Gaping digital divide among L.A. students is a civil rights issue, Supt. Carvalho says

Los Angeles school officials on Tuesday announced a $50-million effort to provide adequate internet to all families in the nation’s second-largest school system — the latest try at closing a persistent digital divide that has limited learning for students whose families can’t afford to pay for high-speed Wi-Fi access.

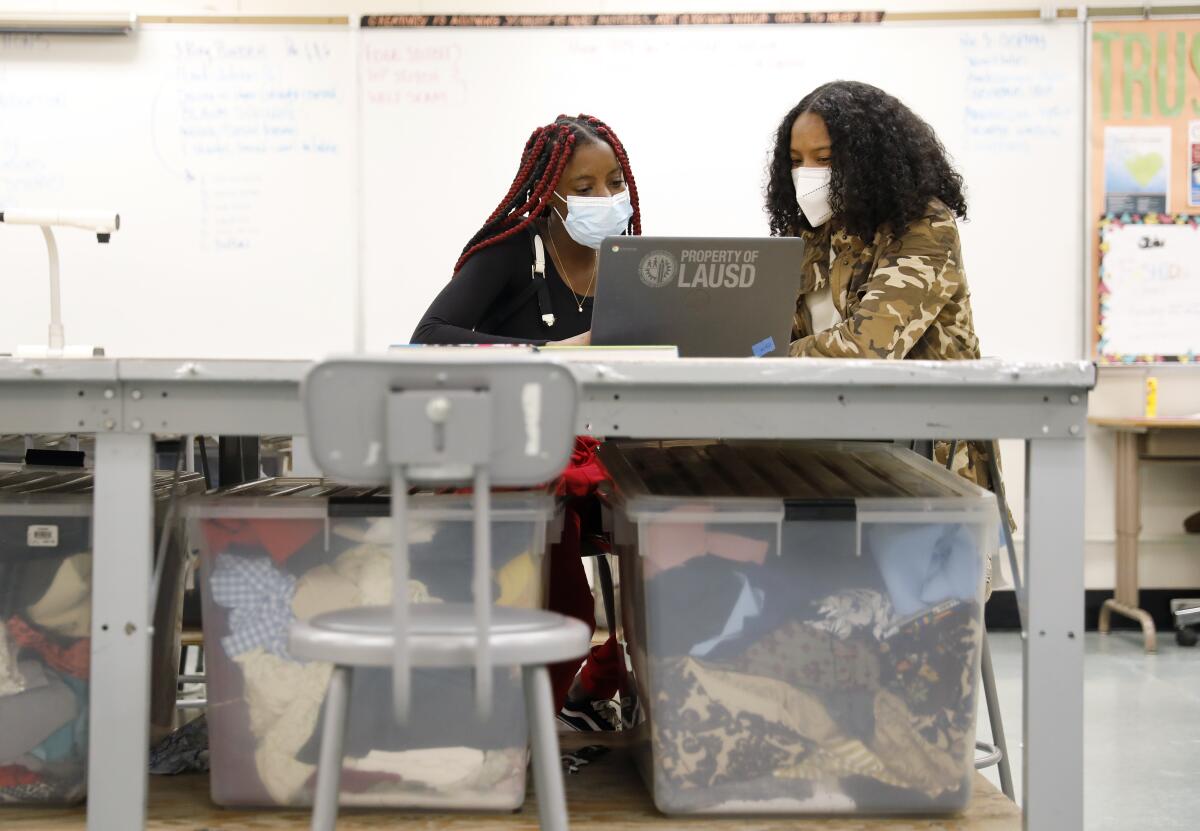

L.A. Unified estimates that about 20% of students — about 90,000 children — either still lack broadband service or don’t have enough bandwidth to meet academic needs — despite an initial emergency rush at the onset of distance learning two years ago to remedy the problem. The new initiative is targeted to reach all of them for one year using short-term federal funding to cover about 96% of the cost. It looks as though federal resources also will be available for a second year, Supt. Alberto Carvalho said in a kickoff ceremony at Bell High School.

The school system will offer access both to connect families and to demonstrate the necessity of this connection to federal and state officials — with the hope that permanent funding would be provided.

