RSV is on the rise. How to recognize it and treat the symptoms

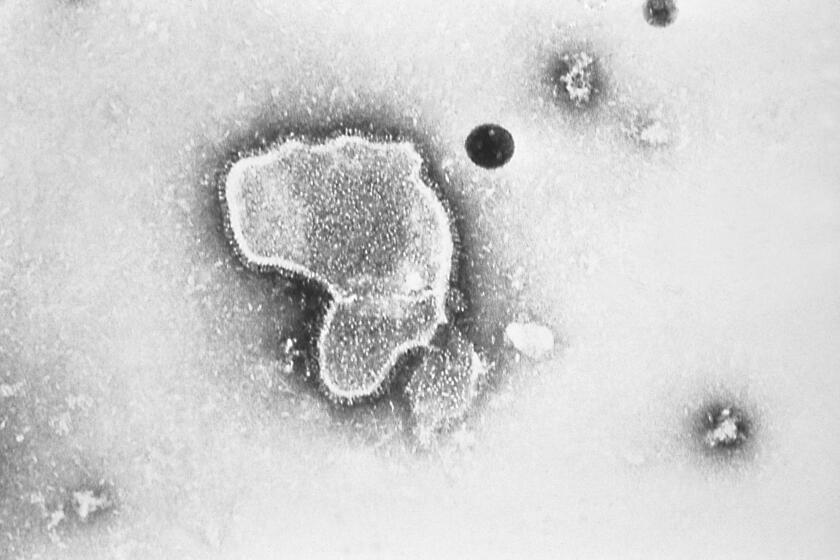

As people confront the cold and flu season, what’s top of mind for many Californians this year is the unseasonably early activity of respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which causes a respiratory illness that can be dangerous for babies and older adults.

The record number of daily emergency room visits and pediatric hospitalizations caused by the virus prompted the Orange County Health Care Agency to issue a Declaration of Health Emergency on Oct. 31, just two days after strongly encouraging residents to follow preventive measures against RSV.

In October, The Times reported some children’s hospitals in the state were straining or stretching resources because of the influx of patients sickened by RSV.

For many Californians, though, the scourge seemingly came out of nowhere. To help you prepare for this latest threat, here’s an explanation from health experts on what RSV is, which populations are at risk, what symptoms to look out for and which preventive measures to take against the virus.

The rise of the new coronavirus subvariants is raising concerns of a possible COVID-19 resurgence in fall and winter, as past surges were driven by emerging variants.

What is RSV?

RSV is a common virus that affects both the upper respiratory system, which includes the nose and throat, and the lower respiratory system, which includes the lungs, according to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. The RSV season is a long one, occurring in most regions of the United States in the fall, winter and spring, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

The virus usually causes mild, cold-like symptoms, and most people recover in a week or two. In some cases, adults can be infected with the virus and not have symptoms.

The virus is highly transmissible. You can catch it if the droplets from an infected person’s cough or sneeze get in your eyes, nose or mouth; if you touch a surface (such as a doorknob) that has the virus on it and then touch your face before washing your hands; or if you have direct contact with the virus (for example, by kissing the face of a child with RSV).

RSV can survive for many hours on hard surfaces such as tables and crib rails; it has a shorter life span on softer surfaces such as tissues and hands.

An individual infected with RSV is usually contagious for three to eight days. However, some infants and people with weakened immune systems can continue to spread the virus for as long as four weeks, even after their symptoms go away.

Virtually all children get an RSV infection by the time they are 2, the CDC said. But the virus can cause complications in vulnerable populations, including infants, children under 2, people over 50, those with weakened immune systems and those with heart or lung disease.

Children at particular risk include:

- Premature infants

- Infants 6 months and younger

- Children under 2 with chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease

- Children with weakened immune systems

- Children who have neuromuscular disorders, including those who have difficulty swallowing or clearing mucus secretions

If you’re concerned about a child’s risk for severe RSV infection, consult the child’s healthcare provider.

In infants, RSV can cause bronchiolitis (inflammation of the small airways in the lung) and pneumonia. In adults, RSV can sometimes lead to such serious conditions as asthma, chronic pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure.

An FDA panel recommends that a drug approved to prevent premature birth be removed from the market because it doesn’t work and carries risks.

Signs of RSV

RSV infections in children may not be severe at first, the CDC said. Early symptoms of RSV in children can include a runny nose, reduced appetite and a cough, which may progress to wheezing.

Infants less than 6 months old will almost always show symptoms that can include irritability, decreased activity, decreased appetite and apnea (breathing that stops and starts). Fever is sometimes a symptom as well.

Adults with RSV develop similar symptoms, including runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever and wheezing. Generally, symptoms begin to appear four to six days after becoming infected.

Symptoms that can prompt a trip to the emergency room include severe dehydration and difficulty breathing. In babies, a warning sign is not having a wet diaper for eight to 10 hours straight.

The CDC says these symptoms usually appear in stages, not all at once.

It might be difficult to tell whether a person’s symptoms are caused by a common cold, flu, COVID-19 or RSV, as all these ailments share one or two symptoms. CHLA says the only definitive way to know what you have is by testing.

A new Biden administration rule will make more families eligible for subsidized health insurance through the Affordable Care Act. Covered California estimates that more than 600,000 Californians could benefit.

How is RSV treated?

There is no specific treatment for RSV, but you can take steps to relieve its symptoms.

For children and infants, CHLA recommends that you:

- Manage a stuffy nose by using a saline spray and a bulb to suction out the mucus.

- Use a humidifier, since it may help soothe respiratory passages.

- Keep kids hydrated. Babies can be given frequent breastmilk or formula, but don’t overfeed them because they can easily vomit when they have a cough or runny nose.

- Consult your pediatrician about your child’s dose of pain reliever, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

The advice for adults with RSV is simpler:

- Manage fever and pain with over-the-counter fever reducers and pain relievers such as ibuprofen.

- Drink fluids to prevent dehydration.

A new study suggests vaccinating pregnant women protects their newborns from the common but scary respiratory virus called RSV.

Preventive measures

In an advisory on RSV, the California Department of Public Health encouraged parents and caregivers last month to keep young children with acute respiratory illnesses out of child-care, even if the child has tested negative for COVID-19. It also discouraged healthcare personnel, child-care providers and staff of long-term care facilities from working while acutely ill, even if the individual had tested negative for COVID-19. Essentially, it says to stay home if you are sick.

You can also prevent transmission by washing your hands often, keeping your hands off your face (to avoid spreading germs), avoiding close contact with sick people, covering your coughs and sneezes, and cleaning and disinfecting surfaces.

The Orange County Health Care Agency also urges you to get your flu shot and COVID-19 vaccines to prevent complications from these viral illnesses.

The prescription drug palivizumab, also sold under the brand name Synagis, can help protect some babies at risk for severe RSV disease. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that doctors administer it to eligible infants anywhere RSV is prevalent.

According to the CDC, healthcare providers usually give this monoclonal antibody to premature infants and young children with certain heart and lung conditions as a series of monthly shots during RSV season. The medicine does not prevent children from becoming infected, but it can slow or stop the spread of RSV in their body.

Although there isn’t a vaccine that can prevent an RSV infection, preliminary research by Pfizer suggests that inoculating pregnant women with its experimental RSV vaccine was nearly 82% effective at preventing severe cases of RSV in their babies’ first 90 days of life. The findings won’t help this year, but they could set the stage for one or more vaccines before next fall’s RSV season.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.