KNEELAND, Calif. — In Kneeland, which isn’t so much a town as a rural fire station and a smattering of homes in the forest, the school has long been the lifeblood of the community.

And it has long felt a little fragile.

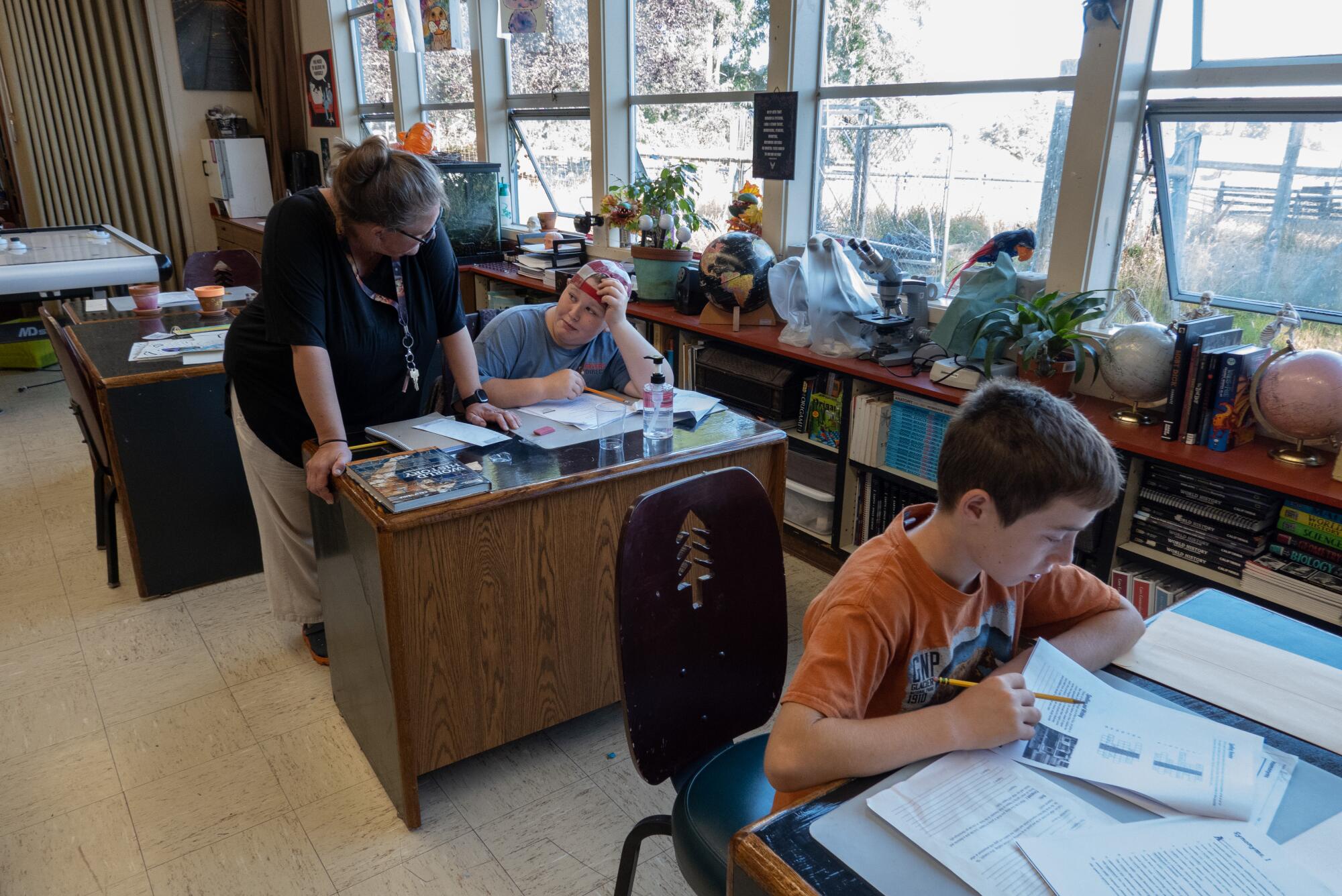

Perched on a mountaintop in Humboldt County, amid coastal redwoods and Douglas firs, Kneeland Elementary is one of California’s smallest public schools.

Two years ago, the school, which was built in 1880, was on the verge of closing. It had an average daily attendance — for the entire school, transitional kindergarten through eighth grade — of 12 students.

Then, up the mountain came the pandemic kids, who had been withering away in front of Zoom screens. They found refuge in a school that, because it was so tiny, had quickly resumed in-person classes.

