A computer model predicts who will become homeless in L.A. Then these workers step in

When her phone rang in February, Mashawn Cross was skeptical of the gentle voice offering help at the end of the line.

“You said you do what? And you’re with who?” the 52-year-old recalled saying.

Cross, who wasn’t working because of her ailing back and knees, was scraping by on roughly $200 a month in aid plus whatever she could make from recycling bottles and cans. Her gas and electric bills were chewing up her checks. She had been in and out of the emergency room, her doctor said she might have to get a colostomy bag, and depression was bedeviling her day by day.

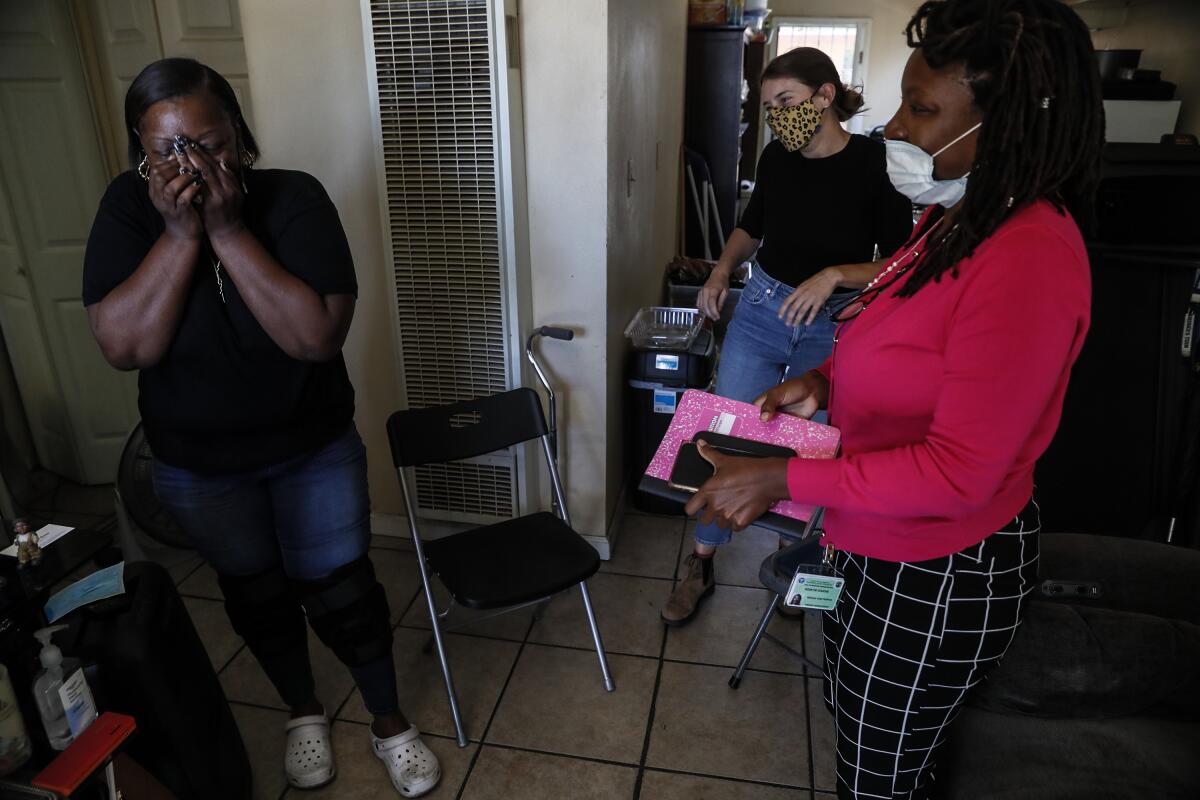

Kourtni Gouché listened and began to help. The L.A. County caseworker helped get household supplies for Cross so she could save money and cover her utility bills. She offered to get her a new bed to soothe her pained back. She began connecting Cross to programs to ease her depression and get her off cigarettes, something Cross has long wanted but struggled to do.

“I feel like I’ve got a friend right here,” Cross said, occasionally growing teary as she exalted the caseworker who had kept coming through for her. In her apartment in a South L.A. duplex, over the whir of a box fan, she abruptly remembered a question she had forgotten to ask Gouché during their regular talks.

“How did you get my name to start with?” Cross asked.

The answer is an unusual mobilization of data analysis to try to head off homelessness before it starts.

Cross is part of a rare effort by L.A. County to marry predictive modeling — a tool used to forecast events by tracking patterns in current and historical data — with the deeply personal work of homelessness prevention.

The county found Cross and scores of other people through a predictive tool developed by UCLA researchers, which pulls data from eight L.A. County agencies to help outreach workers focus their attention and assistance on people believed to be at gravest risk of losing their homes.

L.A. County has struggled to keep up with the number of people who become homeless annually, even as it steps up efforts to get people into housing. Figuring out whom to help is crucial because millions of residents seem vulnerable yet avoid homelessness, said Janey Rountree, founding executive director of the California Policy Lab at UCLA.

For the record:

10:49 p.m. June 12, 2022An earlier version of this story included an erroneous reference to the California Policy Lab as the California Policy Law.

“You would never have enough money to provide prevention for everyone who appears to be at risk,” Rountree said. “You really need another strategy to find out who’s actually going to become homeless if they don’t get immediate assistance.”

