‘My body, my choice’: How vaccine foes co-opted an abortion rights rallying cry

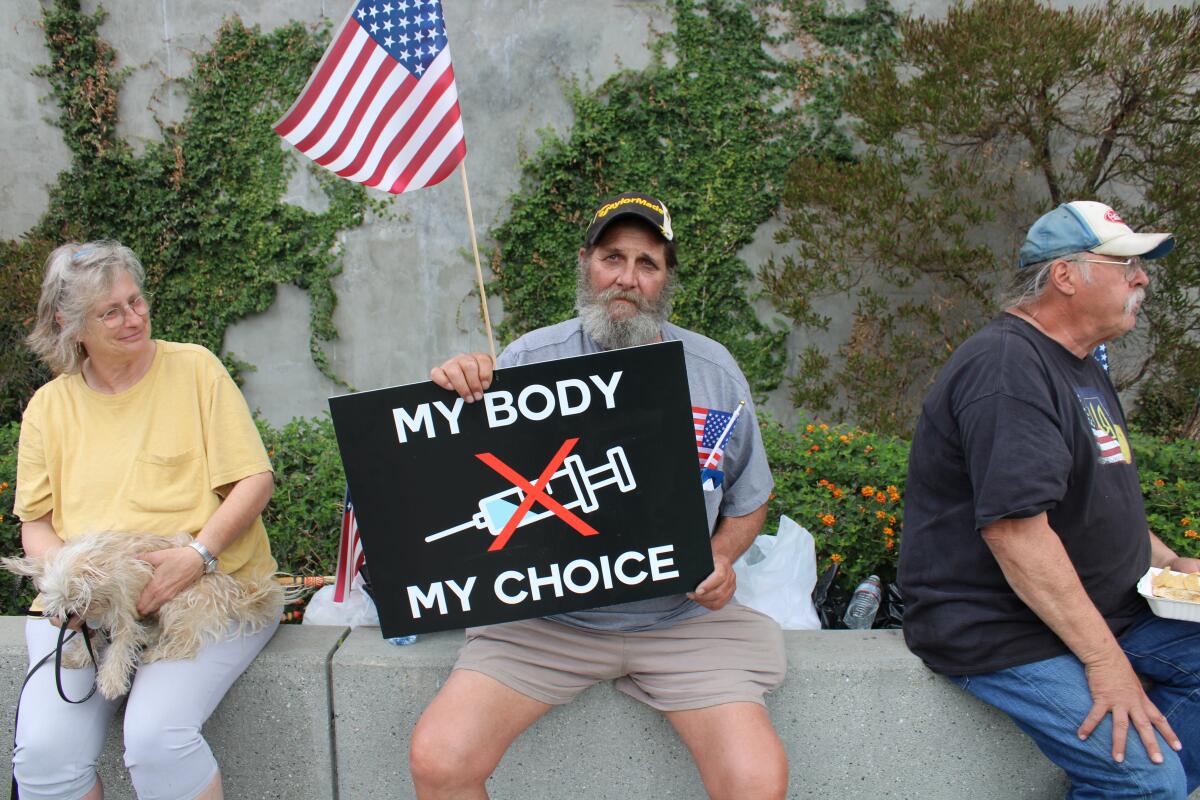

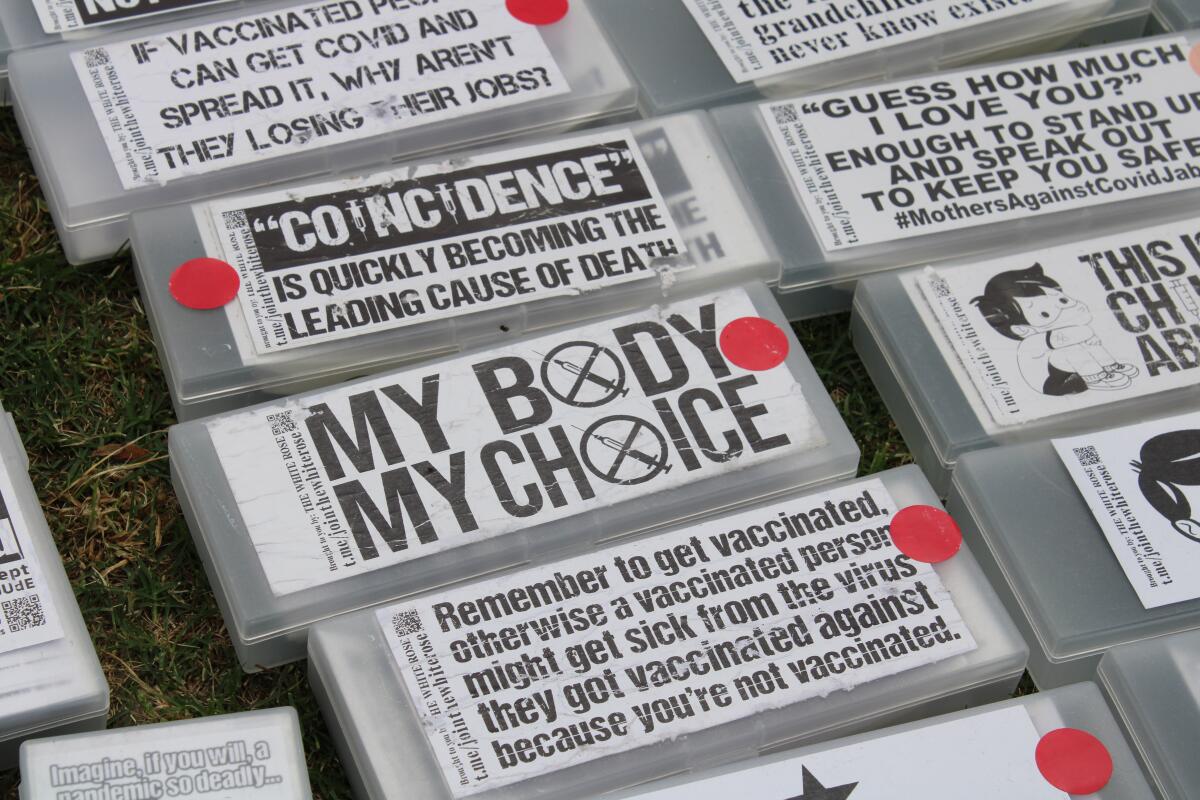

In the shadow of Los Angeles’ Art Deco City Hall, musicians jammed, kids got their faces painted, and families picnicked. Amid the festivity, people waved flags, sported T-shirts and sold buttons emblazoned with a familiar slogan: “My body, my choice.”

But this wasn’t an abortion rights rally, and it wasn’t a protest against the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling that gutted Roe vs. Wade. It was the “Defeat the Mandates” rally, a jubilant April gathering of antivaccine activists to protest the few remaining COVID-19 guidelines, such as mask mandates on mass transit and vaccination requirements for healthcare workers.

Similar scenes have played out across the country. Armed with the language of the abortion rights movement, antivaccine forces have converged with right-leaning causes to protest pandemic precautions.

They’re succeeding. Vaccine opponents have appropriated “My body, my choice,” a slogan that has been linked to reproductive rights for nearly half a century, to fight mask and vaccination mandates across the country — including in California, where lawmakers vowed to adopt the toughest vaccination requirements.

As the antivaccine contingent has notched successes, the abortion rights movement has taken hit after hit, culminating in the June 24 Supreme Court decision that ended the federal constitutional right to abortion. The ruling leaves it up to states to decide, and as many as 26 are expected to ban or severely limit abortion in the coming months.

