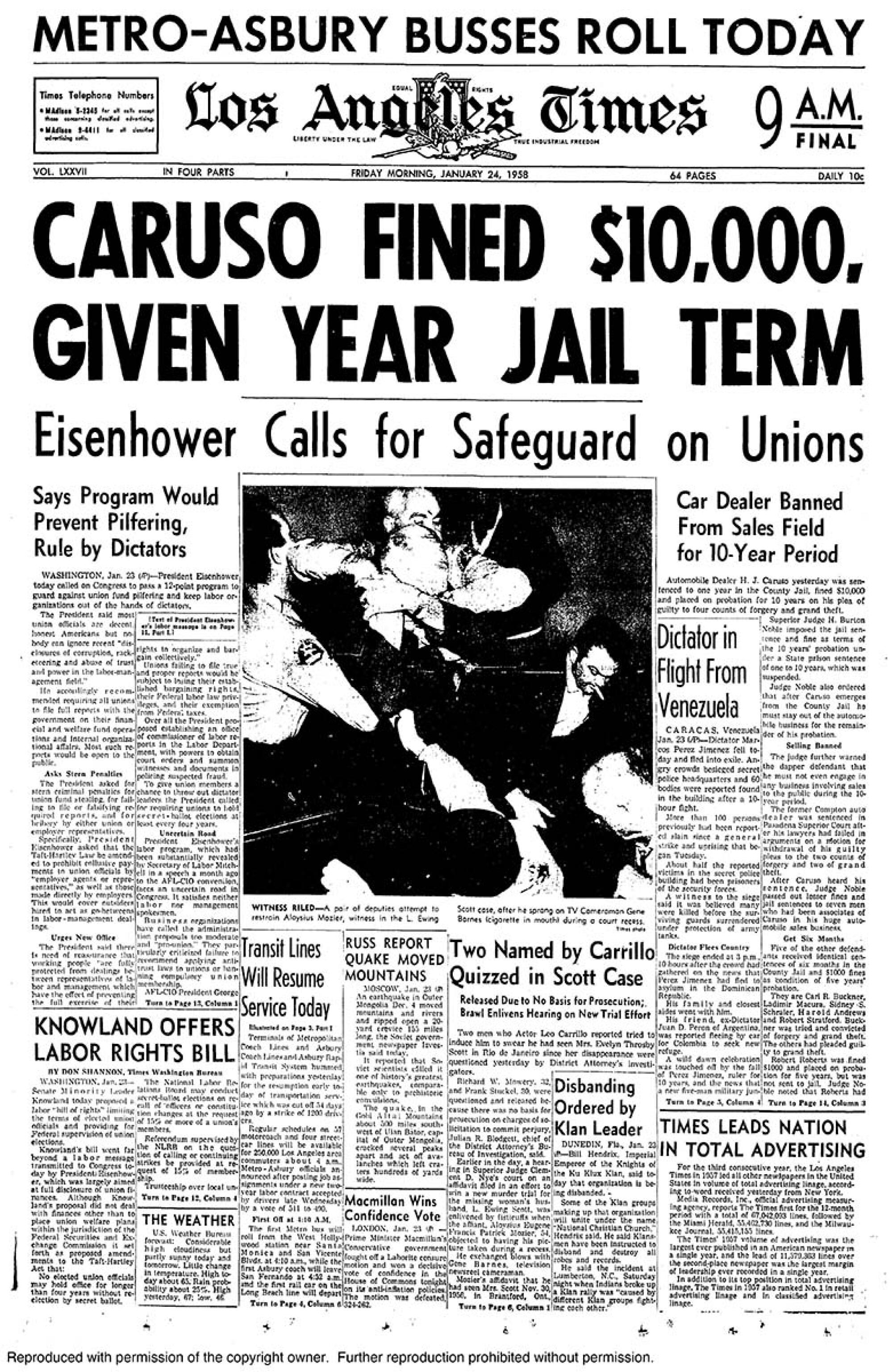

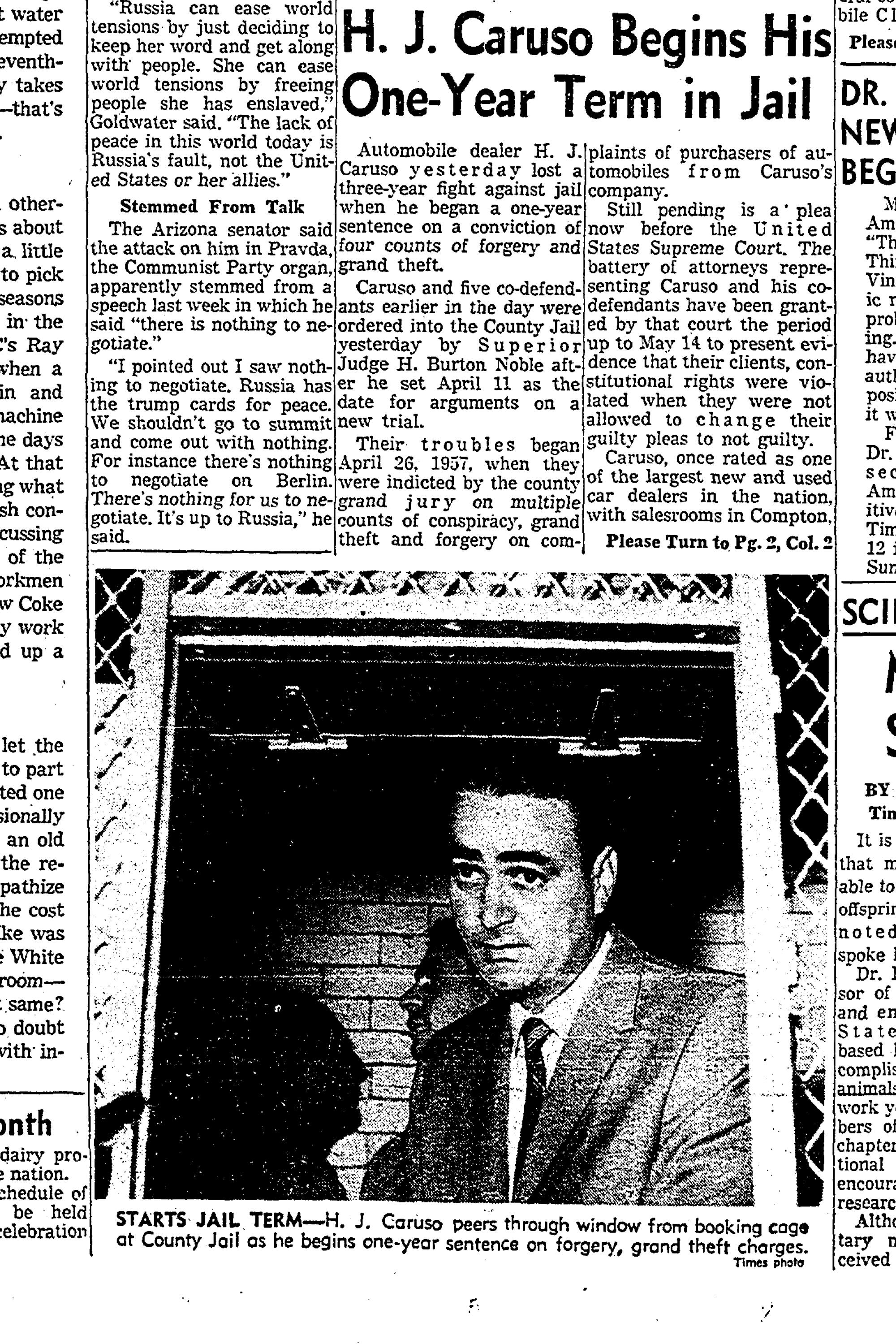

But in 1957, a Los Angeles grand jury indicted Caruso and more than a dozen of his employees, accusing them of theft and forgery.

For an empire that had generated $40 million a year in sales, the downfall was swift and humiliating.

In a Pasadena courtroom, Caruso and five former employees were sent away for up to a year in county jail. His wife, Gloria, would be raising their two children: 14-month-old son Rick and his sister.

Sixty-two years have passed, and the family’s fortunes have seen a stunning reversal — the product of bold and risky business moves along with ambition.

Now, Rick Caruso, one of L.A.’s most successful businessmen, is in the final days of his bid to be the next mayor of Los Angeles, facing off against Rep. Karen Bass in Tuesday’s election.

He has pitched a vision of L.A. that is rooted in his family’s experience here, of immigrants arriving in Boyle Heights, scraping by as laborers, and successive generations finding prosperity in quintessential Southern California industries: automobiles and shopping malls.