On the grassy, 2.5-acre campus, students did a biology unit on bugs (since there are a lot in the woods). When it got cold, they moved inside, where it was easy to socially distance, since there were so few of them.

Since 2020, enrollment has more than doubled, to 33 students. The school got more funding. It hired a teacher — there are now three — and built a new classroom.

“Once enrolled, these fabulous families recognized how unbelievably awesome we are, and stayed, which thrilled us to pieces,” said Supt. Greta Turney, who also teaches sixth through eighth grade.

What happened in Kneeland is a bright spot in California, where public school enrollment has plummeted over the last five years. Last fall, the state’s K-12 population dipped below 6 million for the first time since 2000.

The steepest declines came amid the pandemic as students struggled with online learning, with large urban districts accounting for much of the drop. In the Los Angeles Unified School District, nearly half of students were chronically absent last year.

Nearly half of L.A. students were chronically absent last year. Educators say they must bring children back to class.

Rural schools also lost students to home-schooling amid a backlash against COVID-19 mask and vaccine mandates. But many families have begun bringing their kids back, and some small districts, like Kneeland, actually grew, said Tim Taylor, executive director of the Small School Districts Assn.

“In the small schools, you pretty much know where everyone is or was,” Taylor said. “The superintendent and the board know the names of every kid. That’s a different ballgame. But you still have to attract them back because it was such a bad go with COVID.”

In Kneeland, the critical number is eight students. At that point, only waivers from the county and state can keep the doors open, said Turney, the superintendent.

State funding is tied to attendance. A single family leaving the area can break such a small school.

When average daily attendance dropped to 13 in the 2018-19 academic year, teachers desperately tried to get the school’s name out there.

They decked out their only bus in colorful lights and drove through the Christmas Trucker’s Parade in Eureka, 17 miles west. They were all over local radio, talking about their fall festival. To show off the drama program, students wrote a play, then directed and performed it in Ferndale, an hour’s drive down the mountain.

“Seeing it struggle with so few students, it was really upsetting. We were working really hard to make sure that they could keep open, because a lot of families don’t really have other options,” said Perrin Turney, an instructional aide, alumnus and the superintendent’s son.

Most schools, including rural ones, did not grow during the pandemic.

Deeper in the woods, a half-hour drive east on perilous mountain roads, Maple Creek Elementary is even more remote than Kneeland.

The trek, which includes unpaved roads on some routes, is too difficult to attract students from farther away. The school is barely hanging on, with six students and a waiver.

The student body shrank decades ago after a local sawmill closed. Many of the remaining families have been ranching and farming for generations.

Three years ago, Maple Creek Supt. Wendy Orlandi took all her students to the California Department of Education in Sacramento, where they successfully pleaded for a one-year waiver to stay open. Some had never been in a high-rise building, and the elevators were a thrill.

“I’ll be on the playground and think, ‘This may be my last year. This may be my last recess. We’re going to make the most of it,’” said Orlandi, who treasures the one-on-one time she gets with students.

Sixth-grader Asha Quinlan was one student who found Kneeland Elementary during the pandemic.

In fall 2020, his mother, Nicole Quinlan, watched with alarm as her outgoing boy, who has a quick wit and contagious giggle, started declining — fast.

His 400-student elementary school, near the college town of Arcata, started the semester online. With the constant technology issues in their rural home, which has spotty satellite internet service, and the loneliness, his days ended in tears.

“We gave it a fair shot,” Quinlan, 50, said of distance learning. “We gave it a few months, but he wasn’t thriving. He was actually crying. I’m not being dramatic — it was traumatizing.”

Quinlan cold-called Kneeland Elementary and found out classes were in person. They got an interdistrict transfer and never looked back.

Now, she drives her son about 15 minutes to a school bus stop at a country market, and it’s a half-hour bus ride from there.

The mountain road takes its toll, and when the bus’ brakes have worn down, she has shuttled Asha and other kids all the way up.

She gave him the choice to return to his old school this year. He said, “Oh, heck no.”

At the start of the pandemic, Kneeland had to be vigilant about COVID-19 precautions — holding classes outdoors or socially distancing indoors — because it had no choice.

“If teachers get sick, we don’t have any substitutes,” said Cherie Circe, the district secretary.

With its bigger enrollment — and bigger budget — the school was able to hire a third teacher this year.

Each classroom has three grade levels — for example, one class has 10 students in third through fifth. This year, despite the new students, there are no eighth-graders.

Everyone “wears a lot of hats,” as they like to say.

Perrin Turney is a math teaching aide, maintenance supervisor and certified water operator who does all the treatment for the school’s own public water system.