Now that antivaccination groups have laid claim to “My body, my choice,” abortion rights groups are distancing themselves from it — marking a stunning annexation of political messaging.

“It’s a really savvy co-option of reproductive rights and the movement’s framing of the issue,” said Lisa Ikemoto, a law professor at the UC Davis Feminist Research Institute. “It strengthens the meaning of ‘choice’ in the antivaccine space and detracts from the meaning of that word in the reproductive rights space.”

Part of California’s anti-vaccine movement has expanded its reach during the pandemic. Now it is focused on new COVID-19 vaccines, and working with others to sow government mistrust.

Framing the decision to vaccinate as a personal one obscures its public health consequences, Ikemoto said, because vaccines are used to protect not just one person but a community, by stopping the spread of a disease to those who can’t protect themselves.

Celinda Lake, a Democratic strategist and pollster based in Washington, D.C., said “My body, my choice” is no longer polling well with Democrats because they associate it with antivaccination sentiment.

“What’s really unique about this is that you don’t usually see one side’s base adopting the message of the other side’s base — and succeeding,” she said. “That’s what makes this so fascinating.”

Jodi Hicks, president of Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California, acknowledged that the appropriation of abortion rights terminology has worked against the movement.

“In this moment, to co-opt that messaging and distract from the work that we’re doing and using it to spread misinformation is frustrating, and it’s disappointing,” Hicks said.

