Column: Cops, not books? This town’s library may become a police station

McFARLAND, Calif. — When I visited this small Central Valley town on a recent Friday afternoon, the most happening place by far was the public library.

Teens sped around on their bikes in the ample parking lot, then went inside to peruse the bookshelves. Classical music — Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Tchaikovsky‘s “1812 Overture,” a couple of Bach harpsichord jams — blasted from someone’s Spotify. A couple of adults browsed the Spanish-language section. Tykes did crafts with branch supervisor Frank Cervantes; others worked on a Snoopy puzzle. Restless preteens bounced from computers to couches to chatting with one another like hipsters at the Coachella festival checking out different musical acts.

Outside, McFarland, population 14,000, was quiet. Inside the Clara M. Jackson Branch Library, it was a rager — literally, because the patrons were also mad.

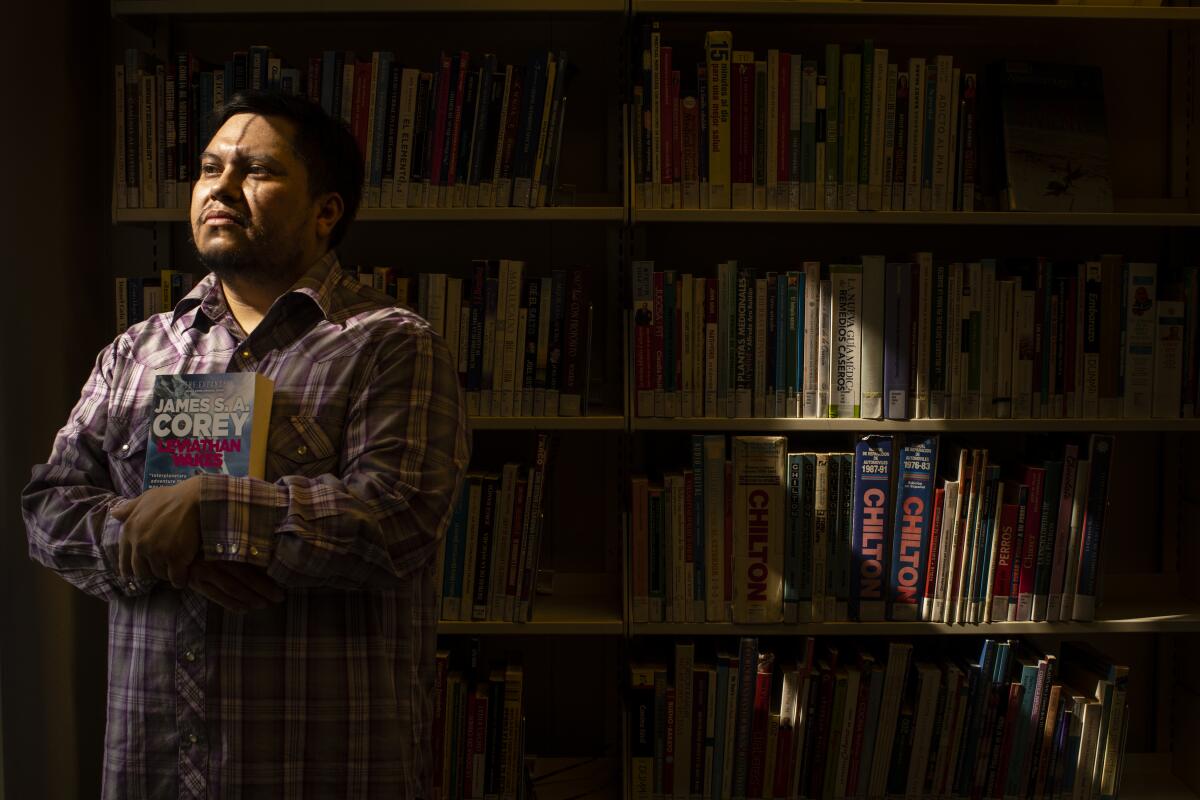

The city’s sole library is open only Thursdays and Fridays from noon to six, because that’s all Kern County — one of the most underfunded county library systems in California — can afford. It reopened in February after being shuttered since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cervantes, 35, said the pent-up demand was so great that “as soon as I unlocked the doors, so many people came in that they nearly knocked me down.”

