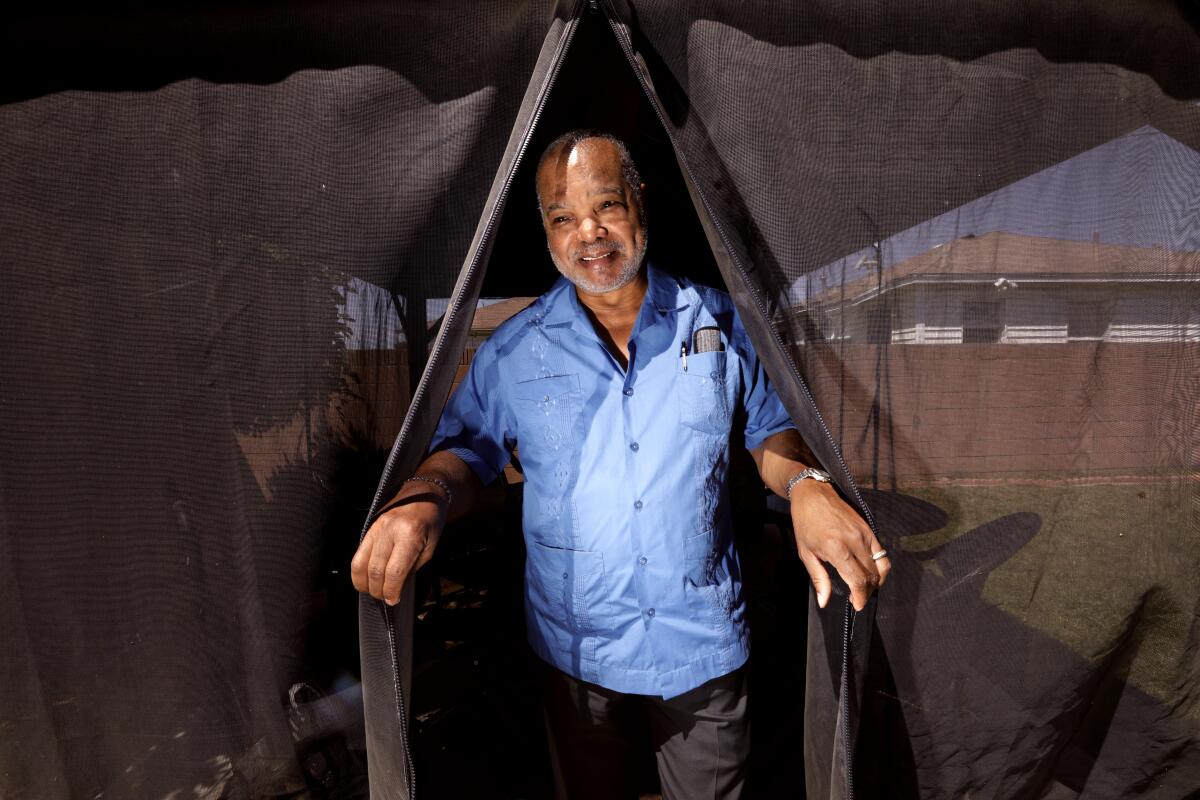

Can you be a NIMBY and a Christian? Ex-Motown singer struggles with a new homeless shelter

The Bible was always Larry S. Buford’s guiding light, but it put the one-time Motown singer-songwriter in a dilemma, when he found himself defending his South Los Angeles neighborhood from encroaching development.

Buford became increasingly alarmed over the span of two decades, as he watched the single-family homes on his tranquil block of Avalon Boulevard replaced by multi-story apartment buildings with insufficient parking.

The apartment buildings were for people who are poor or homeless or aged or mentally ill. And the deeply religious 68-year-old, who has lived in Willowbrook for a quarter century, was in a quandary: His personal values were at odds with his concern for his neighborhood.

And then he found himself in conflict with a spiritual brother: the Rev. Andy Bales, head of the Union Rescue Mission, the downtown L.A. homeless shelter that vows to “embrace people with the compassion of Christ.”

It would be a test for Buford, who was drawn to Motown not just because he was born in Detroit, but because, he said, he viewed it as an all-inclusive genre, one that advanced his own yearning for a diverse and peaceful world.

A test for a man who loved his neighborhood, which is about 10 miles south of downtown L.A., and who’s particularly fond of a Bible verse that urges us all to “bring the homeless poor into your house.”

::

Buford signed with Motown in 1984, the day after singer-songwriter Marvin Gaye was shot to death by his own father. He worked for four years under the wing of Gwen Gordy Fuqua — music mogul Berry Gordy Jr.’s sister — and attended get-togethers at her Beverly Hills mansion and other spots with the likes of Ray Charles, Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder.

After MCA bought Motown in 1988 and, in his view, stopped supporting its artists, Buford left the label without having a breakout hit. But he continued his craft as his own publisher. For more than a decade, he struggled over one song that had a title, “Can’t Quiet My Soul,” roots in Motown and unfinished lyrics striving for a universal theme of anti-violence.

That came when 26 people, mostly children, were killed in the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting in 2012. The massacre shocked the nation and released Buford from his writer’s block.

“When President Obama said, ‘Our hearts are broken today,’ it just flowed from there,” Buford said.

“Can’t rest for the suffering, can’t rest,” he wrote. “For children dying, children dying. I cannot quiet my soul.”

If you haven’t heard the ode to children who died by gun violence, don’t worry. Buford recorded the soulful song, but it was never released on a record label.

