Persevering through pandemic hardships, two members of the class of 2022 earn their diplomas

Beyond pandemic-related classroom instability and virtual instruction, college and university graduates from the class of 2022 had to overcome many obstacles.

This graduation season, thousands of Los Angeles-area graduates have proudly heard their names read aloud and walked the stage at commencement ceremonies that some universities have conducted for the first time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic more than two years ago.

But while graduation season tends to be a hopeful time, members of the class of 2022 are marking their triumph over months or years of virtual classes, financial hardships, illness and emotional challenges and setbacks.

Kelly Carland, who as UC Irvine’s special events coordinator has overseen many graduations, said this year’s commencement feels different. Students and faculty alike have looked toward in-person graduations with a mixture of hopefulness and anxiety that the next COVID-19 surge or some other unforeseen event could upstage the ceremonies.

“I know these students have dealt with so many challenges and had to overcome so much,” Carland said.

For two particular graduates this year, earning a diploma was not just a mark of finishing school, but a symbol of perseverance for them and their families.

A father’s last wish

Audrie Gomez’s father dedicated his life to providing for his family and to his long career as a maintenance worker at Cal State Northridge.

Audrie, 23, practically grew up on the campus, where her parents met. Her father, who worked there for nearly two decades, was nicknamed “Go-Go Gomez,” a tribute to his speediness and work ethic. His co-workers in maintenance were like Audrie’s uncles.

Her parents, both born in the United States and raised in Mexico, did everything in their power to send their three children to private schools and urged them to go to college.

Audrie Gomez, their middle child, graduated from high school when she was 17, spent one year at Pierce College, then left for the prestigious Parsons School of Design in New York City. But living in Lower Manhattan was expensive, she didn’t fit in with her wealthier peers, and Parsons’ business-like culture made her feel as if she had taken a 9-to-5 job.

One day while grabbing groceries at Whole Foods and feeling overwhelmed, she called her father.

“I was like, ‘Dad, I don’t want to be here anymore.’” Her father responded, “Go home, take care and we’ll talk tomorrow.”

She made her way back to her apartment, lugged her groceries upstairs and logged on to her computer. In the time it had taken her to get home, her father had called Cal State Northridge’s admissions department, and an email accepting her for the fall semester was sitting in her inbox.

“That was the kind of dad he was,” Gomez said. “He never said ‘no’ to me. I don’t mean that in an ‘I-got-everything-I-want’ kind of way, but he always made it work.”

At Cal State Northridge, Gomez joined a large cohort of first-generation college students, who account for 60% of the student body, according to the university’s fall 2021 enrollment figures. Initially she majored in journalism with an emphasis in public relations. She dreamed of working at Capitol Records and managing PR for famous bands.

Attending classes on the same campus where her dad worked was fun. She recalled her father and his co-workers often zipping by in their golf carts, yelling out “Good morning” or asking why she was late to class.

When the pandemic struck, Gomez found herself taking most classes from her bedroom. After the first few months of lockdown, Robert Gomez, working then as a staff plumber, was called back to campus at least once a week as an essential worker.

As the safety steward for his union, he also played a large role in keeping his colleagues from contracting COVID-19, said Jason Wang, Gomez’s supervisor.

“He made sure everyone got home with their faculties intact and really looked out for everyone,” Wang said. “He cared deeply about the campus and the students.”

As Gomez continued his work keeping facilities running on campus, virtual classes were difficult for Audrie. One semester, the stress of COVID-19 took a heavy hit on her grades.

Then, two weeks before the start of her senior year, her father was diagnosed with aggressive stage 4 stomach cancer. His dream was to make it to the spring graduation ceremony, but on March 30, midway through his daughter’s final semester, Robert Gomez died at home.

Amid the tragedy, Audrie Gomez found the energy to make it through the final two months of her senior year.

She looked to her mother, who gave her inspiration to keep moving, and thought of her father’s nickname. Anytime she felt anxious or as though her world was ending, she would think, “You’re a Gomez, you just have to go, like ‘Go-Go Gomez.’”

On graduation day, May 22, relatives filled her house, showering her with congratulations and questions about the future. As Gomez stepped into her backyard the morning before the ceremony, one of the familiar white butterflies that she often watched, but never touched, was back. After a few flutters around the yard, it came close and landed on her nose. It felt as though her father was saying, “I’m here for you,” Gomez said.

When she got ready to leave the house for the ceremony, she felt as though she was leaving her father behind. But taking those hard steps forward meant getting to see her father’s last wish to the end.

“It meant everything to me, to be able to give him that, and give myself that,” Gomez said.

Winding path to graduation

For years, graduating from high school, let alone university, felt like a far-off goal for Andrew Norman.

On June 11, the 29-year-old walked in a commencement ceremony for the first time, after two battles with cancer and a winding path to graduation. He earned his bachelor’s degree in psychological science from UC Irvine.

“If you were to tell me four years ago that I would go to UCI and have graduated, I wouldn’t have believed you. There’s just no way,” Norman said.

Norman, who was raised in La Habra as the youngest of nine, recalled an early childhood of playing outdoor games and tussling with his siblings. That changed at age 8 when he was diagnosed with leukemia.

From then until he was 13, Norman was home-schooled, kept away from contact sports while his friends and siblings played outside. Treatments continued to keep the cancer at bay during his early teenage years.

As he entered public high school, he recalled experiencing “chemo brain,” a side effect from cancer treatment known to give patients mental cloudiness and memory problems. While its exact causes are unknown, according to the American Cancer Society, its symptoms can last years.

Norman had trouble with math and reading comprehension. By the end of his freshman year, he was failing most of his classes.

Feeling a nagging sense that his peers knew he was struggling, he took on the role of class clown, Norman recalled.