L.A. mayoral candidate Karen Bass combines the focus on equity from her activist days with the practicality she learned in Sacramento and Washington.

Caruso’s campaign bio notes his father “was indicted and served time for fraud,” though he, perhaps understandably, hasn’t talked much publicly about this ugly and painful chapter of his family’s life.

“He lost almost everything and was able to rebuild a business, and it became a very successful business,” Rick Caruso said in a recent interview. “What it taught me is — and I was so proud of my dad — you can come back. And you deserve a second chance.”

Veteran politicians like Tom Bradley and John Ferraro mentored Caruso, but none were more influential than his parents. In prior interviews, Caruso has said that his mother “significantly guided me in my personal and family life.” When it came to business, his dad was his top advisor, whom he would call “nearly every night to ask, ‘If you were in this position, what would you do?’”

Yet running for mayor, after coming close in 2013, meant reckoning with his late father’s opposition, rooted partly in the fear that his own past would be weaponized against his son.

Caruso outpaced his father’s wealth many times over but could never convince him politics was a worthwhile pursuit. His dad even joked to friends that if Rick ran for office, he’d donate to his opponent. Over the years, Caruso came to believe his father wanted to shield him.

“I think it was protective of me, protective of the family, probably protective of himself, not wanting his story to come out,” Caruso said, adding that his father looked at politics and said: “‘Why would you want to be a part of that?’”

Deciding to run was the culmination of an intense father-son bond that was full of love and mutual respect but also defined in part by a son’s decades-long effort to chart his own path as a businessman and civic leader.

“At one point, certainly, I think wanting to make his father proud really drove him,” said Maria Shriver, the NBC News special anchor and former first lady of California who raised her children alongside the Carusos’ and has known the family for decades. She saw a different motive today. “As he said to me, ‘I don’t want to sit back and think I didn’t try.’”