Researchers have found it surprisingly complicated to guess who will slide into homelessness and who will avoid it: In a report released three years ago, the California Policy Lab and the University of Chicago Poverty Lab said a decent prediction would require at least 50 factors — and that the best models would require “somewhere between 150 to 200.”

The predictive model now being used in L.A. County uses an algorithm that incorporates about 500 features, according to the UCLA team.

It pulls data from eight county agencies to pinpoint whom to assist, looking at a broad range of data in county systems: Who has landed in the emergency room. Who has been booked in jail. Who has suffered a psychiatric crisis that led to hospitalization. Who has gotten cash aid or food benefits — and who has listed a county office as their “home address” for such programs, an indicator that often means they were homeless at the time.

Rountree and her team discovered, when it began running such models to identify who was at highest risk, that “they were not the people enrolling in typical homeless prevention programs.” As of 2020, the UCLA team found that few of the people identified by its predictive modeling — under two dozen in two years — were getting services specifically meant to prevent homelessness under Measure H, an L.A. County sales tax approved by voters.

So the county decided to give them a call. In July, the newly formed Homeless Prevention Unit began to reach out to people deemed at highest risk by the predictive model, cold-calling residents like Cross. The UCLA analysis is done with data stripped of identifying details, which the county matches up with names and information to find possible clients.

The work is being undertaken in the Housing for Health division at the L.A. County Department of Health Services, which focuses on homeless and vulnerable patients. People in the program can get financial assistance and referrals to other services to help their overall health and housing retention. Single adults receive up to either $4,000 or $6,000 in assistance and families get an allocation depending on their size; the program is analyzing whether higher amounts make a difference in results.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

For Anthony Padilla Cordova, “it was perfect timing” when the call came in February. “I just didn’t know where I was going to go.”

Padilla, 29, had gotten out of state prison during the pandemic and was trying to stay off alcohol and drugs. He had finally gotten into rehab after getting arrested again because of his drinking and had moved from there into a sober living home, he said. But his life still felt precarious.

Many of his housemates, grappling with their own addictions, seemed “still stuck in the mindset of prison,” he said, and Padilla worried that if he lost his cool and fought with anyone, he would get kicked out. Padilla had started picking up work as a prep cook and dishwasher, but he hadn’t regained his driver’s license, which could mean hours on the bus to get to jobs as far as Irvine.

Fabian Barajas said he could help. The caseworker arranged to cover the costs of a breathalyzer that had to be installed and activated in a vehicle before Padilla could legally drive again. He got gift cards to defray day-to-day expenses such as groceries. He got him clothing and shoes to wear to work.

And “if I feel like I lost hope ... I’ve got Fabian I can call,” Padilla said.

Case managers work with each participant for four months, although they can extend that period for up to two months more if needed. As Padilla nears the end of the four-month program, he is now living in his own studio in MacArthur Park. He has stayed sober. He has his license again. And he has enough money saved up for a down payment on a car, Barajas said.

“Things are looking good — as long as you can stay consistent and sober,” Barajas told him as they met on a recent Tuesday.

Padilla reflected on the help he had gotten from the county and other programs. “If I didn’t have any of these resources,” he said, “I’d probably be homeless,”

Roughly 150 people have gone through or are now participating in the L.A. County program. It kicked off with $3 million in funding — half from Measure H, half from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation — and quickly garnered nearly $14 million in federal money under the American Rescue Plan, which will allow the program to carry through 2024, said Dana Vanderford, associate director of homelessness prevention. Its staff, once “a small and mighty team of seven,” will soon expand to 28, including 16 case managers, Vanderford said.

So far, roughly 90% of participants have retained their housing while in the program, Vanderford said. Rountree and her team are still assessing how such results compare with similar people who didn’t take part in the program, which will help determine if it was successful.

But based on past patterns and analysis, it is estimated that the first 54 people who participated in the program would have had a 33% risk of becoming homeless if the program did not exist and “the world were exactly the same” as when the analysis was done, Rountree said.

Still, “the world likely did change. That is why we will need to perform the full causal study,” she said.

Cross might seem, at first glance, like a surprising candidate for homelessness prevention. She has a housing voucher for her South L.A. unit. She isn’t fighting off an eviction or rent increase. But Cross has been homeless before — and without the help of Gouché and the program, she worries about the choices she would have to make between food and the electric bill.

“If she didn’t come along, I’d be sitting here saying, ‘Do I need to do this, or do I need to do this?’ ” Cross said. Now “I don’t have to stress if I’m going to get enough recycling this month.”

In the front room of her home, seated near a television stand decorated with elephant figurines meant to bring good luck, picture postcards from a trip to Catalina Island and a Bible opened to the Book of Psalms, she and Gouché talked through her next steps.

They discussed getting her a new bed and pillows to ease her back pain; the anxiety that Cross said was “nothing to play with”; her uneasiness with the many pills she had been prescribed, which she feared could leave her with another addiction.

Cross also wanted to quit smoking, saying that it was costing her money that she couldn’t afford. Gouché offered to get her phone numbers for smoking cessation programs, as well as additional resources that would help her with mental health and substance use issues.

Cross nodded. “Everything can be tried at least once,” she said. “If it works, I’ll keep going.”

Anger and depression had sent her back to cigarettes before, she said.

Gouché said, “The great part is your awareness — you just kind of said it — that that’s essentially how you cope with difficult situations.”

The programs could help build on that awareness and help her find other ways to cope, the caseworker said.

“You’re on the right path for sure,” she told Cross.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.