But not even three months into its relaunch, the adults who run McFarland want to stop the library fun.

“It does provide some service, but sometimes you have to judge what’s most important,” McFarland City Manager Kenny Williams told me over the phone. He wants Kern County, which owns the library building, to let him turn it into the headquarters for McFarland’s Police Department — where he happens to be the chief.

“We would use that building 24/7,” he said, while swearing he had no conflict of interest. “When it comes to the library and public safety and comparing the use of the library building, [residents] recognize we have an issue with crime.”

Williams has the support of the McFarland City Council members, who wrote in a March letter to Kern County Chief General Services Officer Geoffrey Hill that there was only “minimal opposition” to the idea.

They forgot to talk to the people who actually use the library.

Analuz Hernandez and Yazmine Olivera, both 11, were there hanging out when I visited.

“We’re surrounded by a bunch of land!” Analuz said, referring to the acres upon acres of cotton fields and almond groves that make up McFarland’s biggest industry. “They can’t build something new on all that land?”

Yazmine, meanwhile, suggested a different location for the police headquarters. “They should go to the east part,” she said. “There’s more emergencies on the other side of here.”

“It should be open every day,” said Analuz’s brother, 8-year-old Francisco Hernandez Jr. “If this place isn’t open, then I’d have to be home. And that would be boring.”

Cervantes didn’t want to give too many opinions, partly because he had a bunch of kids to look after. But he did emphasize the importance of having a library in a small town like McFarland. He himself grew up in the even smaller agricultural community of Mettler, an hour away. His hometown had no library, but his mom was able to take him to libraries in bigger cities.

“It was the difference,” he quietly said, “between a bright future and the futures that some of my peers had.”

McFarland’s library controversy is starting to draw national attention in the literary world as yet another case of education being tossed aside.

But opponents are going to have a hard time trying to convince city officials to go against Williams, whom they see as a savior of sorts for the poor, overwhelmingly Latino town.

When he became police chief in February of last year, he admits to have been “astounded” at the issues before him.

Crime was exploding in McFarland, which was caught in the crossfire on the unofficial border between California’s Norteño and Sureño gangs.

A former city manager went missing for months in 2019 before authorities found his body in a car at the bottom of the Kern River. A previous police chief pleaded no contest in 2020 to using city funds to pay an officer to help renovate his home.

The Police Department had a reputation as a job of last resort for officers with misconduct records elsewhere. It was technically operational only from noon to midnight. Its headquarters down the street from the library are so small — shared locker room for men and women, one bathroom, sensitive evidence stored in a trailer — that Williams uses a noise machine so no one can overhear his conversations.

“It has been one struggle after another,” he said.

Williams has restored order to the point that the City Council appointed him city manager earlier this year. The Police Department is now on duty 24 hours a day and is hiring. A couple of weeks ago, Williams led a successful annexation of farmland that would nearly double the city’s size and allow it to capitalize on the continued migration of Californians to Kern County.

That’s why, he said, a new police headquarters is necessary. He doesn’t have the funds for a new building — which is where the Clara M. Jackson branch comes in.

“I like the library,” Williams said. “I think it’s a beautiful place to congregate. But it’s not being used enough.” When I asked if he would reconsider his takeover bid if it was open more days, he laughed.

“If it opens five days a week,” the chief-city manager said, “they’re doing it as a method so the McFarland Police Department doesn’t get the building.”

The City Council has said there will be a new library in an undisclosed location, open three days a week instead of two. Williams vows that a room currently used for story time will be a base for new Police Activities League and Explorer programs.

“You want to get impressionable youth between the hours of 2:30 and 6 and engage them,” Williams said, not appreciating the irony that the library already does that, during those hours.

Kern County Library spokesperson Jasmin LoBasso said her bosses haven’t heard anything from McFarland or county officials about what’s next. She criticized what she described as shortsightedness.

“Minimizing a library down to merely a facility that checks out books misses the point of what a library is,” she said.

If the city boots the library from its current location, “I do not know what the recourse would be,” she added. “And the need in McFarland is absolutely there.”