*

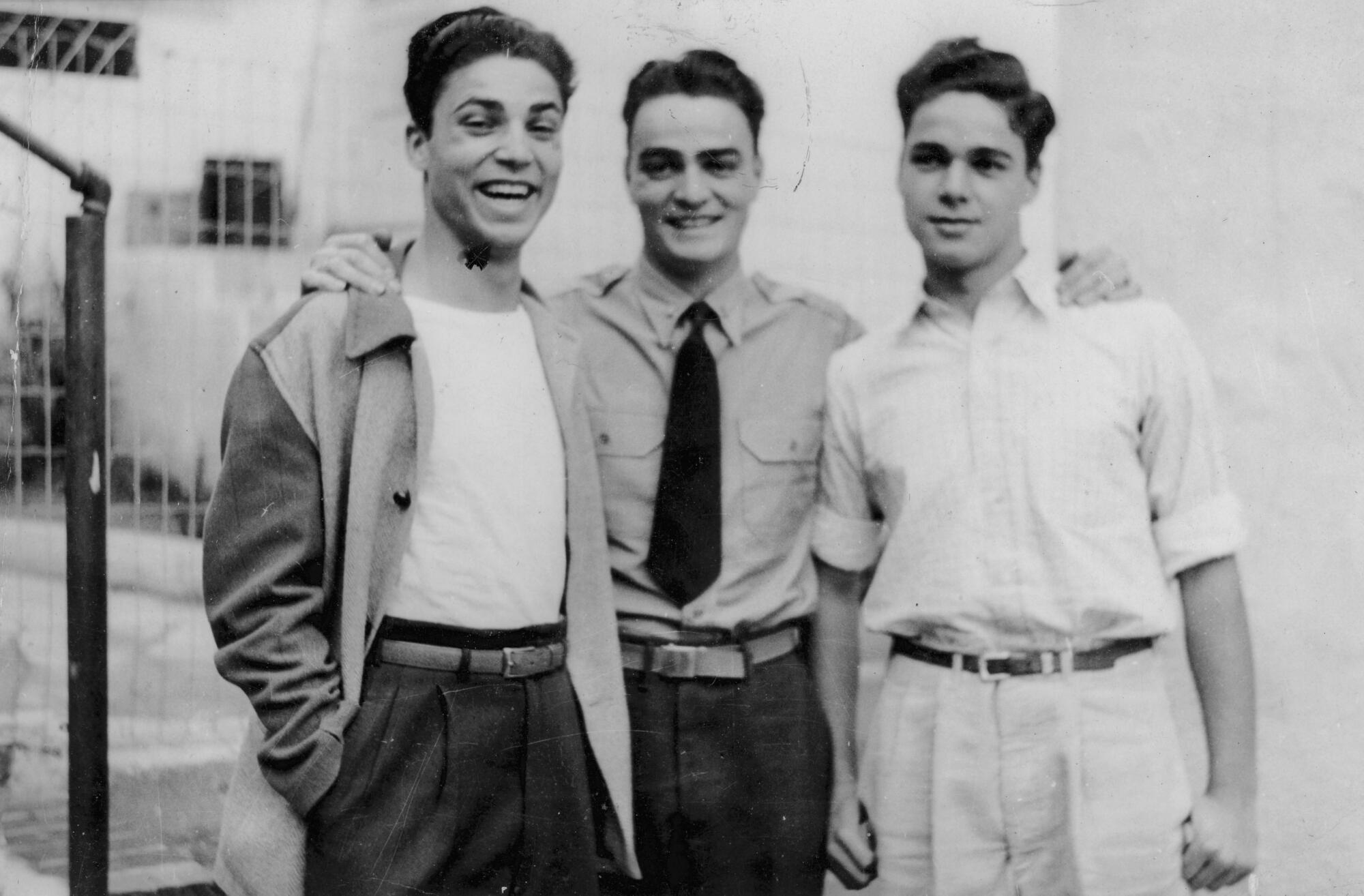

Henry Caruso was born in a coal mining town in western Pennsylvania, the eldest son of Josephine and August. Both had come through Ellis Island from towns in Calabria, near the toe of Italy, and settled in Boyle Heights with their three sons in the late 1920s.

August couldn’t read or write, but worked as a gardener, census records show. His wife worked at a bakery. And although their son Henry studied pre-med at USC, he dropped out, enlisted in the Navy and became a pilot, according to Caruso.

With money saved while in the Navy, Henry secured part-ownership in 1951 of a used-car dealership, followed by a Hudson dealership. From there, his automobile empire mushroomed, built on clever advertising and aggressive pricing.

The criminal charges came in 1957, when Hank, as he was called, and 16 employees at his car lots were indicted on charges alleging they had cheated customers by altering sales contracts or using misleading tactics. Among those indicted was Hank’s younger brother, Albert.

One customer, Jack Dover, recounted his automobile purchase at a Caruso lot in Compton, according to 60-year-old court records obtained by The Times. He testified to purchasing a car for $3,500 and initialed a blank sales agreement. The document later showed $3,700, which Dover insisted was not the agreed-upon price.

Another customer, Clare Ferguson, contended he purchased a car for $3,400 instead of the $4,400 stated on the sales contract. The automobile had been sitting under a sign advertising a $1,000 discount. When he learned the car cost $4,400, he was told it was too late to return it.

Hank thought his rivals in the auto business had a hand in his prosecution. But he pleaded guilty to the charges related to Dover, Ferguson and another customer, believing his lawyer had secured a deal that reduced his case to a misdemeanor, avoided jail and allowed him to move on. That deal never materialized.

When 11 ex-employees proceeded to trial, all but two were acquitted, including Caruso’s younger brother. After the verdict, Caruso and the others who entered guilty pleas sought to withdraw their pleas and head to trial.

Hank blamed one of his lawyers, Fred Howser, a former L.A. County district attorney and state attorney general, who negotiated the plea and said it had to be accepted as soon as possible.

“I found myself without courage to question or disagree with the plan of action urged upon me by Mr. Howser, although I did state repeatedly to him that I was innocent,” he later said in an affidavit.

His lead attorney had been in Monterey, out of the loop on his client’s plea, and read it in the next day’s newspaper.

Once the other defendants went to trial, Howser claimed, he realized his error in urging a guilty plea. He indicated he didn’t fully review the grand jury testimony, but said the prosecutors had claimed to have an ironclad case. “I am trying to vindicate rightfully the sorriest mistake that I have ever made in the practice of law.”

The trial court judge, H. Burton Noble, was not swayed, remarking at one point, that Hank “took a calculated risk and lost.”

In 1959, the year Rick Caruso was born, his father’s appeal reached the state Supreme Court, to no avail. He was sentenced to 10 years’ probation, conditioned on one of those years in county jail, and he lost his dealerships and much of his fortune.