“Because everyone knew I was doing poorly in school, I felt like I had to bring something to the table,” Norman said. “And if it wasn’t my smarts, it would be making people laugh.”

After his sophomore year, he dropped out of high school altogether, receding into a world of 16-hour days playing video games like “World of Warcraft” or “Halo.” Two years later, he watched his friends graduate from high school as he cheered from the sidelines.

One day, when he was 18, Norman felt a distinct pain in his side. He looked at his mother and said, “It’s back.”

An emergency room visit and blood tests confirmed that the cancer had returned. This time around, he was determined to move quickly.

“My motto I took for that whole treatment was ‘Challenge accepted,’” Norman said.

He went after his cancer head-on, sitting for chemotherapy treatments that would last 24 hours at a time and spending long days driving back and forth to the hospital with his mother.

Patti Norman said that three-year period was a “turning point” for her son. While he battled cancer a second time, Andrew continued to receive treatments at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles alongside young kids.

“He was almost like a role model to them,” his mother said. “He was older and seeing what he had gone through at that age.”

After the cancer receded, Andrew Norman said he felt a “different outlook” on life. He earned his GED and began taking psychology classes at Fullerton College.

“I didn’t really care about money or status, it was just like, the whole reason I want to be here is to help people,” Norman said.

By spring 2020, he had graduated from community college, but the pandemic thwarted an in-person commencement. Instead, his fiancee, Jessica Jaramillo, planned a miniature ceremony, inviting friends and family and delivering a commencement speech herself.

Afterward, he transferred to UC Irvine and spent much of his time in virtual classes that he attended from his parents’ garage, which had been converted into a studio apartment, while his fiancee, a fifth-grade teacher with L.A. Unified, taught classes from the same room.

Norman imagined that graduation would feel like being a college football player waiting to be drafted to the NFL and having that magical moment when you hear your name called.

“I’ve worked so hard for it and I’ve wanted it for so long,” Norman said.

Now, Norman has finally had his NFL draft moment. During the commencement ceremony for UC Irvine’s School of Social Ecology he sat between the neat rows of undergraduates clad in black robes, blue-and-gold stoles shining under the lights of the school’s basketball arena.

As he rose to walk, his eyes were fixed on the stage, undistracted by a cellphone screen or name-calling card. He walked slowly across the stage and, grinning, pumped his fist in the air a couple of times before heading down the stairs to resume his spot among the new graduates.

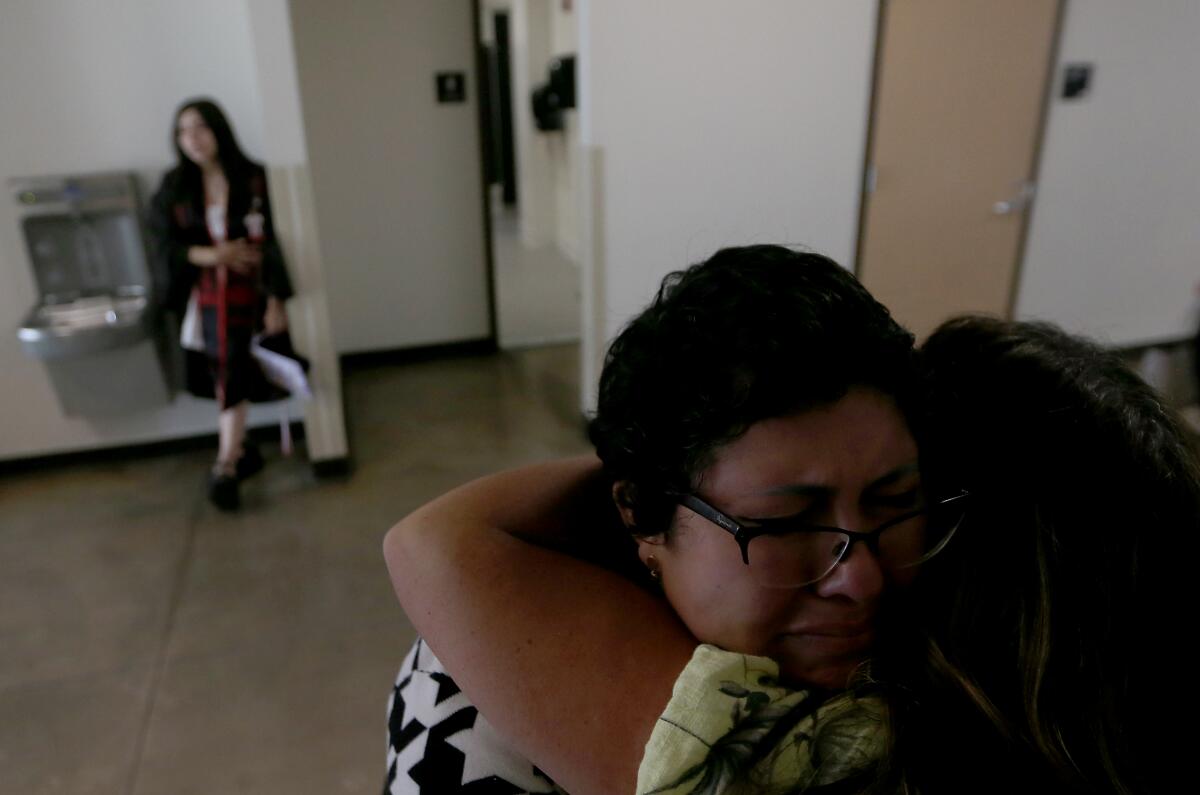

After the ceremony, he left the arena and embraced his mom, best friend, sisters and fiancee.

“We did it,” Norman said, hugging his mother. Patti Norman smiled at him, her eyes glassy.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.