A car-less math teacher commutes four hours. Surprise! Look what his students gave him

Math teacher Julio Castro thought he was late to the party when he walked in near the end of a faculty-appreciation assembly at YULA Boys High School. He wished he could have dropped his name into the raffle box.

But the entire event was a charade set up to honor him by surprise — beginning with video testimonials, a procession through confetti cannons and a tunnel of students with arms stretched overhead. And the finale: The gift of a certified pre-owned Mazda 3 hatchback to ease the tortuous commute of a beloved teacher.

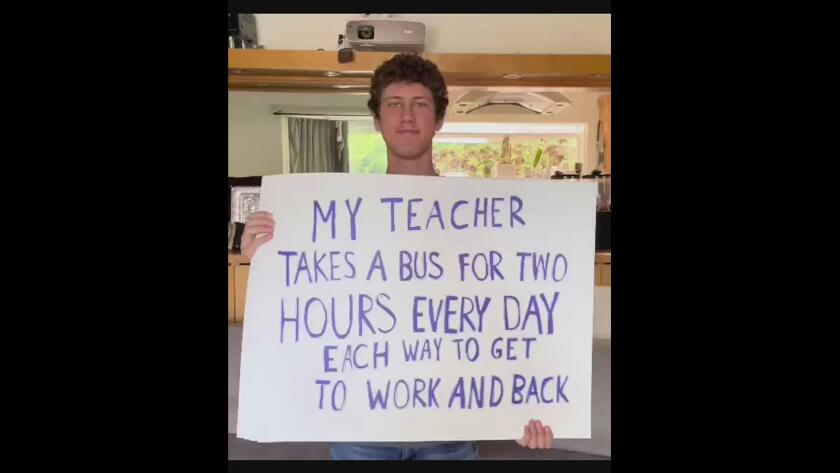

Castro lives in the Santa Clarita Valley and commutes about four hours a day by scooter and bus to get to the Westside school, because he does not have a car. He typically wakes up at 4:30 a.m. and returns home as late at 9:30 p.m., when his three young children are already asleep.

The commute starts at his apartment, from where he travels about seven miles to the Metro stop on a scooter. From there, Bus 797 takes about 90 minutes to get to Century City. Then it’s about a mile to the modern Orthodox Jewish campus on Pico Boulevard in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood.

Despite the commute, “he still makes sure to devote all this time to students,” said Joshua Gerendash, who happened to see his teacher looking wistfully at cars online, hoping to find something drivable for about $1,500. “He’ll skip his lunch break to help a student and stay after school. He also helps students who aren’t in his classes. He’s really, really, really devoted to our futures.”

So, during a months-long fundraising campaign, these social media-savvy students and their sophisticated parents produced an Instagram/Facebook post and collected $30,000 for the car and one year of donated insurance and gas to thank the teacher who every day goes many extra miles for them.

Castro knew his students were aware of his commute, from his affordable apartment to a job in L.A., a familiar necessity among many mid-wage professionals as well as for low-income workers. But he never expected them to take action.

“I made the best out of it,” he said. “I always told them: When life doesn’t go your way, what do you do? Don’t cry about it. Don’t whine about it. Just be grateful for what you already have, and then move on. And one day some good things will happen.

“And that’s proof,” he said, marveling at the dark blue 2019 Mazda with its 2.4-liter engine, inline front-wheel drive, leather seats, Bose stereo, sunroof and only 30,000 miles.

Castro, 31, added that a person should never do things in hopes of being rewarded: “Don’t do it because you’re waiting for a prize. Do it because it comes from your heart.”

Yes, the students acknowledged, they could have raised money for homeless people, or for Ukrainian refugees. But the personal connection with Castro meant something to them.

“No matter what happens with him, he is gonna find some way to pay it forward,” senior Charlie Leeds said. “We’ve been taught certain values like empathy” and to “treat your fellow person as you’d want to be treated. Mr. Castro is the embodiment of that. With this car, with this new opportunity, he’s only going to find more and more ways to help other people around him.”

As a math teacher, students said, Castro is patient and resourceful, skilled at making his students successful.

“I focus a lot on motivation,” Castro said. “Get them motivated to not need to ask for help. Because it’s not just knowing the answer, it’s about how to get to the answer and I may not tell them. ... Math is a skill you learn with practice, and being dedicated — and as long as you give respect to it, it’ll be respectful to you. And don’t worry about the grade, it’ll show within time.”

Castro traveled a circuitous route in life to end up at the school. Born in Peru and raised in various parts of southeast L.A. County, he graduated from Downey High School and had been helping classmates with math since middle school. A stint in community college led to a degree in molecular cell and developmental biology from UC Santa Cruz in 2015. He was the first in his family to graduate from high school and college.

Before long he was teaching math as an adjunct community college instructor but wanted steadier work. He applied for an opening at YULA.

“I’m not Jewish,” he told the school. “I don’t know anything about Judaism. But I know math. If you give me a chance, hopefully, you know, the students will like the way I teach.”

He added: “After the first lecture, they started singing and dancing. So that was a good sign.”

Joshua’s mother, Daphna Nissanoff, works as program manager for the Change Reaction, a nonprofit that typically provides small, fast grants to those in crisis or with a pressing need. For Castro, the group diverged from its format and offered a matching grant of up to $10,000. The nonprofit also arranged for a videographer to document the effort.

Another parent, Sarah Pachter, penned an article for a Jewish website, and the group set up a donation platform. Donations totaled about $13,000 and came from around the world.

The boys also raised about $3,000, just before the start of school, by running raffles and selling donated food at two events they organized — a 3-on-3 basketball tournament and a movie night showing of “Ratatouille.”

Shimmi Jotkowitz, a senior, took charge during car shopping and negotiations at Galpin Motors, which offered a $5,000 discount for the car the students set their hopes on.

At high-tuition private schools, the teachers and mentors whom students look up to frequently live more modestly than the students they serve. Tuition at the Jewish school is $39,000 a year, although about 65% of students receive some degree of financial aid, according to school officials, who declined to release teacher salary ranges.

Castro said his work is a pleasure and that his family members work harder than he does.

“I have family members who don’t have papers — who aren’t documented, who have three jobs, get paid less than I do, and they don’t complain,” Castro said. “I’m very grateful to have an amazing partner and amazing kids. So this commute is literally nothing.”

Rabbi Arye Sufrin, head of the school, said the effort “is really about gratitude. This is about having our students appreciate the sacrifice that our teachers and Mr. Castro, in particular, will do to ensure that they can maximize their potential and be the best version of themselves.”

Castro tried to make good use of the bus time — by napping or grading papers. So the switch to sitting behind the wheel in gridlocked traffic might not always feel like an upgrade every morning.

But the journey has been worth it, he said, enough so that he turned down a teaching job closer to home.

YULA “opened the doors for me, they accepted me as a family member,” he said. “And you can’t buy that. I want to be here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.