Buford moved to Los Angeles from his native Detroit in the 1980s. His stretch of Avalon Boulevard was one of those well-traveled arterial streets that is also lined on both sides by single-family homes.

Despite being divided by four traffic lanes, it used to be the kind of neighborhood where the guy across the street with the mobile barbeque pit would occasionally put on a feast for anyone who showed up.

“It was something you look forward to,” Buford said.

He worked as an office manager with a variety of firms from sales to bio-tech. And he settled into a dual role: as author of books with a spiritual bent and local reporter, publishing pieces about South Los Angeles in the L.A. Sentinel and other publications.

He calls his latest volume, Book to the Future, a faith-based account of how what we do today will affect tomorrow. It weaves together themes of eroding allegiance to the American flag and to the Bible, warning, “The more we continue to lower God’s standards as set forth in the Bible, the more we fall into immorality.”

He also occasionally emailed other journalists to vent over the encroachment on his block of big-box, government-financed residences for seniors and homeless people.

That focus began around 2000, when a 42-unit home for seniors rose across the street from Buford’s house. In 2012, the man with the barbeque pit sold his property. A Community of Friends, a nonprofit that builds and operates apartments for people with mental illness, announced plans to construct the 55-unit Avalon Apartments on the land.

Buford got involved with a neighborhood group that unsuccessfully fought that project. He reported on the protest for the L.A. Watts Times, taking a decidedly NIMBY — not in my backyard — approach.

“In a neighborhood fraught with vagrancy and loitering,” he wrote, “where policing is more reactive than proactive, there is even concern about the safety of the seniors and children who will be walking past the complex to go shopping or to school.”

The project was built anyway.

Eight years later, Buford’s protective instinct was aroused again when he learned that Union Rescue Mission, the venerable Skid Row homeless services institution, was planning to build a family shelter on the corner of 132nd Street.

The 86-unit building would fill the last open parcel on what was once a block of single-family homes, leaving only the Greater Pearl of Faith Baptist Church sandwiched between the shelter and the subsidized apartment building.

“How much can one community take?” Buford asked, venting his frustration in a 2020 email to The Times. “This unincorporated neighborhood already has a weak infrastructure as we pointed out to them. There was no impact study on how it would affect us.”

This time Buford took the lead, confronting Bales, the Union Rescue Mission president and CEO, at a 2020 community meeting that he said he had learned about only through the grapevine.

“As we mentioned to Andy, we are all for housing the homeless, but at least we should have been given the courtesy of an advance notification,” he wrote to The Times. “The site will make traffic and parking even more congested here at 132nd and Avalon.”

::

That meeting was the beginning of a dialogue that continued from the 2020 groundbreaking for Angeles House to preparations for its grand opening in April. Buford pressed Bales with his concerns, the main one being the exemption from parking requirements that homeless housing projects receive based on the premise that few of their tenants own cars.

In an email exchange with Bales in March, Buford questioned that premise.

“Can you tell me what the capacity for available parking space will be for the Avalon Interim Housing project?” he asked.

“I believe 67, Larry,” Bales replied. “Should be more than sufficient for our staff and few guests who will have cars.”

Buford quickly shot back.

“Unfortunately, that’s what we were told about the other property two doors down from yours,” he wrote. “Our concern is that your tenants will also have friends and relatives visiting, and the parking will spill out onto Avalon Blvd, making bad matters worse. ... Now people are parking in the alley; speeding with no precaution; and there is no enforcement. It’s a hazardous situation.”

“We are known for enforcing,” Bales replied. “We likely will join you in making sure all neighbors are respectful.”

The fact that Bales listened to him convinced Buford he was not dealing with a “car salesman” who would be out of the picture as soon as the deal closed.

“I think he is someone who could go with the long haul and he would be a great partner working with us,” he said.

Buford said he also felt the pull of empathy “born out of my association with Chrysalis,” the downtown homeless services agency where he once worked.

“I’ve always had a concern once my eyes were open to the plight of the homeless,” Buford said.

He also was impressed that the project was completed in just over two years and without using a dollar of taxpayer money.

Buford attended the April 14 grand opening — as a supporter.

On a tour, he responded to the cheerfulness of the building’s interior, with large common spaces on every floor, private conference rooms, health and dental clinics, a large chapel and amenities such as a hair salon.

“My wife does crochet,” he said. “Maybe she can volunteer.”

In fact, Loreen Buford also was impressed with the grand opening and the crowd it drew. “It’s been a long time,” she said, “since we’ve seen so many white people in the neighborhood.”|

During the speeches, Buford applauded enthusiastically when Bales took the stage.

Bales gave a spirited rebuttal to the “harm reduction” philosophy, which he contends allows drugs to flow in government-supported housing. Programs based on harm reduction work to keep people as healthy as possible even if they are still using drugs and alcohol, for example, providing clean needles to stop the spread of disease. He also argued against rules that prohibit religious expression.

Then he read from Scripture.

“Is not this the fast that I choose: ... Is it not to share your bread with the hungry and bring the homeless poor into your house?”

Buford recognized the passage.

“Isaiah,” he whispered. “That’s one of my favorite verses.”

Afterward, when the two met face-to-face, Buford made some demands.

Could Bales use his influence to help him get speed bumps in the alley? And a crosswalk for the people in the apartment who jaywalk.

“With flashing lights,” Bales said.

“Flashing lights or something,” Buford said.

And there were other concerns.

“Give me a list,” Bales said. “Let’s all work on that together.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.