She won a local election in a landslide. A conservative activist launched a recount anyway

The election wasn’t even close.

Last month, Natalie Adona won her race to become the clerk-recorder and registrar of voters in rural Nevada County with 68% of the vote — nearly 15,000 votes ahead of the man who came in second place.

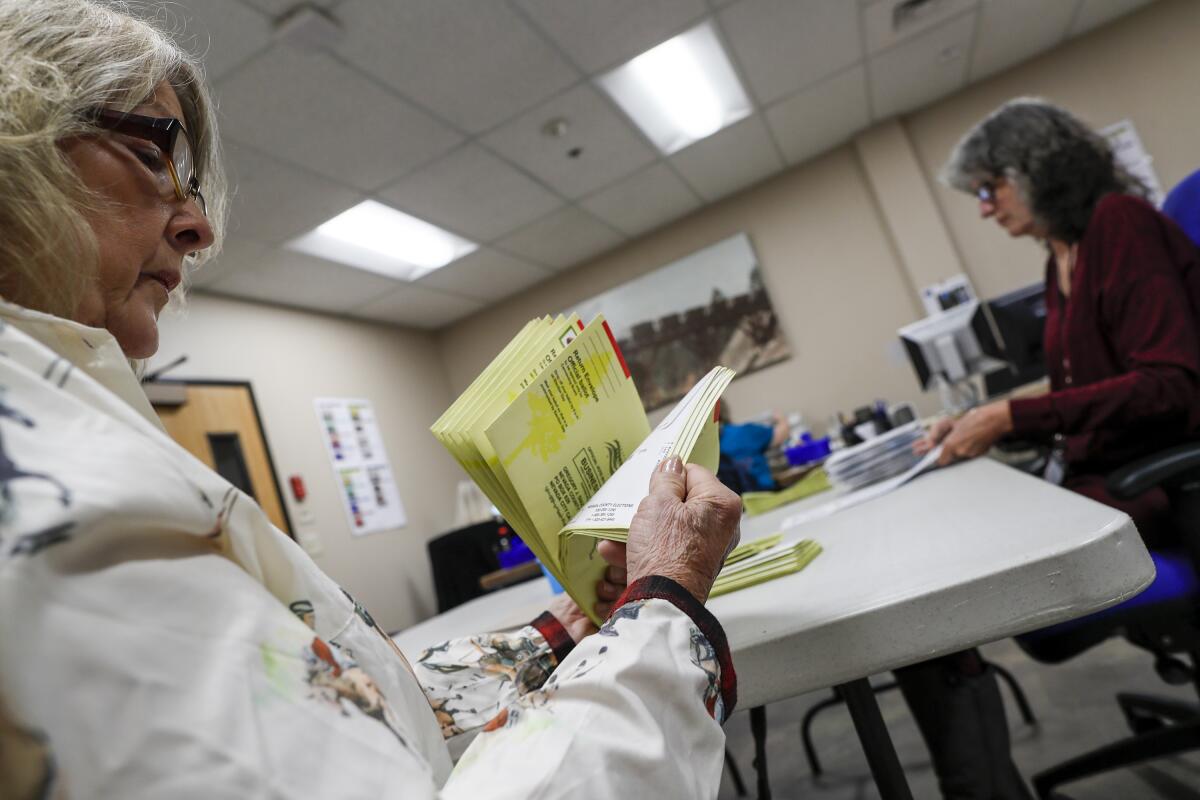

But despite Adona’s landslide victory, the race will be the subject of a potentially lengthy hand recount.

It is expected to take 38 days, cost more than $82,700, and require the hiring of temporary workers to count nearly 38,000 ballots.

And it is being funded by Randy Economy, a leader of the unsuccessful Republican-backed effort to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom last year.

Economy spoke vaguely about his motivations, saying “something doesn’t smell right” about the county registrar’s race.

“We have a crisis here in this state of who’s in charge of democracy, and it ain’t the county clerks, and it’s not the local city clerks. It’s the people,” Economy said.

