Jack Laflin likes to recall the time he wriggled into a 9-foot-long, 30-pound blue mermaid tail. He’d spotted similar pieces behind the scenes of the acting gigs he was trying to land, but this was his first attempt to maneuver his way into a silicon tube.

He wondered if using a bit of water would help ease the process — and it did, until the water dried, further constraining his legs and torso. Alone in his apartment and lying on his living room floor, Laflin considered his lack of mobility and thought, “If there’s a fire alarm, I won’t be able to get out of here.”

Laflin had purchased the custom-made piece from Mertailor around the time he was thinking about a career change. “When I first moved to L.A., I was modeling and acting, and I figured out pretty quickly that I didn’t like the way the industry viewed me,” said Laflin, who is mixed race. “I was cast either as a thug, a gangster or I was a piece of meat at the nightclub.”

Amid the other props, the mermaid tail represented the possibility of change. He’d been a competitive swimmer while growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area and was confident of his water skills. Why not marry that experience with his interest in entertainment and try out that merfolk persona in other settings? Why not try to have more fun with it? After all, he reminded himself, this is Los Angeles.

Laflin squirmed and flailed around on the floor for 45 minutes that first time. When he could finally sit up, he looked down his torso to inspect himself. Half fish, half man, it was a transformation that turned out to be life-altering.

Ten years after he first tried on the set piece in his apartment, Laflin, 40, is a full-time merman, part of a hub of mermaid enthusiasts in Southern California who inhabit personas that express everything from a yearning for childhood play and entertainment to environmental advocacy and gender identity. Going by the stage name “Merman Jax,” he runs a business that he christened Dark Tide Productions, which employs a team of about 10 men and women who perform at events such as birthday parties, corporate galas, and Renaissance fairs, sometimes in water, sometimes posing by a pool or the entrance of an event.

Mermaids tend to be more in demand, Laflin says, because most clients prefer to go with a performer who is female-presenting. But he loves the moments when he is swimming in a tank or lounging poolside because of the sense of wonder it can inspire.

“It’s one of those magical things,” Laflin said. “No matter who it is, most people turn into a kid when they see you.”

Sammy Silva’s childhood bedroom was a sea of redheads, filled to the brim with toys, figurines and blankets from the “The Little Mermaid,” the 1989 animated Disney film.

The lifelong fan of mermaids realized that their obsession might amount to something more than a collection when, as a teenager, they spotted a boy using a monofin — which resembles a pair of swimming fins merged together into a single, flat pane — to swish across a public swimming pool. Silva, who identifies as gender nonconforming, was inspired. They looked up YouTube tutorials on how to create a mermaid tail and crafted their first one using green wetsuit material and a wad of masking tape.

“It [felt] natural,” Silva, 34, said, recalling the first time they swam in costume. “It’s freeing and playful and very much like inner-child joy.”

That joy blossomed into a practice, and Silva has actively been part of the mermaid community over the last 15 years.

“It’s one of those magical things, no matter who it is, most people turn into a kid when they see you.”

— Jack Laflin, merman

They helped launch MerNetwork, a forum that has been a prominent for mermaid enthusiasts over the years. “There was a point in time where I knew everybody with a tail,” said Silva, who lives in Anaheim.

The community has grown into a global phenomenon, but Silva says the new additions are welcome — as is the increase of tails and accessories for purchase.

Today, it’s not unusual to see monofins for sale near the beach or a variety of mermaid dolls lining the shelves at gift stores connected to aquariums. Manufacturers of silicone mermaid tails, once a prop found only in Hollywood, can now be custom ordered and fitted for thousands of dollars. Other companies provide beginner-level tails priced at around $50.

Although much of the subculture has moved onto Facebook, the pages of MerNetwork are still filled with tips on how to build a seashell-laden crown and suggestions for “tail-friendly” places to swim in cities across the United States. A section of the forum dedicated to “tail making” has an archive of 1,600 conversation threads and 47,100 individual posts on the topic.