The custodian is also an instructional aide. The secretary is also the transportation director and a teaching aide.

School officials are urging Gov. Gavin Newsom and California legislators to require that the state fund school buses for all districts.

And the bus driver, Jesse Dodd, 29 — a self-described Dungeons & Dragons-loving nerd — just designed a fantasy game for Fun Math Fridays. It involves arithmetic and, since the kids are doing a mycology unit, a knowledge of fungi, with their characters trying to save mycelia that live under the forest floor.

“Kids really respond to big ideas, big stories, big images, and being able to connect those lessons with something kind of weird and magical really helps that stick in their heads,” Dodd said.

And then there’s the ultimate multiple hat-wearer: Greta Turney, whose three adult children attended Kneeland.

Along with being the superintendent and a teacher, she’s a lab tech in a veterinary diagnostics laboratory. And she’s a singer and actor and prop designer for local theaters. And, oh yeah, she breeds Burmese cats.

She gets to school early, in case students need before-school care. She stays late, too.

On a recent morning before class, she swept up barn swallow poop —the birds have been building a nest in the rafters — and spoke of the time, a few years ago, when a juvenile black bear wandered onto campus, got startled when a teacher’s aide screamed and climbed a tree on the playground, where it stayed until they all left.

As her sixth- and seventh-graders settled into her classroom — where floor-to-ceiling windows look out on an old wooden barn — they greeted her by her first name: “Good moooorning, Greta!”

Next door, in the transitional kindergarten-through-second-grade classroom, Cheryl Furman, the custodian and instructional aide, read the book “If You Could Wear My Sneakers” between gentle reminders to sit “crisscross applesauce.”

“Why doth the sloth moveth so slow?” she read.

“I noticed you said ‘doth,’” chimed in Edward Rich, a blond second-grader.

“That’s just a fancy word for saying ‘does,’” Furman said. “Just because someone talks different, that doesn’t mean make fun of them, right?”

The kids nodded vigorously.

Teaching multiple grades in one room involves the help of aides, so students can be pulled into small groups for grade-specific lessons, and it requires teachers to come up with entirely new lesson plans annually, since teachers see the same kids for a few years.

It has its challenges. But seeing kids play and learn with students of different ages has a certain magic, said Natalie Grant, the new transitional kindergarten-through-second-grade teacher, who is an alum.

“It’s like a really big family,” she said. “The kids take care of each other.”

At lunchtime, Mark Moore, 67, a rancher and logger, popped in to say hello. His is one of the families who’s kept the school going.

Two grandchildren — a first-grade boy and a fourth-grade girl — attend now. A 4-year-old grandson will start next year. His three adult children attended Kneeland, including a daughter who is on the school board.

Moore himself was a student when it was a one-room schoolhouse. He was on the school board, as was his mother.

“The land is in your soul,” he said of the area, where his family started a cattle ranch in 1896. It’s life-affirming, he said, to come to the school to hear “the happy banter.”

As she played outside, third-grader Bailey Gingerich said her school is just the best. She and her sister, who is in sixth grade, came to Kneeland during the pandemic.

“You’ll never run out of oxygen because you can just go near a tree,” Bailey said in a high, chipper voice. “You don’t have to drive, like, miles away. We’re in nature, and everybody’s nice.”

Another newer girl, a fifth-grader, said she was so much happier here than at her other school, because she has “a playground and not just a blacktop.”

Perhaps the students’ favorite adult on campus is Perrin Turney, the 20-year-old instructional aide and handyman and, well, everything-man.

He is a math whiz with a humble demeanor, who graduated high school at 16 and has been working at Kneeland ever since. He initially planned to do it for a year or two while he studied at College of the Redwoods, but he keeps sticking around because he adores the kids so much.

On this day, he played baseball with them and led the sixth- and seventh-graders in a science project, making cardboard box pinhole cameras that they wore over their heads to demonstrate how light rays and human eyeballs work.

He’s mature beyond his years, his mother said, in part because he had to overcome a lot. He was born with single suture sagittal craniosynostosis — a condition in which skull bones fuse too early in infancy, potentially causing problems with brain growth — and had six major surgeries by the time he was 10.

Here, he has helped get students’ math scores up. And he is putting together an astronomy unit, with support from the Astronomers of Humboldt, who have an observatory on the Kneeland campus.

He loves the old, funky school that sometimes feels like it’s falling apart, in more ways than one, but always has its charms.

“It’s like an old man who’s yelling at kids to get off his lawn — but he’s actually, secretly, happy they’re playing,” he said.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.