Hank found his second act about 1966. He opened a rental outfit in downtown L.A. with 18 Volkswagen Beetles and a catchy name, Dollar a Day Rent a Car. Within a year, he had five more locations. Soon, he was selling franchises across the nation.

By 1970, business was booming — the same year that Hank’s probation ended. He was allowed to plead not guilty and his case was dismissed, putting the ordeal behind him, Los Angeles magazine reported.

Through this period, the elder Caruso sought to shield his children from the case, his son said. Still, Rick remembers classmates teasing him about it, even in first grade. “I didn’t understand it,” he said. His teacher, a nun, intervened.

Hank drove the kids to grammar school each day. Gloria would cook dinner for Rick and his siblings, Christina and later, Marc. When their dad returned home late at night, the family would sit with him as he ate dinner.

In the family lore, a young Caruso — no more than 7 or 8 — stood with his father in their yard in Trousdale Estates, the Beverly Hills neighborhood that was once the Doheny Ranch, and looked out at the city expanse. He promised to one day give his dad a building.

“I’m gonna develop all this property,” his sister Christina recalls Rick telling their father.

After Harvard School, the elite all-boys high school, Rick enrolled at USC and he joined the fraternity Sigma Alpha Epsilon. Caruso was a natural leader, friends recalled, and he had an easy rapport with those in power, from the university president to upperclassmen.

“His parents imbued him with a sense of self-confidence,” said Tegan West, who first met Caruso in high school and later joined him at USC. “He’s a boy in an Italian family, and there are expectations that come with that.”

**

Hank Caruso wanted many things for his elder son, among them: to be a lawyer, to take over his company. And to be anonymous. For a time, Caruso said, “I was a compliant son.”

After law school at Pepperdine, he began work at Finley Kumble, a prominent and politically connected firm. But the prospect of billing 2,400 hours a year reminded him of being a fraternity pledge, and he felt his work paled in quality to that of his colleagues.

Around this time he was also appointed to the Department of Water and Power commission — the first of several posts that he cites now as preparation for the job he’s trying to win.

His father was less supportive of these political pursuits.

“His dad knew if Dollar was going to succeed in the next generation, it needed a leader with Rick’s qualities,” said Bill Allen, one of Caruso’s best friends.

Rick was more keen on real estate, and his father’s guidance proved pivotal as Caruso carved an exit plan from the legal world and built the foundation of an empire.

The pitch to his dad involved buying parking lots around major airports where Dollar needed space. The younger Caruso would become Dollar’s landlord and with the lease from the company as his backing, he could approach banks and secure loans.

“I didn’t want my dad to invest in my company,” he said.

When the model worked, Caruso said he approached Budget and Enterprise. In 1990, when Dollar had become the fourth-largest car rental firm in the nation, his father sold it to Chrysler for an estimated $70 million. His son held on to the real estate.

“Little by little, I sold those lots and then invested in retail,” he said. “It was a way to get my start without having any outside investors.”

::

In the mid-1990s the Pepperdine alumni magazine asked Caruso where he saw himself in a decade. His response: “Enjoying life” in Italy with his kids.

His son Alex was born in 1989, followed by three more children, Gregory, Justin and Gianna. Like his father, he drove his kids to school each morning. His favorites — Frank Sinatra or Ray Charles — were often the soundtrack of these trips.

“He’s not a helicopter parent. But from the time that we were young, he always made it a priority to be home to have dinner with the family,” said Alex, 33, now an attorney.

Decamping abroad with his wife, Tina, and children never happened. Instead, Caruso transformed a dilapidated lot off Ventura Boulevard into the Encino Marketplace. Its success begat complexes in Westlake Village, Calabasas and the Grove in Fairfax.

“His father worried for him. He put everything he had to build the Grove,” Allen said.

Caruso said he viewed the risks differently. “If I listened to everyone who told me what not to do, I’d still be practicing law,” he said.

Throughout this steady rise, Caruso remained close with a crew that includes classmates from USC, including Allen and businessman Lew Horne. They shared meals, family vacations, and the pains and joys of life. “Part of what has bonded us is as fathers,” Allen said.

In the mid-2000s, Horne phoned Caruso with the news that his teenage son had taken his own life. In the aftermath of the tragedy, Caruso helped organize a funeral, set up a trust to fund-raise in the son’s honor and visited Horne every day for months.