Back at the library, the few adults there were furious but resigned to the library’s demise.

In one quiet corner, Bertha Cuate went through school lessons with 7-year-old Nicolas Maldonado. The retired college professor tutors children at small library branches across southern Kern County.

“They learn to love to read and study here,” she said. “Denying them this would be a tragedy.”

Angie Maldonado showed up to pick up her son. The lifelong McFarland resident remembered the excitement when the library opened in 1994.

“We have nothing else here for kids,” said the 42-year-old. “We have no theater. You take this out, kids either stay home bored or go out on the streets.”

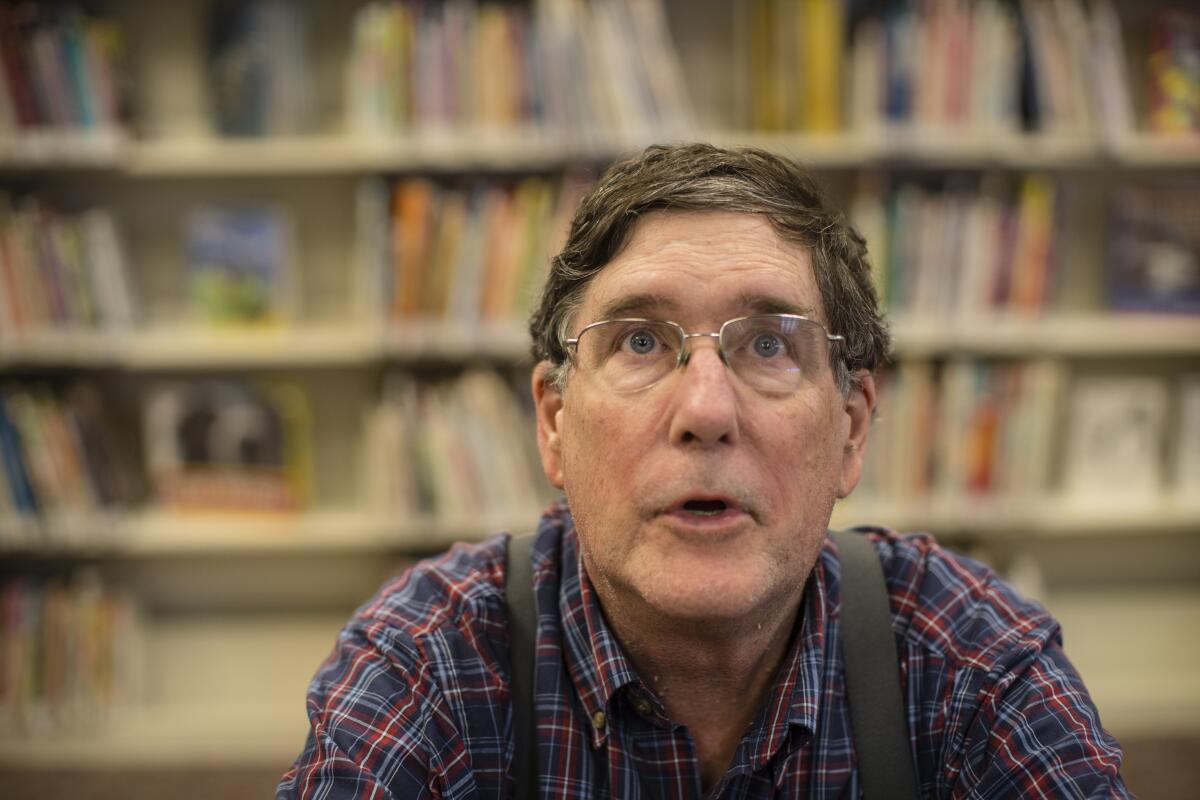

Phil Corr looked on with a smile as kids swirled around him. He’s the pastor at a church down the street and president of Friends of the McFarland Library.

“It’s an injustice to go after a vulnerable place,” said Corr, 66, the author of three books. “It’s logically and morally wrong. The police do need a larger place, and this building is ideally located. But it’s also ideally located for kids.”

Recently, he invited Williams to tour the library.

“Kenny saw a meeting room and said, ‘That’s where we can fit the library.’”

The pastor shook his head. “That?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.