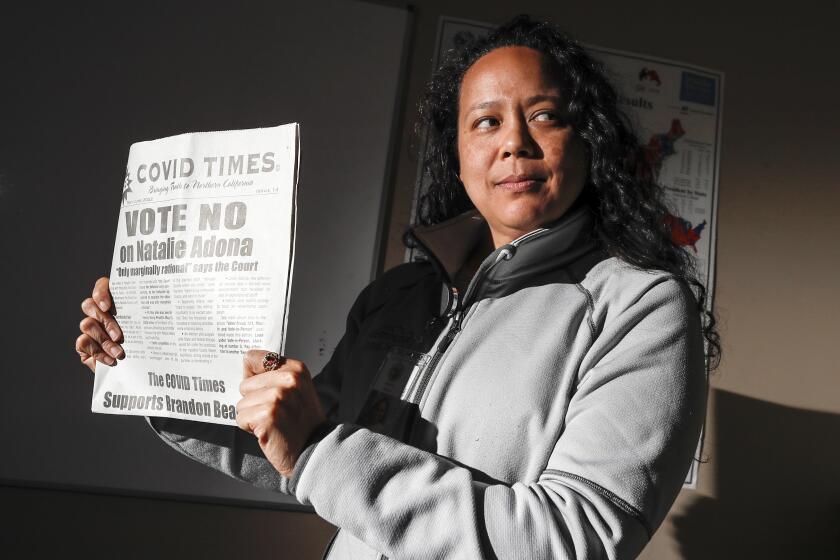

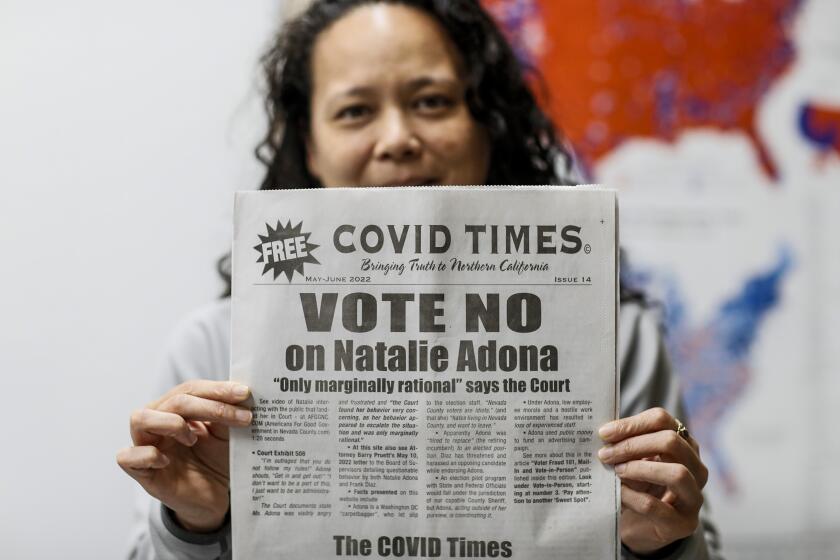

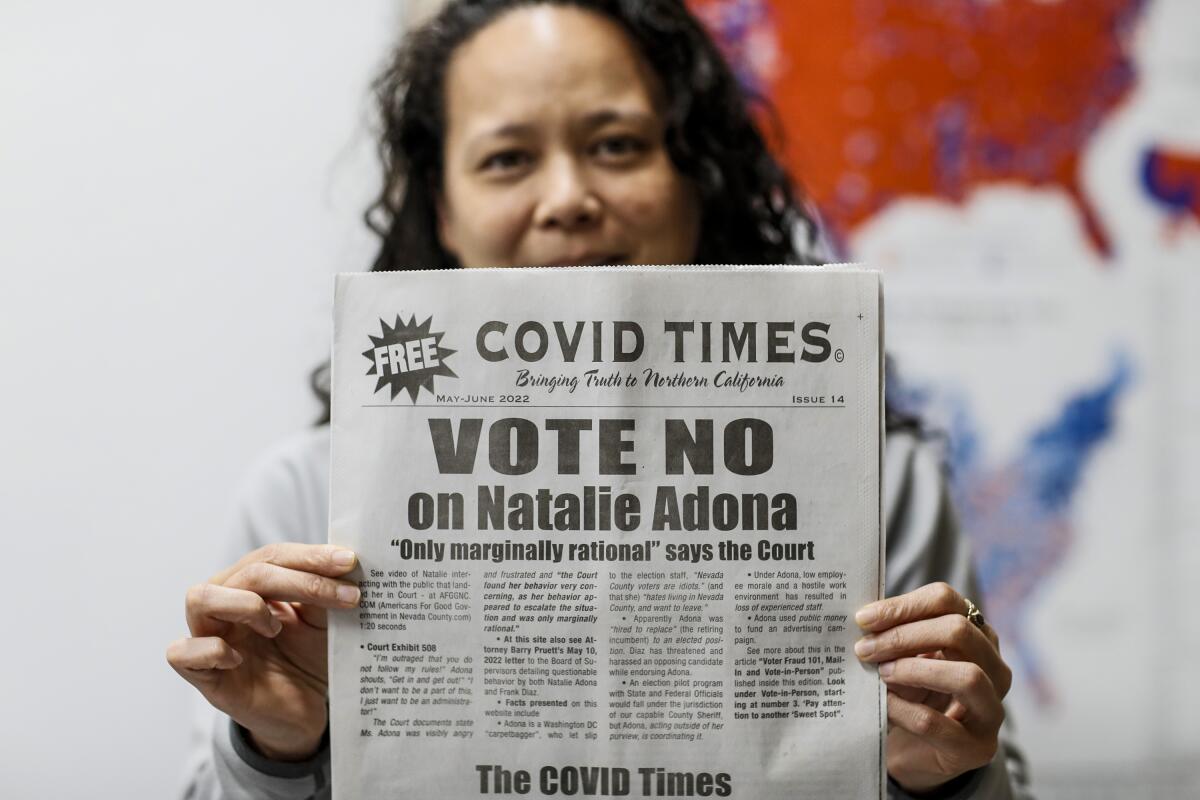

In Nevada County, a race for a county office has turned vicious, with claims of voter fraud and harassment of election workers.

Economy was a spokesman and advisor for the campaign to recall Newsom. The special statewide election last September, in which voters overwhelmingly chose to keep Newsom in office, cost state and local governments more than $200 million.

In Nevada County, the involvement of Economy — a conservative radio host who lives nine hours south in the Coachella Valley — has baffled local officials, who say the recount is a waste of time and resources and is nothing more than a thinly veiled attempt to sow doubt in the elections process.

“I can only think of this as being a process that’s disruptive to the whole county, and it’s about trying to further erode trust in our office,” said Gregory Diaz, the current Nevada County clerk-recorder and registrar of voters, who is retiring.

In California, any voter can request a recount, even if an election is not close, as long as the requester pays for it.

The Nevada County Board of Supervisors will have to appoint someone outside the clerk-registrar’s office — likely a registrar from another county — to oversee the recount, which is expected to begin this week, Diaz said.

The typically mundane race for clerk-recorder in the small Sierra Nevada foothills county this year got a heavy dose of the conspiracy-laden chaos former President Trump and his supporters have injected into politics around the nation.

The specter of Trump’s lie that the 2020 election was stolen loomed large.

Adona, the assistant clerk-recorder and registrar, ran against two opponents who publicly questioned the integrity of the voting process, echoing the rabid distrust in elections that Trump has fomented.

One of her opponents, Paul Gilbert, a self-described “citizen auditor,” said he personally inspected local 2020 election results and voting rolls and found evidence of fraud — claims the county disputes.

