Column: Newsom’s Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta plan makes more sense. But it’s still a ‘water grab’

SACRAMENTO — The third attempt could be the charm for repairing California’s main waterworks, the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

On paper at least, the latest plan by a governor to upgrade the delta into a more reliable state water supply seems to make much more sense than what his predecessors promoted.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s single-tunnel proposal is smaller and more respectful of the bucolic estuary’s small farms, waterfowl habitat, unique recreational boating and historic tiny communities. So, it’s potentially less controversial.

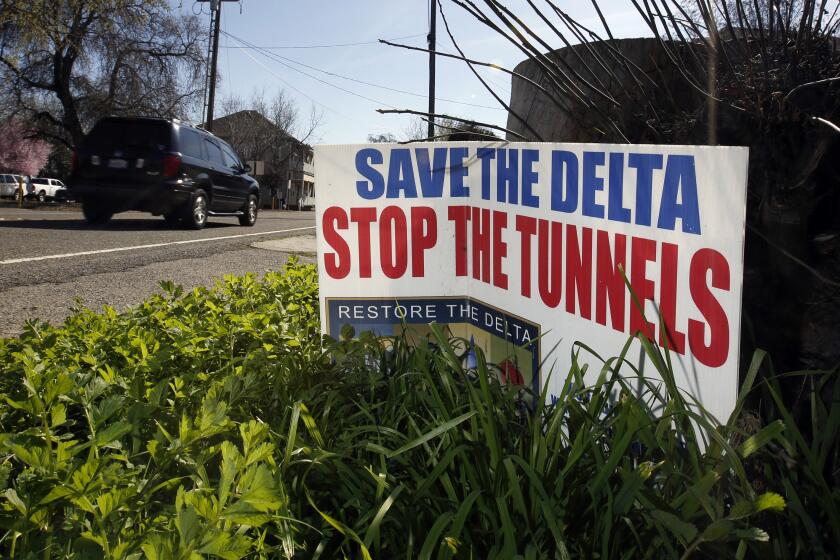

But it still can legitimately be labeled a Los Angeles and corporate agriculture “water grab.” It justifiably scares little delta towns and local farmers who rely on fresh river flows to turn back salty water from San Francisco Bay.

Delta folks can’t match the grabbers’ political power. But environmentalist allies have a loud voice and attorneys eager to file lawsuits that can gum up the works.

There’s no pretension that the governor’s delta tunnel plan is a solution for the current drought. Even if it’s eventually built, there’ll first be several cycles of drought and flooding. And Newsom will be long gone from Sacramento.

It’s possible that a second package of water projects that Newsom unveiled last week could help in the present drought, although his proposals are tailored for the hotter, drier future of climate change when there’ll be less Sierra runoff.

He called for accelerating construction of water projects, including storage above and below ground, desalination of salty sea and brackish inland water, and lots more conservation and recycling.

The delta is California’s main water hub, serving 27 million people and irrigating 3 million acres.

But its ecology has been tanking. River waters have been diverted for agriculture before they reach the delta. And the water that does reach it has been over-pumped through fish-chomping monstrosities into southbound aqueducts. The powerful pumps also reverse river flows, confusing migrating young salmon and leaving them vulnerable to large predators.

This has devastated native fish — salmon, steelhead, tiny smelt — and prompted courts occasionally to tighten the spigots on water pumped to San Joaquin Valley farms and Southland cities.

Delta replumbing ideas have been fought over for six decades, back to when Gov. Pat Brown realized that his heralded State Water Project was not sustainable for fish. It also could be swamped by the collapse of fragile levees during floods or earthquakes.

There have been three major iterations of delta fixes.

Pat Brown’s son, Gov. Jerry Brown, overreached by proposing a gargantuan Peripheral Canal that would have siphoned Sacramento River water in the north delta and routed it around the estuary in an aqueduct large enough to float an ocean liner. It had a carrying capacity of 23,000 cubic feet of water per second.

Smaller than previous versions, the project is still huge, and is sure to be litigated by environmental groups and Sacramento-San Joaquin farmers.

The Legislature authorized the canal, but voters overwhelmingly repealed the legislation in 1982.

Fast-forward a quarter century to Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. He launched a twin-tunnel idea to transport Sacramento River water under the estuary from the north delta to the southern pumps. Each tunnel would have been 40 feet wide, embedded through the delta’s heart — pear orchards, a popular scenic boating area and a waterfowl sanctuary where migrating sandhill cranes winter.

Brown pushed hard for the twin tunnels when he returned as governor, trimming their total capacity from 15,000 cubic feet per second to 9,000 cubic feet per second.

But opponents loudly protested, questioning the need for two tunnels and objecting to desecration of fragile land during decade-long construction.

Now Newsom has proposed a more practical plan: A single tunnel 45 miles long and 39 feet wide, with a smaller capacity of 6,000 cubic feet per second CFS capacity. It would be routed around the eastern edge of the delta, away from boating and the cranes, although skirting another wildlife refuge along Interstate 5.

The project’s configuration would mean less pumping in the south delta and fewer fish kills.

Cost: at least $16 billion, a huge investment paid for by water users.

Newsom says one goal is to prepare for sea rise resulting from climate change, which will make the delta saltier and require capturing fresher water upriver for transport south.

But that’s all the more reason why delta skeptics object to the state grabbing their fresh water before it can flow to local communities and farms. The state government’s view is that the water isn’t all theirs anyway.

“That water doesn’t originate in the delta,” says Wade Crowfoot, secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency. “It drains off a large portion of the state.”

State officials say they want to grab rampaging flood water and store it in reservoirs and aquifers for use during droughts. The tunnel wouldn’t operate when rivers are low, they insist. But delta people don’t trust the state.

“When they get thirsty down in L.A., the delta will be sacrificed,” says Sacramento County Supervisor Don Nottoli, chairman of the Delta Counties Coalition.

“As proposed, it would be terrible for fish and wildlife. It’s based on the thesis that fish don’t need water,” says Doug Obegi, senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“For years, biological science has been clear we need to take less water from the delta. But political science has rejected that. And as our fishery shows, political science trumps biological science.”

“The crux of the problem is trust,” says Jeffrey Mount, a water expert at the Public Policy Institute of California. “Delta people don’t trust the state to operate the tunnel well.”

But he adds: “Water is so valuable to L.A., I see this eventually getting built.”

Not without persistent gubernatorial follow-through. And that’s not always a Newsom strong suit.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.