“As a father and husband that was doing everything I could to comfort my own family, Rick was comforting me,” Horne said.

Caruso still remembers the eulogy Horne gave for his son — and how it changed his view about parenting.

“‘I wish I had been more of a cheerleader, rather than a coach,’” Caruso remembered his friend saying.

Caruso said he sometimes defaulted to the “old stubborn Italian dad” persona — a mentality informed by his own father and grandfather. “And as my kids were doing things that I didn’t really agree with,” he said, “I really reflected on that a lot.”

::

Once the Grove was built, Caruso’s father maintained an office there, and he continued commuting to his Long Beach car dealerships well into his 90s. Hank insisted on being behind the wheel, but it grew untenable, friends recall. So his son hired him a driver.

In the later years, Father Matt Elshoff, a Catholic priest close to the family, would meet Hank often at the Grove for lunch at the Cheesecake Factory. Hank would survey the environment, with its multigenerational throng of shoppers, manicured flower beds, the soft croon of Frank Sinatra in the background.

“‘Rick holds the vision for this place,’” Elshoff recalled Hank saying.

Rick Caruso and Karen Bass are running for Los Angeles mayor. Here is your guide to the race.

It’s a vision that yearns for a bygone era, even if his own family’s experience of high-profile scandal in the late ‘50s was messy and complicated. It’s also one that may inform what he wants Los Angeles — and its institutions, which he reveres — to look like.

Bryan Lourd, a USC classmate who now runs Creative Artists Agency, noted his friend’s “obsession with nostalgia.”

“The way those places look that he’s overseeing — it harkens back to some other time that was safer and cleaner, and in a way, simpler,” Lourd said. “The most surprising thing about him is that he’s the least cynical man I know, and the most earnest and optimistic person.”

Writer Ed Leibowitz — who profiled Caruso in 2007 — saw a sense of duty in Caruso’s work as a developer, and a desire to restore the family name.

“A dealership can change hands, but he’s building not just malls but monuments to the Caruso name as much as anything,” Leibowitz said.

The retail complexes, which included personal touches throughout — the family crest, statues of his children — were a point of pride for his father. They signified how far the family had come; entering politics would somehow stray from that success.

At earlier moments, when Caruso joined civic boards and later, when Mayor James K. Hahn appointed him to the police commission, Caruso said his dad “was not real supportive.”

“Hank was not a fan of Rick running,” Elshoff said, adding that Hank would remark how successful his son had become in business and wonder why he’d want to work in a space so bogged down by bureaucracy.

It was a disagreement that seems partly born out of an aversion to what can happen when the spotlight shines too bright, heightening a fall from grace.

Both also seemed mindful that rivals and enemies alike would weaponize his father’s criminal case. His father still carried embarrassment. Neither discussed the case until his dad was in his 70s or 80s — “and not in a lot of depth,” he said.

A decade ago, Caruso gave serious thought to running for mayor.

His father had been a Republican his entire life, and up until then, Caruso had been one as well. But as he mulled a run, he changed his registration to decline-to-state. He later returned to the GOP from 2016 to 2019 and Bass has attacked him for this flip-flopping and support of other Republican politicians. Caruso became a Democrat this year.

In 2013, he had prepared a campaign kickoff, only to pull the plug. His kids were still young, his business was growing, and his parents were in their late 80s and 90s.

In 2017, Caruso’s mom died that summer, and his dad died three months later. The family held a public funeral for both at St. Monica’s, and Caruso delivered a eulogy. Standing by an altar adorned in white flowers, he told his family story, not skipping over his dad’s worst moment. He recounted the case by first intoning, “Sometimes life is hard.”

On the day of the primary in June, Caruso walked into Boyle Heights Senior Center flanked by two of his sons—whom he hugged after casting his vote. His grandparents had lived just a few blocks away.

Outside the senior center, a reporter asked what his dad would’ve thought of this moment. He began to cry.

He bemoaned that all people saw was the oft-applied “billionaire developer” label. People didn’t see the love and commitment behind his decision, he said.

“It was emotional and to have two of my sons with me,” he said, “and think about where the family has come.”

And yet, Caruso said in a recent interview, he believes his father would probably not have come around to him running for mayor. “In a very loving way, no,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.