Fueled by rapid reinfections, California’s soaring summer COVID wave could top winter surge

New coronavirus infections in parts of California may be surging even higher than winter’s Omicron wave, potentially explaining why so many people seem to be infected simultaneously.

The concentration of coronavirus levels in San Francisco’s wastewater is at even higher levels than during the winter, according to data tweeted by Marlene Wolfe, an assistant professor in environmental health at Emory University.

Wastewater data for much of L.A. County — Los Angeles city and a wide swath of eastern and southern L.A. County — have been unavailable due to a supply chain shortage on testing supplies at the state level. But county Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said last week that steady increases have been noted as of late in the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District that serves areas in and around Calabasas and the L.A. County Sanitation Districts’ treatment plant in Lancaster.

The wastewater data suggest many infections aren’t being recorded in officially reported coronavirus case counts. That is because so many people are using at-home over-the-counter tests, which can be more convenient than getting tested at a medical facility, where results are reported to the government.

“When you look at the [coronavirus] case counts, they’re no longer reliable. There are tremendous undercounts,” Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of the UC San Francisco Department of Medicine, said at a campus town hall Friday. “And the number of cases now probably is not all that dissimilar to what we saw during the massive surge in December and January.”

In Los Angeles County, an average of more than 222,000 tests were being recorded daily in January; in June, that figure had dropped to around 77,000 tests a day.

That’s why, Wachter said, he strongly recommends masking in indoor public settings “in the face of immense numbers of cases.”

At UC San Francisco’s hospitals, 5.7% of asymptomatic patients are testing positive for the coronavirus, meaning 1 in 18 people who feel fine nonetheless have the coronavirus. In other words, in a group of 100 people, there’s a 99.7% chance that someone there has the coronavirus and is potentially contagious. “Think about that the next time you go into a crowded bar or get onto an airplane with 100 people,” Wachter said.

“I kind of wish the flight attendants would hold up a sign that says, ‘I can guarantee to you that someone on this plane has COVID,’” he said. “I think the rate of mask wearing would go up quite a bit.”

The spread of illness caused UC Irvine on Monday to renew a mask mandate inside campus buildings, following the lead of other campuses such as UCLA and school systems like San Diego Unified. UC Riverside also temporarily implemented an indoor mask mandate that expired last month.

In addition, the film industry has recently begun to require masking on film sets again around Los Angeles.

L.A. County’s coronavirus case rate continues to rise. L.A. County is now averaging about 6,900 coronavirus cases a day — nearly double the peak case rate from last summer’s Delta surge, and 27% higher than the previous week. On a per capita basis, L.A. County’s case rate is 476 cases a week for every 100,000 residents; a rate of 100 or more is considered high. COVID-19 deaths in L.A. County have risen from 50 per week to between 88 to 100 fatalities per week over the past month.

California is recording about 21,000 coronavirus cases a day, up 16% over the prior week. On a per capita basis, the state is recording 368 cases a week for every 100,000 residents. California is recording roughly 255 COVID-19 deaths per week. Weekly deaths in the state have fluctuated from 200 to 300 deaths a week.

L.A. County is prepared to reinstate a universal mask mandate in indoor public spaces for those 2 and older as early as July 29 if the rate of new coronavirus-positive hospitalizations does not improve.

Officials recommend that employers take steps to reduce crowding and, if there’s a suspected outbreak, expand options for remote work.

“Worldwide, we’re clearly in the throes of the sixth wave of the COVID epidemic,” UC San Francisco epidemiologist and infectious diseases expert Dr. George Rutherford said at the meeting. “This has been prompted by worldwide circulation of the newer Omicron sublineages: BA.4, BA.5 and now BA.2.75.

“This is my way of saying: We’re not out of the woods yet,” Rutherford said, adding that the World Health Organization “recently said there’s no reason to consider we’re anywhere near the end of this.” Last week, he noted that COVID-19 remains a “public health emergency of international concern.”

It’s unclear how long this wave will last. Dr. Robert Kosnik, director of UC San Francisco’s occupational health program, said a current surge among employees and students has so far lasted twice as long as its fall-and-winter wave, which lasted about two months.

It’s easy for COVID fatigue to set in, given the duration of this wave. But, Kosnik added, “we still need to be vigilant.”

That means not coming to work if you have symptoms, Kosnik said. At-home coronavirus tests can give negative test results for people on the first day or two of symptoms, even though they are contagious. It sometimes takes two or three days after symptoms begin for enough virus to have replicated in the body for the rapid test to turn positive.

Most Californians live in counties with a high COVID-19 community level, in which the CDC recommends universal masking in indoor public spaces.

“The symptoms are quite devious in my mind,” Kosnik said, with some people who don’t know they are infected thinking symptoms are only from allergies or a cold.

“If you have symptoms, and you test negative, you need to still assume you could have COVID,” Wachter said.

The latest California models suggest the virus is spreading at even faster rates. As of Monday, the California COVID Assessment Tool, published by the state Department of Public Health, said the spread of the coronavirus is probably increasing, with every infected Californian likely spreading it to 1.15 other people.