Mermaid meetups are organized into geographic “pods.” The MerNetwork forum hosts pages for the Pod of Cali, the Rocky Mountain Pod, the Chesapeake Pod and the Union of the Pods of the North, representing mermaids across Canada. Facebook groups range in size from a dozen to more than 2,500 people seeking to buy and trade mermaid tails or host gatherings in cities across the United States.

One of the largest, the California Mermaid Convention, is held in Sacramento. What began as the “Promenade of Mermaids” among a few friends in 2011 has grown into a three-day gathering of merfolk that attracted 350 attendees in May, according to Rachel Smith, one of the co-founders of the convention.

This year’s convention marked the first time Silva attended with a new identity. During the pandemic, they came out as nonbinary, changed their name and had top surgery. It had been a year since their procedure, and although the surgical area had healed, Silva was nervous. “I had existed as a mermaid for so long. I didn’t know how people would accept me.”

Entering the pool area on the first day, Silva wore a rash guard and surf trunks. But as the convention — which included a diversity panel with other transgender merfolk — continued, their confidence grew. By the last day, uplifted by the well wishes of the convention’s organizers, Silva entered the pool in full mermaid gear — with a tail and no shirt.

That old feeling of playing in the water returned, that sense of being a grown-up kid playing “mermaids” in the pool.

It was, Silva said, “liberating.”

When Gabrielle Rivera dons her mermaid tail and crown, she turns into Nymphia, a persona she developed for performances.

As Rivera, 27, tells it, Nymphia is the reincarnation of a Greek sea goddess, Amphitrite. In human form, she falls in love with a Viking prince, who starts to drown in the ocean. The sea god Oceanus will allow Nymphia to save him if she sacrifices her memories and her human form and becomes a mermaid.

The character combines some of the plot points of “The Little Mermaid” with elements of fantasy and Greek mythology, she said.

Rivera first dabbled in mermaiding as a cosplayer. She grew up in San Diego and, as a teenager, filled her summers attending Comic-Con and spending long days at the beach pretending to be mermaids with her friends. “I was always trying to swim with my legs crossed even though it doesn’t get you that far,” she said.

Then she tried out a new role based on Ariel, the main character of “The Little Mermaid.” At the time, Rivera, who is transgender, had been presenting as male. But in costume, Rivera would use she/her pronouns and discovered a new sense of self, beauty and power. “I realized I wasn’t portraying a character. I was portraying an extension of myself.”

She began her transition soon after.

Mermaiding has grown into a complete social community for Rivera, and, because she performs professionally, it’s also a source of income. Her costume includes a red coral tiara, a necklace with red gems, a bikini top decorated with plastic kelp — and a 35-pound silicone tail. (If you’re wondering, many performers pair with a partner — sometimes referred to as a mer-handler — who will help them navigate from point A to point B. A big fin is conducive to flipping, twisting, draping and posing. Strutting? Not so much.)