She said the reproductive rights movement was already gravitating away from the phrase. Even where abortion is legal, she said, some women can’t “choose” to get one because of financial or other barriers. The movement is now focusing more heavily on access to healthcare, using catchphrases such as “Bans off our bodies” and “Say abortion,” Hicks said.

Vaccination hasn’t always been this political, said Jennifer Reich, a sociology professor at the University of Colorado in Denver who has written a book about why parents refuse to vaccinate their kids. Opposition to vaccines grew in the 1980s among parents concerned about school requirements. Those parents said they didn’t have enough information about vaccines’ potential harmful effects, but it wasn’t a partisan issue at the time, Reich said.

The issue exploded onto the political scene after a measles outbreak tied to Disneyland sickened at least 140 people in 2014 and 2015. When California lawmakers moved to prohibit parents from claiming personal belief exemptions for required childhood vaccines, opponents organized around the idea of “medical choice” and “medical freedom.” Those opponents spanned the political spectrum, Reich said.

Then came COVID-19. The Trump administration politicized the pandemic from the outset, starting with decrying masks and stay-at-home orders. Republican leaders and white evangelicals implemented that strategy, Reich said, arguing against vaccination mandates when vaccines were still theoretical — scaring followers with rhetoric about the loss of personal choice and images of vaccination “passports.”

They gained traction despite an obvious inconsistency: Often, the same people who oppose vaccine requirements — arguing that it’s a matter of choice — are against abortion rights.

“What’s really changed is that in the last two or so years, it’s become highly partisan,” Reich said.

Joshua Coleman leads V Is for Vaccine, a group that opposes vaccination mandates. He said he deploys the phrase strategically depending on what state he’s working in.

“In a state or a city that is more pro-life, they’re not going to connect with that messaging; they don’t believe in full bodily autonomy,” Coleman said.

But in blue states like California, he takes the “My body, my choice” rhetoric where he thinks it will be effective, like the annual Women’s March, where he says he can sometimes get feminists to consider his perspective.

Perception of the word “choice” has changed over time, said Alyssa Wulf, a cognitive linguist based in Oakland. The word now evokes an image of an isolated decision that doesn’t affect the broader community, she said, and can frame an abortion seeker as self-centered and a vaccine rejecter as an individual making a personal health choice.

Beyond linguistics, antivaccination activists are playing politics, intentionally trolling abortion rights groups by using their words against them, Wulf said. “I really believe there’s a little bit of an ‘F you’ in that,” Wulf said. “ ‘We’re going to take your phrase.’”

Tom Blodget, a retired Spanish-language instructor from Chico, sported a “My body, my choice” shirt — with a cartoon syringe — at the Defeat the Mandates rally in Los Angeles. It was “an ironic thing,” he said, meant to expose what he sees as the hypocrisy of Democrats who support both abortion and vaccination mandates. Blodget said he opposes abortion and believes that COVID-19 vaccines are not immunizations but a form of gene therapy — which is not true.

A 22-year-old woman and an abortion doctor from California played key roles in the legal fight that led to Roe vs. Wade, now struck down.

For Blodget, and many other antivaccination activists, there is no inconsistency in this position. Abortion is not a personal health decision akin to getting a shot, they say — it is simply murder.

“Women say they can have an abortion because it’s their body,” Blodget said. “If that’s a valid thing for a lot of people, why should I have to take an injection of some concoction?”

About a week later and nearly 400 miles to the north, in Sacramento, state lawmakers heard testimony on bills about abortion and COVID-19 vaccines. Two protests, one against abortion and one against vaccination mandates, converged. Truckers from the “People’s Convoy” — a group that opposes pandemic mandates and had been touring the country with its message of “medical freedom” — testified against a bill that would stop police from investigating miscarriages as murders. Other antiabortion activists lined up to oppose a bill that would update reporting requirements to the state’s vaccination registry.

“My body, my choice” was ubiquitous: Kids petting police horses in front of the Capitol wore T-shirts with the slogan, and truckers toted signs.

At the time, two tough legislative proposals to mandate COVID-19 vaccinations for schoolchildren and most workers had already been shelved without a vote. One controversial proposal remained: a bill to allow children 12 and older to get COVID-19 vaccines without parental consent.

Lawmakers have since watered down the measure, raising the minimum age to 15, and it awaits crucial votes. They have shifted their attention to the latest political earthquake: abortion.

This story was produced by KHN (Kaiser Health News), one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation).

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.