Gilbert told The Times he believed Trump won and that election officials should be allowed to crack open and inspect voting machines because they could have cellphone modems hidden inside that collect information for nefarious actors.

That is, of course, the kind of right-wing conspiracy theory about the security of voting machines that elections officials across the country have spent two years trying to debunk.

Gilbert got 9% of the vote.

Adona’s other opponent, Jason Tedder — a Navy veteran endorsed by the local Republican Party — said on his campaign website that sheriff’s deputies needed to be present each time ballots were collected at drop-off locations.

Ballots, he said, should be transported to the elections office in deputy vehicles and “tracked in real time” using GPS.

Tedder won 23% of the vote.

Adona, on the other hand, called the 2020 election legitimate. She drew the ire of detractors who called her “a carpetbagger” in election mailers — a label that some elected officials called a racist slur against an Asian American woman running for office in a mostly white county.

Adona also had to get a restraining order after anti-maskers — who were trying to recall the entire Nevada County Board of Supervisors — forced their way into her workplace.

Adona, a native of Vallejo, Calif., with 14 years of experience on elections, moved to Nevada County in 2019 to take the assistant clerk-recorder/registrar job.

Economy said he had “doubts about the process” in which she won.

“You have an unknown who came into a community and all of a sudden swamps everybody in an election? It’s just not passing the smell test,” Economy said.

In a July 4 letter to the county registrar, Economy said he was requesting the recount on behalf of Tedder, who came in a distant second place.

Tedder did not respond to calls and emails seeking comment.

Economy said he had been in contact with him “for several months,” because Tedder “had concerns and red flags.”

In red California, anti-mask recall effort fizzles and a candidate harassed by election deniers wins

A candidate for local office who was harassed by election deniers and anti-mask activists wins her race for county registrar of voters.

Kim Nalder, director of the Project for an Informed Electorate at Sacramento State University, said that, historically, recounts have been done only when votes are extremely close, when there truly is a chance it could go either way.

When a recount is requested in a landslide victory, she said, it’s most likely “a bad-faith effort to undermine the legitimacy of elections” and “to further this narrative that there’s widespread corruption among election officials.”

Recount requests, she said, are becoming much more frequent.

Because of Trump, Nalder said, “we still have almost half the country that has doubts about elections now, and that’s heartbreaking for democracy.

“We can’t go on like this endlessly into the future. We won’t have a democracy.”

In his request for a recount, Economy asked for the names, job responsibilities and wages of all poll workers — the types of workers who have faced so much harassment in recent years that California lawmakers are considering legislation that would treat them with the same caution as domestic violence victims by letting them keep their home addresses hidden from public records.

Economy also asked to be provided with all mail-in ballot envelopes that were sent in, along with voters’ on-file signatures used to verify their votes.

He said he made that request because he believes mail-in ballots lead to cheating — the false claim Trump has repeatedly made.

Diaz said much of the information that Economy requested will not be provided.

He said the manual recount process is slow and thorough. Four people will read, tally and verbally confirm each vote.

Diaz estimates that about 1,000 ballots can be counted each day. In a letter to Economy, Diaz demanded payment of about $10,000 before the recount can begin and about $1,800 each day.

“I want to charge him for every staple, every paper clip,” Diaz said. “It’s a frivolous request.”

Diaz sent Economy’s letter requesting the recount to local media outlets, angering Economy, who called that a threat to “people who are wanting to actively engage in democracy.”

“He came on the phone screaming at me because I let the media know and said, ‘How dare you?’ ” Diaz said. “I said, ‘How dare you?’ I don’t take that crap.”

“My bosses are the people,” he added. “If there’s going to be a recount for a contest with a 14,000-vote difference, I’m going to let my constituents know. If there’s going to be a recount with a difference of five votes, I’m going to let my constituents know.”

Adona, meanwhile, said she is just scratching her head over the whole thing.

“My first thought was — ‘why?’ ” she said.

“I can’t help but think there must be some reason other than wanting to change the outcome. That’s what’s concerning to me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.