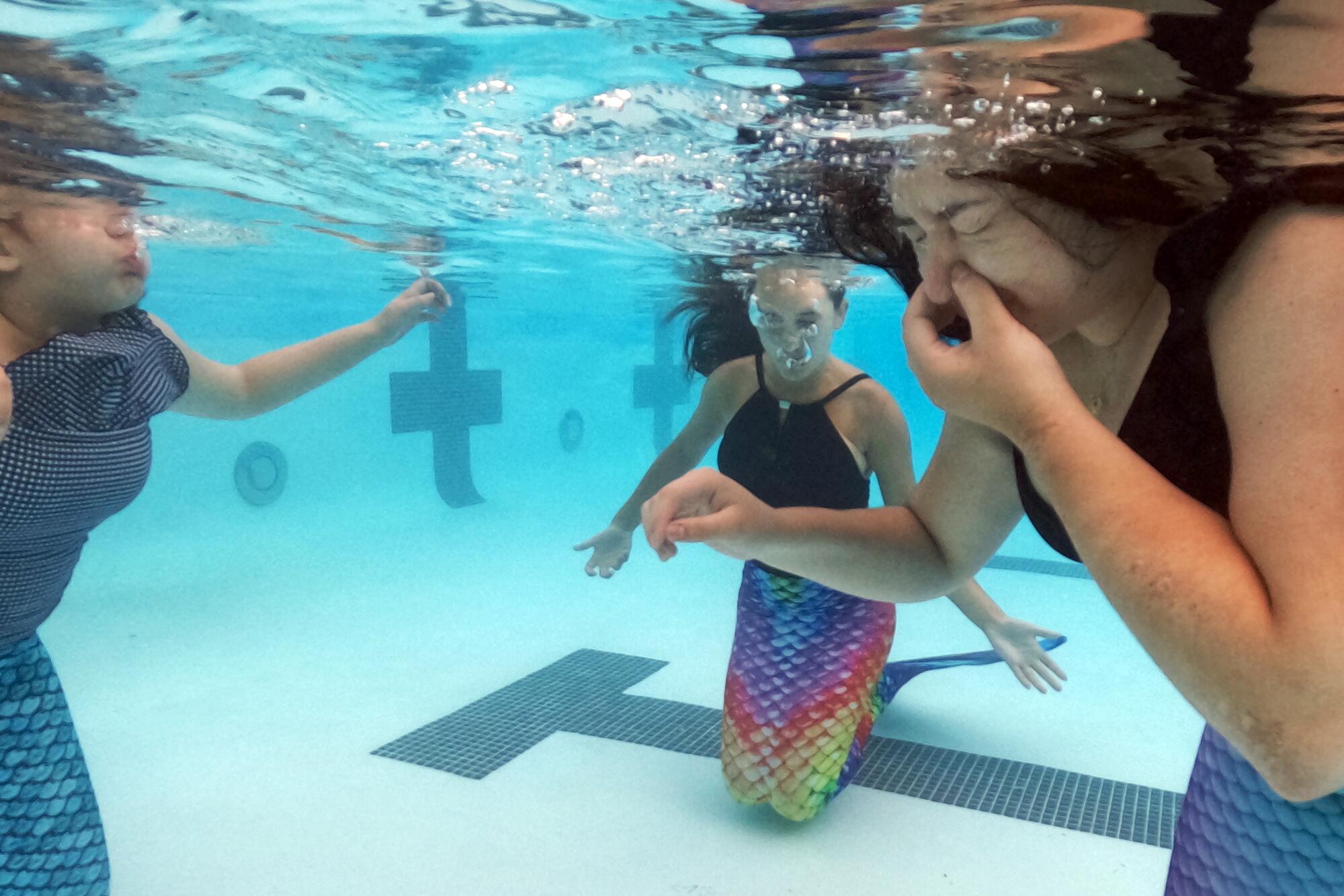

Virginia Hankins, owner of the LA Mermaid School, has many clients who are event performers and actors. During the last two years, however, she’s seen a shift as more individuals and “amateur” mermaids, rather than paid performers, contact her company.

The school offers safety courses for mermaids in training, covering everything from swim techniques to breathing work to how to blow heart-shaped bubble kisses. The company works with approximately 900 clients per year, including teenagers seeking a new spin on swimming lessons and performers looking for safety certifications.

Smith, the convention co-founder, says that people are drawn to mermaiding for many reasons, the most prominent of which seems to be the longevity of the archetype. (She’s been the lead at Sacramento’s Dive Bar — equipped with its own mermaid tank, of course — since it opened in 2011.) “Aquatic people have been part of our myth and discourse forever because humans, and every living thing, is dependent on water,” she said.

Others appreciate the athleticism required in the hobby. The 25-minute underwater routines that Smith choreographs demand that performers swim with playfulness and ease, while also balancing the buoyancy of the mermaid tail and timing to go up for air.

The best part? That, Smith says, is when it appears effortless.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.