BA.5, the Omicron subvariant driving this latest wave, “is not exactly a brand-new ballgame, but it’s definitely a new inning and we have to take it seriously,” Wachter said.

A challenge with COVID-19, he added, has been that once we learn a pattern of how the disease works, “our brain locks in on those. And we kind of assume that they will continue to be true. And then when they turn not true, it’s a little bit hard for us to pivot.”

The subvariant BA.5 made up 65% of U.S. coronavirus cases over the week ending Saturday. A month ago, it made up 17% of cases.

That’s what’s happening now, Wachter said. Some patterns are still similar — new subvariants keep emerging that are even more contagious. Also, Omicron infections seem to cause less severe disease than Delta, the dominant coronavirus variant last summer. During Delta’s peak, about 5.6% of coronavirus cases in L.A. County required hospitalization, but during the winter’s Omicron wave, only about 1.2% of cases did.

Regarding BA.5, “what is different — and this is where it is something of a game-changer — is the level of immune escape, and particularly to the degree to which immunity from prior infection, including prior versions of Omicron, doesn’t seem to count for as much,” Wachter said.

So it’s wrong to think that if you’ve survived a coronavirus infection, you no longer have to worry about COVID-19 for perhaps three months, Wachter said.

“We are seeing reinfections as early as a month after a prior infection,” Wachter said. “You can’t count on COVID ‘superpowers’ from your prior infection-plus-vaccination to make you completely free of risk for the next three or four months, which is really the way we used to think about this a few months ago.”

Wachter said it’s unclear whether reinfections, on average, are more, less or the same severity as an earlier infection.

But he cited a recent preprint study from scientists with Washington University and the Veterans Affairs Saint Louis Health Care System suggesting that people who got reinfected “did worse over the long haul.” The study suggested that reinfected people have a higher long-term risk of death — even after the acute infection has resolved — besides other health problems.

“Compared to people with first infection, reinfection contributes additional risks of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, and adverse health outcomes,” the study said, including in organ systems affecting the cardiovascular, kidney, neurological and gastrointestinal systems and increasing risk of diabetes, fatigue and mental health disorders.

The risks were evident in not only unvaccinated people but also vaccinated people who got a booster shot. “The risks were most pronounced in the acute phase, but persisted in the post-acute phase of reinfection, and most were still evident at six months after reinfection,” the report said.

“It’s worth going with the assumption that getting reinfected is a bad thing — that once you’re infected, you have a little bit of additional immunity, but not that much. And you should go back to your prior position of trying to be careful,” Wachter said.

Determining which version of the coronavirus should be used to make COVID-19 vaccines and boosters is an exercise in educated guesswork.

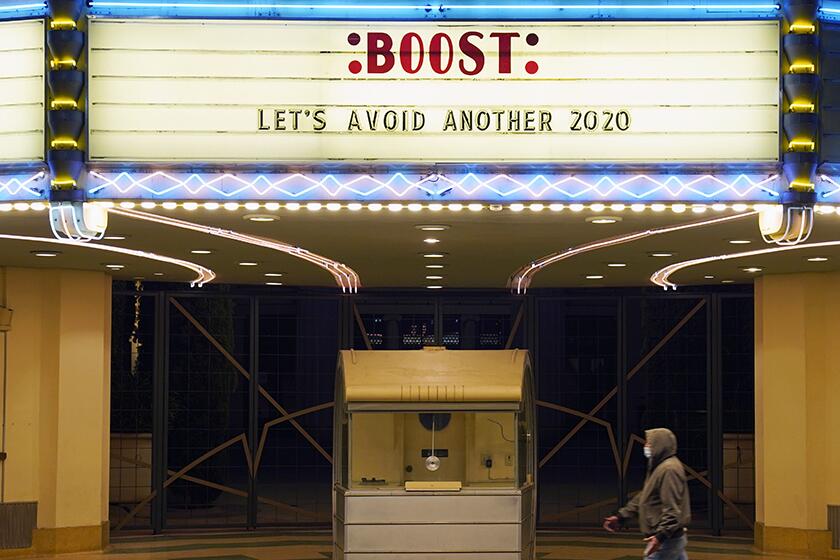

That’s why it’s important to get up-to-date on vaccinations and boosters, Wachter said. Federal officials have said to not wait for an Omicron-specific booster that might come in the autumn; if you’re eligible for a first or second booster, get it now and you can still get an Omicron-specific booster later.

The existing vaccines, even if not designed specifically against the latest subvariants, still help reduce the risk of hospitalization and death, even if they’re relatively less effective at preventing infection in the first place.

A report published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Friday found that vaccine effectiveness protecting against hospitalizations or emergency room visits declined five months after the second COVID-19 vaccine dose. That’s why it was so important to get a booster, and a second one, when eligible, the report said.

Second booster shots have been limited to people 50 and older and those who are immunocompromised age 12 and older. Wachter said that federal officials have been signaling that eligibility for a second booster will be coming soon.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.