“Connectivity and universal ubiquitous access to digital content anytime anywhere, whether in school, in the community, in the park or the public library, is a civil right that must be delivered to our generation,” Carvalho said.

A separate district effort, also announced Tuesday, would provide students with a computer they could keep at home. About 60,000 students would benefit in the initial stage, officials said. Home computers are as necessary as textbooks, said L.A. school board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin, who supports the project.

The internet-access initiative, which has been in the planning and piloting phase for more than a year, received a formal launch in a low-income neighborhood that has exemplified both the challenges faced by families and some past success in district efforts to help them.

In the pandemic’s latest hit on education, the number of L.A. Unified students who have been chronically absent this school year has doubled.

When the pandemic led to the shutdown of campuses in March 2020, the first few months were especially difficult for Andrea Maciel, a Bell High ninth-grader. Her mother lost work and could no longer afford to pay for internet service, which made schoolwork hard to keep up with even though the school had sent a computer home with her.

“I struggled with it,” Andrea said. “I had to go to some libraries or had to go to one of my neighbor’s house. She was, like, nice enough to let me borrow her Wi-Fi and I was able to do my work.”

Nearly 1 in 5 low-income households in a recent survey reported going without internet for extensive periods, citing cost as the main reason for disconnecting.

Compared with many schools, Bell High distributed internet hot spots to students relatively quickly, and that worked for Andrea, but not for everyone across the vast school system of about 450,000 students. The hot spots had limited bandwidth, and different brands of hot spots worked better in some areas than others. The hot spots were almost useless in a few areas.

Santiago Juarez, now a Bell High ninth-grader, had trouble staying online for his middle school classes.

“Sometimes the Wi-Fi would shut off because there was too many people using it at one time,” Santiago said. “And it would just like shut off and it wouldn’t work for like a couple of hours.”

His family switched to a more effective provider.

“They had to pay more, but at the end of the day it was worth it because we were able to join the classes and do our work,” he said.

Providers offered discounts early in the pandemic, but these offers expired or provided only limited bandwidth or weren’t available in all areas. Parents with limited English skills sometimes had difficulty accessing these offers, and some families could not afford the service even with discounts.

In the current project, L.A. Unified has negotiated bulk discounted rates with AT&T and Charter Communications. Between them, the two providers should essentially be able to cover the entire L.A. Unified geography. Depending on the locale and bandwidth needs, L.A. Unified will pay about $15 to $65 per month per household. Most families have a cable hookup already and would plug into a provided digital box. But installation is also available when necessary, a cost the district will pick up, which could range up to about $300, said district Chief Information Officer Soheil Katal.

During remote learning, ninth-grader Ethan Ortega, then in middle school, had problems with bandwidth. His brother also needed Wi-Fi for school and his parents needed to be online for their work.

“Most of the time, a lot of people would be using the Wi-Fi,” Ethan said. “And because of that I would have a lot of trouble, especially with my schoolwork. We didn’t even have a solution for it. Because our internet provider was already like the best we could get.”

Los Angeles Unified must now make up for the lost schooling among its most vulnerable students

Independent research indicates that more people in California have a high-speed connection than ever — nearly 91% of its households have high-speed internet access, according to recent statewide survey results released by USC and the California Emerging Technology Fund.

Still, 16% of low-income residents are unconnected and 10% depend on smartphones, which provide an inferior connection for such tasks as schoolwork or attending class online.

California has the highest number of people living in poverty of any state, despite having the fifth-largest economy in the world. Income is a key determinant in whether a household has internet access, the USC report noted: Twenty-nine percent of households earning less than $40,000 a year have no internet connection or have access only through a smartphone.

The digital divide is both an urban and a rural issue: Nineteen percent of L.A. County and 20% of Central Valley households either have no connection or rely on smartphones. Nearly a quarter of Latinos are unconnected or restricted to smartphones, compared with 5% of white people. Digital inequity is greatest among Latinos who speak only Spanish — 25% have no connection and 10% rely on smartphones.

The divide came into acute focus during remote learning, when having an internet connection was the only way to access live instruction.

Before, during and post-pandemic, “access to the internet is a transformational tool,” said school board member Monica Garcia. “It’s all wrapped up in: Can we create a permanent solution for every home to have a tool that’s powerful for learning?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.